The Russian invasion of Ukraine presented a significant strategic challenge to the Chinese leadership. Yun Sun, director of the China Program at the Stimson Center in Washington, D.C., argued that Russian President Vladimir Putin successfully tricked China into creating an image that China supported the Russian invasion, even though Beijing neither anticipated nor endorsed the war. Evan Feigenbaum, vice president for studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, identifies Beijing’s three competing and contradictory objectives vis-a-vis the Russian-Ukrainian war: China’s strategic partnership with Russia, commitment to long-standing foreign policy principles of “territorial integrity” and “noninterference,” and a desire to minimize collateral damage from EU and U.S. sanctions.

After being caught off-guard, Beijing tried to square the impossible circle through a diplomatic campaign. Between February 24 and May 19, Beijing conducted 64 diplomatic meetings with foreign counterparts that discussed the ongoing war in Ukraine. This diplomatic campaign has two stages. The first stage focused on Western countries, with the aim to shape Western policy outcomes. On March 15, U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan met with Politburo member Yang Jiechi and reaffirmed the position of a unified NATO. After the March 15 Sullivan-Yang meeting, China’s diplomatic campaign shifted its target toward developing countries. Through both stages, Beijing emphasized three messages: blaming NATO for the war, calling for negotiations to stop the war, and protesting Western sanctions against Russia.

China’s first message blamed NATO expansion for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In more than half of its diplomatic meetings, China urged the West to “understand Russia’s legitimate security concerns” and “build a sustainable European security system through negotiation.” In describing the cause of the war in a video summit with U.S. President Joe Biden, Xi Jinping said “one hand cannot clap,” which blamed the United States and NATO for ignoring Russian concerns.

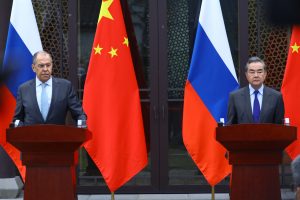

Even in a meeting with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Kuleba, Foreign Minister Wang Yi declared that “one country’s security should not be achieved by damaging another country, regional security should not be achieved through military bloc expansion.” As this quote suggests, Wang justified the Russian invasion and blamed Ukraine’s aspiration to join NATO for harming Russian security concerns and bringing invasion upon itself. In another meeting with Prime Minister of Pakistan Imran Khan, Wang claimed that “Ukraine should be the bridge between East and West rather than a pawn of great power competition.”

China’s second point was to protest anti-Russia sanctions after the war broke out. The Russian invasion sparked a unified response from Western countries. On the day of the invasion, the U.S., Canada, U.K., and many other countries implemented sanctions on Russian financial institutions and key oligarchs close to the Putin regime. The day after, the European Union rolled out a sanctions package against Russian leaders, financial institutions, and exports to Russia.

On February 26, the West pulled out its sanction trump card. The U.S., EU, U.K., Canada, France, Germany, and Italy announced a joint action to remove Russian banks from the SWIFT financial messaging system. On March 2, the EU decided to kick out seven major Russian institutions from SWIFT by March 12.

Following the SWIFT sanctions, China started to convey anti-sanction messages during diplomatic meetings. During a video summit with French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Xi said that sanctions would further aggravate the world economic crisis during the pandemic and “do not benefit anyone.” In a meeting with French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, Wang not only repeated Xi’s message but also criticized Western sanctions for obstructing international law and intensifying the conflict.

From the beginning of the war, China has upheld the principle that the war should end through negotiation. As Sun of the Stimson Center pointed out, this statement reflects Beijing’s desire to end the war as soon as possible. However, China also uses this talking point to criticize Western military aid to Ukraine. China bashed U.S. military aid to Ukraine as “adding oil to fire,” which obstructs the negotiation process.

During a phone call with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Xi said that the international community should “promote negotiation wholeheartedly,” which is a subtle criticism of Western countries that both promote negotiations and provide military aid to Ukraine. During the April 1 China-EU summit, Xi lectured that the international community should not “add oil to the fire and intensify the conflict.” In a meeting with his French counterpart, Wang criticized the West for “fanning the flame” to intensify the conflict through military aid and further declared that Western countries should not “promote no war while intensifying the war by sending high-tech weapons to Ukraine.”

China’s diplomatic campaign expressed such an intense pro-Russia sentiment that several social media users even cracked jokes, such as asking “Does Wang Yi work for Putin now?” However, China did not match its words with deeds. China’s top diplomat promised that Beijing is not deliberately circumventing sanctions on Russia. Chinese state banks also conformed to financial sanctions on Russia and restricted financing for purchasing Russian commodities.

Beijing also rejected accusations that China was considering providing military aid to Russia. During a phone call with Ukraine’s Kuleba on April 4, Wang said that China “will not add oil to fire.” While criticizing Western military aid to Ukraine, this message reassured Ukraine that Beijing would not provide military aid to Moscow. The compliance demonstrates that Chinese leadership understands the threats from the United States and European Union clearly. Beijing is unwilling to sacrifice its most important trading partners to support Putin’s war.

China’s objective, in fact, is not to support the Russian war effort. Instead, Beijing is using the Russia-Ukraine war to address its own strategic concerns and geopolitical challenges. The anti-U.S. and anti-NATO message aims to implicitly condemn a U.S.-led regional military alliance in the Indo-Pacific and warn Asian countries against bandwagoning with the United States.

During a meeting with Pakistan, China’s traditional regional ally, Wang warned that China “will not allow military bloc confrontation in Asia and small countries becoming tools of great power competition.” In a summit with President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, a U.S. treaty ally, Xi stated that “regional security could not be achieved through military alliance. China will join Philippine and other regional countries … to control regional security in our own hand.” Xi’s statement reflected China’s harsh criticism toward U.S.-led security structures in Asia and conveyed a strong “Asia for Asians” attitude.

During a meeting with Vietnamese Foreign Minister Bui Thanh Son, Wang Yi openly attacked Washington, saying that “the United States creates regional conflicts and undermines ASEAN-centrality by forcefully pushing its Indo-Pacific Strategy. We cannot allow the return of the Cold War mentality and the repeat of the Ukrainian tragedy in our region.”

China’s anti-sanctions rhetoric has two meanings. First, China fears that the economic consequences of the current sanctions might affect China. Wang called Spanish Foreign Minister José Manuel Albares and pleaded that “China is not a party of the (Ukrainian) crisis, so China does not want sanctions to affect itself.”

Second, China worries that the sanctions on Russia might establish a precedent among Western countries. Beijing fears that China might face such a united front of sanctions one day. That would undo the “reform and opening” of the past 40 years, create a tremendous economic crisis, and shake the foundation of the Chinese Communist Party’s legitimacy. In addition, Europe’s determination to go after the wealth and relatives of Russian ruling elites and Putin’s cronies worries China. Many Communist Party leaders hide their wealth and families overseas. Xi’s sister lives in Canada, and his own daughter, Xi Mingze, is reportedly living in the United States and studying at Harvard, where she received her undergraduate degree. Thus, by calling sanctions unlawful and creating an international anti-sanctions coalition, CCP leaders aim to put pressure on the West so they will not dare to use similar sanctions against China.

Finally, China’s rhetoric against military aid targets Taiwan. Arms sales to Taiwan have been causing China-U.S. tension since the 1982 Joint Communique, and it has become a greater problem in recent years. China uses the same phrase — “adding oil to flame” – to criticize U.S. military sales to Ukraine and Taiwan.

Beijing worries that the parallels being drawn between Ukraine and Taiwan might lead to more military sales to Taipei. In addition, the effectiveness of Western weapons in tipping the military balance favoring Ukraine certainly shocked China. Beijing fears that the West might act similarly and aid Taiwan heavily during a potential war. Thus, Beijing warns against U.S. plans to militarize Taiwan further.

Although Wang declared that “Sino-Russian friendship has no limitation and no ceiling,” the reality shows that the Beijing-Moscow partnership actually has quite a lot of limitations and a low ceiling. Beijing will not sacrifice its strategic interests for Moscow; it is only willing to lend moral and rhetorical support. Furthermore, China uses this moral support to push forward its own agenda. For the Chinese leadership, the Russian invasion is not just about Europe; Beijing wants to use the war to warn the United States and send messages to its neighbors. It is a classic case of “killing the chicken to scare the monkey,” except Beijing is using the “chicken” killed by Moscow to send warnings of its own.