The Diplomat author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners, and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Dr. Joseph Torigian – assistant professor at the School of International Service, American University and author of “Prestige, Manipulation, and Coercion: Elite Power Struggles in the Soviet Union and China After Stalin and Mao” (Yale 2022) – is the 327th in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.”

Explain the interplay of prestige, manipulation, and coercion in elite power struggles post-Stalin and Mao.

Political scientists have often characterized Leninist regimes as institutionalized systems of exchange – in other words, individuals compete for leadership by promising the most popular policy or patronage platform among some defined group. The conventional historiography of the post-Stalin and Mao transitions paints a similar picture: that “reformists” defeated “conservatives” or “radicals” in a political environment shaped by, albeit limited, inner-party democracy. But the new evidence we have about those eras suggest a very different story. Instead, the post-cult of personality power struggles in history’s two greatest Leninist regimes were instead shaped by the politics of personal prestige, historical antagonisms, backhanded political maneuvering, and violence.

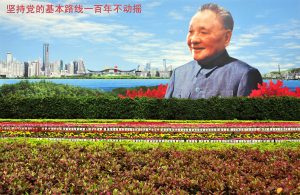

For example, we often see claims that Hua Guofeng, Mao’s initial successor, was a dogmatic figure who refused to rehabilitate the old revolutionaries who had suffered during the Cultural Revolution. Yet we now know that Hua supported the key early elements of reform and opening and sought joint control with his elder comrades. Hua’s greatest weakness was not an unpopular, “leftist” policy platform but a lack of revolutionary prestige compared to figures like Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun. And Deng, who allegedly wanted to “institutionalize” the party after the lessons of Mao’s strongman rule, manipulated party rules and relied heavily on a personal relationship with the People’s Liberation Army to slowly push Hua out of power.

Compare and contrast the dynamics of elite politics in Beijing and Moscow during the Cold War period.

In both cases, we saw a failure of collective leadership – both Nikita Khrushchev and Deng Xiaoping were able to seize dominance after the deaths of Stalin and Mao. To achieve those victories, Khrushchev and Deng relied on similar tools – the use of compromising material and historical antagonisms, the clever and tendentious interpretation of ambiguous rules, and courting the so-called power ministries the military and political police.

But those transitions had one key difference – in China, the old revolutionaries who had suffered during the Cultural Revolution returned to dominance, while Khrushchev pushed out his senior comrades like Viacheslav Molotov and Lazar Kaganovich. Those different outcomes occurred despite a similar political culture across the two systems that equated seniority with historic contributions to the revolution and regime. But Khrushchev emerged victorious because he obtained compromising material on his opponents, who had been sullied by their roles in the worst abuses of the Stalin era. And Khrushchev put that evidence in the hands of Marshal Georgii Zhukov, whose presentation of those crimes – as well as Zhukov’s control over the armed forces – proved fatal in a showdown with the old guard that occurred in 1957.

Analyze the failure of the Soviet Union and China to institutionalize politics in their own ruling parties.

That is a very interesting and important question. Many people within the party did indeed want real institutionalization precisely because the lessons of dictatorship were so strong in the years after Stalin and Mao died. Chen Yun, a very prominent elder during the 1980s, once asked Zhao Ziyang, the general secretary of the CCP, why no Politburo Standing Committee meetings were held. Zhao said that he was just a “secretary” and that Chen should ask Deng. Chen clearly wanted an opportunity to speak his mind, but Deng did not want to provide such opportunities. Even Xi Zhongxun, the father of Xi Jinping, remarked that it was necessary to prevent another strongman leader from acting like Mao (although Xi Zhongxun maintained a deep emotional commitment to the late chairman). Yet, strikingly, both Chen Yun and Xi Zhongxun always supported Deng’s authority within the party and never directly challenged him.

What explains this puzzling behavior? With regards to China, first, after the Cultural Revolution, the party had a phobia of the chaos that might occur if political contestation spun out of control. Second, the CCP had a long tradition of obeying the top leader. Third, the CCP always had a powerful taboo against factions. Fourth, Deng had the authority and prestige of a senior revolutionary. And fifth, Deng had a special relationship with the People’s Liberation Army. And, as I’ve written in the Journal of Cold War Studies, Khrushchev lacked Deng’s awesome power, but even Khrushchev was able to usurp collective leadership and only narrowly lost a leadership battle sparked by a group who felt a need to act first before Khrushchev purged them instead.

Identify the elements of Chinese and Russian communist elite politics of the Cold War era that underpin current political culture in Xi Jinping’s China and Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Xi Jinping and Deng Xiaoping have a great deal in common. Xi, like Deng did, believes that the party only works with a single “core” leader, and Xi occupies the same political system that functions on norms of deference. As leader, Xi also has special access to compromising material, interpretation of party rules, and the military and political police. But Xi lacks the awesome power of Deng, who was one of the titans of the revolution. And Xi, unlike Deng, is more involved in the day-to-day running of the party than Deng was.

Examine what the history of elite power struggles in Russia and China might portend for present-day elite power politics in Moscow and Beijing and assess implications for foreign policymakers in U.S., European, and Asian capitals.

One of the most important and perhaps surprising findings in the book is how little policy differences mattered. Unambiguously, Leninist systems are not personality contests. Leaders do not automatically lose because their policies are unpopular or because they are seen as incompetent – in all the cases studied for my book, the showdowns were inspired and resolved by other factors. Certainly, contestation over policies exists, but political competition is primarily among deputies or about convincing, not forcing, the leader to shift in another direction. And during moments of crisis, there is a “rally around the leader” effect because of a fear that power struggles may exacerbate the situation and threat regime stability. For countries that wish to compete with Russia and China, it will be difficult to affect change in those nations by attempting to trigger an elite revolt.