The central role of Western military aid to Ukraine in its fight against Russia has highlighted military aid as a critical part of broader U.S. security cooperation efforts. Amid strategic competition with China, one might assume that Beijing would have a large military aid program as part of its own approach to winning friends and influence through military diplomacy, its somewhat analogous version of security cooperation. That might not be a safe assumption.

A new RAND report explores security cooperation by the United States, China, and Russia amidst strategic competition and finds that “the United States and its allies enjoy a significant competitive advantage.” As part of this new report, we researched and compiled the first comprehensive assessment of Chinese military aid.

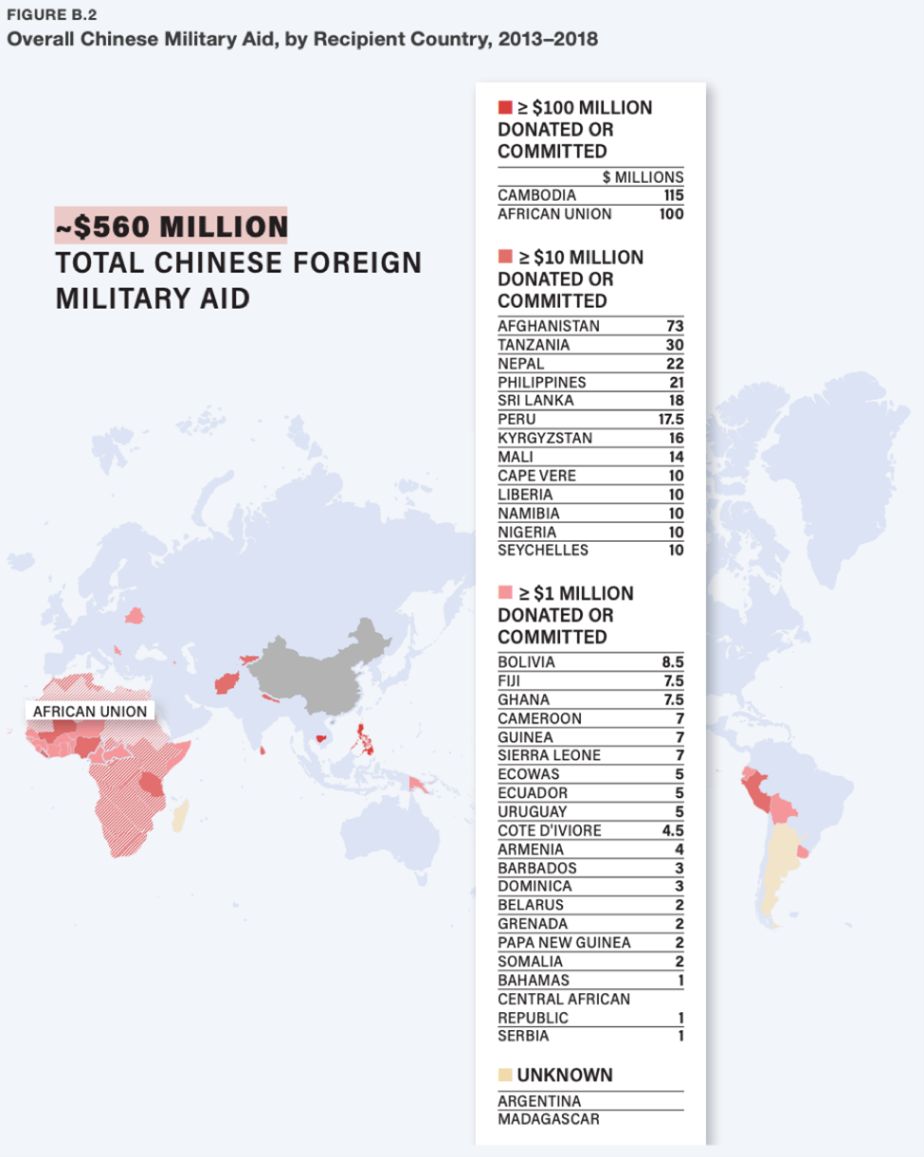

China’s $560 million total military aid during 2013-2018 pales in comparison to the U.S. total of over $35 billion over the same period, with U.S. military aid to the top five recipients in just the Indo-Pacific Command region totaling over $1 billion. Beijing’s total is also perhaps less than half of Russia’s total over the same timeframe. France and Germany each contributed almost $2 billion in 2017 alone. Put simply, China is not a world leader in military aid.

The report defined military aid as military equipment given to another country as a donation, not a sale or even a no-cost loan, and our data includes not just actual donations but also commitments. Though the time period covered for this report was 2013-2018, we have continued to watch Chinese military aid deliveries and commitments since that time and have not seen a dramatic departure from this pattern.

The top recipients of Chinese foreign military aid over the 2013-2018 period were Cambodia, with a reported $100 million pledged in 2016 ahead of elections for Prime Minister Hun Sen (plus more in 2018), and the African Union, with $100 million pledged in 2015 by Xi Jinping during his big United Nations speech. These reflect two different apparent motivations for Beijing. For Cambodia, Beijing likely sought to maintain its influence with the Cambodian government. For the African Union, Beijing was likely seeking to build its soft power in Africa. Another apparent motivation, though much less common, could be improving China’s own security via improving stability along its borders. This motivation could explain the $73 million China pledged to Afghanistan in 2016 for countering the Taliban.

The countries missing from the list of recipients of Chinese military largesse are equally interesting, though perhaps not surprising. We found no evidence that Beijing gave its only ally, North Korea, any military aid over 2013-2018, a period when bilateral relations were generally poor. We also did not identify any military aid to China’s top arms buyers of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Algeria, and others – why give when you can sell?

There is little known about Russia’s recent request for military aid from China, which apparently was rejected. Even if China was warm to the idea of helping Russia, it seems unlikely it would have actually provided “aid” for free – Moscow has plenty of things like energy resources and military hardware that Beijing could have asked for in return, even if it didn’t want to ask Russia for cash.

There are several important caveats to these numbers. First, the Chinese government has never released its own total, and very rarely actually confirms, much less provides a value for, its military aid publicly – the commitments to Cambodia and Afghanistan, for example, were announced by the recipient governments. This means it is possible our estimate understates Chinese totals, though it is difficult to imagine Beijing and recipients hiding sufficient enough donations to change our estimated total by an order of magnitude.

Second, our estimate includes both commitments and actual donations – and given Beijing’s track record on other aid pledges, it is quite possible that not all of these commitments will materialize.

Lastly, this is only the first attempt at a comprehensive count of Chinese military aid, and there is room for this research to be expanded and updated.

The Philippines is a good example of media hype obscuring the reality of limited Chinese security cooperation. Just like Beijing has not delivered on its 2016 economic promise of $24 billion to Manila during Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte’s early flirtation with China, a 2017 Chinese offer of a $500 million loan to buy Chinese military equipment has gone unused. Beijing did donate $21 million over 2013-2018, including $7 million worth of rifles and ammunition in 2017 for counterterrorism and $14 million worth of patrol boats in 2018. Since our research was completed, Beijing has continued sending military aid, including almost $12 million worth of “rescue and relief equipment” in January 2022. Yet this again pales in comparison to the $496 million of U.S. military aid to the Philippines over 2013-2018 (and $770 million over 2015-2020).

We identified several longstanding, and well known, issues that still may need to be resolved. Perhaps most importantly, legacy U.S. commitments dating to the War on Terror era and even earlier could be reconsidered as the Biden administration continues to focus on strategic competition with China and Russia, and Washington might also develop targeted programs for priority countries. The United States also could do better in coordinating with allies and partners – Japan, for example, has donated equipment to the Philippines and Indonesia, among others in Southeast Asia. Finally, such aid does not always have to be focused on warfighting capabilities, as it has been for Ukraine. As most countries in Asia hedge in the China-U.S. strategic competition, supporting peacetime priorities such as maritime domain awareness is also important and may be even more welcome by those capitals.

While the United States could do better, the report illustrates that it has dramatically outspent China in military aid around the world and this should offer significant advantages in the intensifying China-U.S. strategic competition.