Many Asian labor-sending states developed their labor-export policy in the 1970s to exploit labor shortages in the Middle East. As contemporary Gulf states modernized their public and private domestic infrastructures, the Gulf temporary labor program became a vital source of economic assets (remittances, trade, migration industry) as well as feeding diplomatic conflicts, especially in the areas of labor and human rights, for Asian labor-sending states in the Global South.

Top Asian labor exporters to the Gulf, such as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and so on, have unrivaled sectoral dominance in construction, domestic work, health, and other semi-skilled professions. Yet, despite their continued sectoral labor dominance, smaller Asian labor-sending states — particularly Nepal — have also tried to compete in the Gulf labor sector, often with lax bilateral labor standards and migrant welfare protection systems that inevitably make their migrants vulnerable.

While global media and rights organizations have widely publicized the deaths of Nepali migrant workers in construction projects for Qatar’s hosting of the World Cup this year, little is known about the role of the Nepali state, particularly its domestic and foreign policy strategies toward the Gulf states and other powerful Asian migrant-sending states. This puzzle leaves unanswered inquiries: How can a small sending state like Nepal compete with traditional Asian sending states that appeared to have more relative bargaining power and migrant welfare protection in the Gulf? What is the future of Nepal in the Gulf, and what possible policy options can be considered to alleviate its weak position in the Gulf labor market?

In this article, we argue that the Nepali state’s potential to become a top regional labor supplier to the Gulf countries will depend on its domestic political investments on migration-development programs (i.e. migrant upskilling both at home and in the host countries) and how its transnational diplomatic actors approach and govern its interstate migration diplomacy strategies across the Gulf in the long run.

Gulf’s Sectoral Labor Market Competition

The Gulf region is the largest migrant destination in the Global South. In fact, the Gulf temporary labor program for migrant workers grew from 2 million in the early 1970s to 29 million in 2018 – meaning migrants account of 51 percent of the current total population of 56 million in the Gulf countries. With annual remittances exceeding $108 billion, Gulf countries have become a leading source of employment for millions of foreign migrants, making the Gulf region a highly diverse and competitive labor market destination for non-Western migrants, as well as sending states in Asia, Middle East, and more recently, Africa.

As the Gulf labor markets become more competitive to penetrate due to various domestic economic and policy factors (i.e. nationalization, Gulf labor bans, etc.), many Asian sending states have strategically targeted specific Gulf labor market sectors that have massive domestic labor shortages that cannot be easily replaced by local populations. Such a foreign policy strategy helped many Asian sending states dominate key Gulf labor market sectors over the past decades.

For example, South Asian migrants dominate Gulf labor markets, with 7.4 million Indians working in construction and services. Pakistan and Bangladesh targeted the construction and fishing industries. Most of the 2.1 million Filipinos in the Gulf work in domestic work, nursing, engineering, and other service-related fields. These labor-sending states dominate Gulf market sectors due to the “unique” competitiveness of their migrant workers (i.e., cheap labor, English-speaking capacities, similar religions, etc.). These labor-sending states’ political and institutional investments in domestic education and training for export to the Gulf and beyond have enabled them to compete, even during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As regional market competition for Gulf employment becomes higher, smaller sending states like Nepal often struggle to secure an adequate share, thus making them disadvantage in the host country labor market.

Nepal’s Sectoral Position and Dilemmas in the Gulf

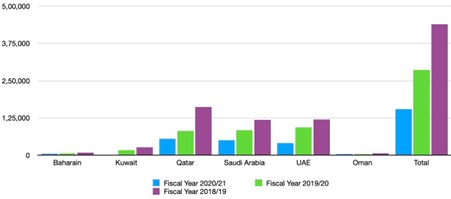

Over the past decades, Nepal has steadily positioned its migrant populations across the Gulf by deploying them in key strategic sectors, mostly in low-skilled jobs (i.e. security, construction, domestic work, and other service-related occupations). As Figure 1 highlights, migration outflow from Nepal (based on labor permits for the fiscal years 2018-19, 2019-20 and 2020-21) to the Gulf region illustrates an increasing trend over the past years.

Figure 1: Migration Outflow from Nepal to the GCC Corridor

Data from Nepal’s Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE)

Figure 1 suggests that the migration trend is getting back to normal, akin to the pre-COVID-19 era. However, the migration sector went through a series of challenges in past three years, drawing into question the effectiveness of Nepali migration governance both at home and abroad.

While Nepal is viewed as a small but increasingly competitive Asian sending state with a “big agenda” for Gulf labor market dominance, Nepali workers in the Gulf remain a small but expanding migrant population due to regular and irregular routes facilitated by migration brokers. In Qatar, thousands of Nepali migrant workers helped build 2022 World Cup infrastructure. Nepali domestic workers compete with Filipinos, Bangladeshis, Indonesians, Kenyans, and Ugandans for Gulf jobs. Others work in security, hospitality, cleaning, and other service-related jobs.

In fact, Nepal struggles to compete with traditional “big states” and institutionally places its nationals in the Gulf, unlike larger states. Gulf-based companies lack confidence in the industry training provided to prospective Nepali migrant workers, especially in construction. Raaj Snathe, managing director of Snathe Group, a leading training and upskilling provider in the Asia-Gulf migration corridor, acknowledged that “training centers in [labor-sending countries like Nepal] lack investment, are poorly managed, and lack the infrastructure, trainers, and expertise to deliver training to standards that lead to valued certification.” Gulf-based firms view Nepali workers as having “weak skill and training levels” and significant language barriers (i.e. Arabic and English). These conditions often affect not only the contractual terms and agreements of migrants, but also the Gulf-based company’s future recruitment of migrants.

Long-standing historical market segmentation of other foreign migrant workers in construction, domestic work, and hospitality, combined with their linguistic versatility in English and Arabic, have prevented the Nepali state and its migrant nationals from gaining a competitive advantage in the Gulf labor market. These labor market perceptions, combined with the small (yet growing) percentage of its migrant workforce in the Gulf, have reduced Nepal’s ability to leverage migrant populations in interstate negotiations with Gulf nations.

While Nepali migrant workers are preferred in construction and domestic work due to their low labor costs, competition from India and Pakistan prevents Nepal from gaining a larger economic share in Gulf labor markets. The limited presence of skilled Nepali migrants in major Gulf sectors, especially human resource management, which is dominated by Arabs, Pakistanis, Indians, and Filipinos, diminishes migrants’ ability to penetrate significant recruitment opportunities. This lack of market access puts pressure on the Nepali government and its citizens to shift market recruitment to Nepal. Recent migrant recruitment to Nepal has increased due to regional events (e.g., Qatar’s World Cup), but construction and domestic work employers in the Gulf region prefer non-Nepali migrants.

Diplomatic and Institutional Restraints

The Nepali state is structurally constrained in ensuring the labor rights and welfare of its migrant labor force. Nepal’s lack of legal assistance and appropriate welfare services (labor mediation, shelter units, institutional and staffing capacities within embassies/consulates) in the Gulf undermines its institutional power and capacity to guard its migrant population in the host country.

The Nepali government has pledged to strengthen labor protection for its nationals in the Gulf through bilateral cooperation with Gulf states, but greater political commitment and consistency are needed to end migrant precarity and exploitation in the Gulf and at home. While the Nepali government has sought bilateral labor cooperation with Gulf states, these documents offer migrant workers little or no labor protection. The lack of state protection and assistance for Nepali migrant workers may reflect diplomatic weakness.

While the Nepali government faces difficult internal and institutional challenges, it has actively promoted interstate dialogues, meetings, and bilateral negotiations with other Gulf countries to market Nepal’s current and future potential in trade and investment, agriculture, tourism, water, etc., as well as its migrant labor supply. But this only increases worries that the government sees Nepali immigrants as a negotiating chip. Does Nepal’s government estimate migration’s social costs? These contradictory national interests — economic versus social welfare — raise crucial questions about Nepal’s future political intention and vision, as well as its long-term foreign policy approach to Gulf states and labor-sending state competitors.

Future Gulf Strategy

Nepal’s weak bargaining position in the Gulf reflects its precarious position in world politics and affects its ability to enforce laws and institutions in host nations. Nepal’s weak position leaves the government with complicated domestic and foreign policy options, creating precarity among Nepali migrants in the Gulf.

While increasing migrant share and ensuring safe migration in the Gulf appears to be the top foreign policy challenge, the Nepali government can still take slow, incremental steps to improve labor market competitiveness domestically and potentially abroad. Nepal can invest in, reform, and align its domestic labor markets with regional or global standards (e.g. through training and certification programs) to create a more inclusive, open global market for Nepali migrant workers. The major sending states and their institutions have advanced interstate market engagements with Gulf states. TESDA of the Philippines has developed state-run upskilling, training, and certification programs and actively forged bilateral labor agreements and relations with Gulf countries to address critical migration issues (i.e., upskilling, training, certification) via consultative dialogue processes like the Abu Dhabi Dialogue and the Colombo Process).

Domestic institutions and state actors play an important role in closing “asymmetric information” gaps in the Nepal-Gulf migration corridor so the Nepali state can make more calculated, long-term foreign policy decisions. Foreign policy objectives must prioritize labor rights and welfare for migrant workers in the Gulf and beyond. As Gulf countries’ future of work agenda interests develop, Nepal must closely monitor not only the Gulf, but also how other large labor-sending states develop, monitor, and engage their domestic and foreign policy institutions to secure a significant market share in the Gulf labor markets.

These foreign policy calculations depend on Nepal’s future vision and how it positions current and future labor migration in its national government strategy. If labor migration is viewed as an evolving part of Nepal’s migration discourse, the state must develop in-house migration research units, strengthen domestic educational and training institutions, and link them with destination labor markets in the Gulf, Malaysia, and elsewhere. By developing a comprehensive foreign policy approach that takes into account Gulf countries’ (and sending state competitors’) evolving foreign policy interests, constraints, and tensions, the Nepali state could only create an orderly, safe, and competitive market niche for Nepali migrants over the long term.