These are turbulent times in Australia-China relations. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, senior leaders from both nations have been barely on speaking terms, amid a Chinese campaign of economic coercion designed to “punish” Australia after then-Prime Minister Scott Morrison called for a investigation into the origins of the coronavirus. Falling upon a relationship that was already strained by assertive Chinese actions in the South China Sea and elsewhere, this campaign marked the definitive end to an optimistic era in which Australian politicians and policymakers viewed China as central to Australia’s present and future prosperity, pushing relations into a more fraught, fearful register.

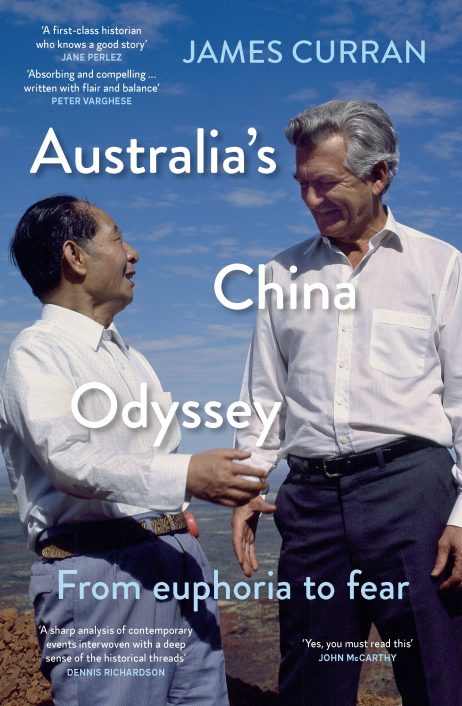

In his new book “Australia’s China Odyssey: From Euphoria to Fear,” released last week, James Curran shows that the current Australian fear about China is not new, and indeed, has co-existed with the excitement, at times bordering on jubilation, that attended the development of relations with Beijing since normalization in 1972.

Curran, a professor of modern history at Sydney University, spoke with The Diplomat about the complex mixture of euphoria and high anxiety that have accompanied that last half-century of relations, the Cold War echoes in Australia’s current China debate, and what might lie ahead for the country’s China policy.

In your book, you argue that the sharp deterioration of Australia’s relations with China “can only be fully understood and appreciated against the hopes, dreams, and aspirations” that successive Australian governments have had since the establishment of diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic in 1972. What were these hopes and aspirations, and what influence have they had on the current state of relations between Canberra and Beijing?

I think it is important to remember the breakneck speed at which Australian policy towards China changed in the early 1970s. Almost overnight – at the very same time as Canberra gave White Australia its burial rites and began to embrace multiculturalism as a new national orthodoxy – China, a country which had been the spectral demon in national security debates during the Cold War, now took on an altogether different character. The relationship with Beijing came to be the symbol of a new era in Australia’s outlook on the world. China became invested with a sense of euphoria and liberation: that Australia could chart a new foreign policy that did not necessarily look instinctively to its great and powerful friends in London and Washington. What you then had was a desire on both sides of politics to move quickly beyond the old fears and phobias about China.

Ideology, for a start, dropped through the foreign and defense policy trapdoor. Thus Fraser looked to use China in realpolitik terms as a counter to the USSR. Hawke worked to build economic and educational ties, and subsequent prime ministers, all the way to Abbott – and perhaps even Turnbull at the end of his period in office – put economic prosperity at the very heart of the China engagement story. What they did not do, however (save for a rather embarrassing lost in translation moment under Abbott) is invest in China the same kinds of aspirations that colored many American visions of China’s ultimate trajectory in that era. Australian leaders did not believe that greater economic liberalization would usher in greater political freedoms in China and perhaps even democracy. Australian assessments were never as altruistic or romantic as those in Washington. Senior U.S. policymakers only really gave that hope its quietus in 2017.

But as we know, that era of Australia-China engagement is long gone, and it won’t be coming back. It means that all the hopes and aspirations of an earlier era have been cast aside: this is hardly surprising given the rupture that Xi’s time in office represents in terms of Chinese assertion and bullying. But dealing with this new era is also leading to some distortions in both capitals.

The Chinese have forgotten the helping hand Australia gave it along the modernization path, including Australian support for China’s entry into international economic institutions. And if it is true that the Chinese believed they could peel Australia away from the U.S. alliance system in Asia, it only underlines their lack of understanding of the deep cultural and psychological forces which tighten Australia’s American embrace.

The Australian narrative of recent years also has its problems: not only have a slew of older epithets and slogans been ransacked from an older Cold War catalogue and newly deployed in the domestic debate, but in some quarters the conviction is that a succession of leaders were dazzled by the China market, “kowtowed” to Beijing, and in the process left Australia vulnerable in the face of a rising and more forward leaning China. But this is a fallacy: a major conclusion from my book is that this relationship has rarely been easy to manage, and that anxiety and angst has trailed closely in the slipstream of burgeoning trade and other ties.

You chronicle the development of China-Australia relations by examining how a succession of Australian prime ministers, from Whitlam to Albanese, have perceived China and Australia’s relationship with it. How important was the agency exercised by Australian leaders compared to more structural factors in the relationship, such as China’s meteoric economic growth from the 1990s?

I think the two were a mutually reinforcing dynamic – the leaders drove China policy as the economic opportunities began to expand, particularly in the 1980s and then into the 1990s and beyond. Whitlam set the tone – in some ways this was inevitable given the drama surrounding his 1971 visit and the stunning breakthrough it represented. The prime ministers have taken charge of the relationship – and I suppose that’s not really any different from how leaders took charge of the relationship with London at the height of empire and now of course with Washington: this is how our system works. Prime ministers gain their amour propre on the world stage.

But I would add that prime ministerial carriage of the China relationship did assume a flagship role in their broader management of the period of comprehensive engagement with Asia. Where we were with China, to some extent, became a test of our broader regional policy. Some believed it was possible to have a “special relationship” with China – it vied with Japan for Australian attention. So the leaders sought to set both the rhetorical tone for the relationship, and their visits of course became major manifestations or events in their own right of how Australia was progressing in bilateral ties. The tendency for the leader to be at the forefront was reinforced by Fraser’s 1976 visit in which he tried to engineer a quadrilateral pact (comprising China, Australia, the U.S., and Japan) to take on the USSR and then Hawke’s incredible long, late night discussions with the Chinese leadership – unparalleled at the time and since – underlined this prime ministerial pre-eminence.

My book is the first to cover these discussions in considerable detail, and in their proper context. Howard of course continued the trend: it was he who, along with Jiang Zemin, stabilized the relationship after the 1996 Taiwan Strait crisis. The prime ministers have had to do the repair jobs too – after the Tiananmen massacre, after 1996, and in 2009 after the so-called “annus horribilis” when one crisis piled on top of the other. Turnbull tried a reset of sorts before he left office but heard nothing back from Xi. We are now in a situation where, of course, the relationship continues to be frozen at leader level, so that dynamic is completely removed from the equation at the moment. The relationship, by and large, has been stripped down to one of commercial transaction.

You argue that Australian policymakers have often prided themselves on recognizing the “threat” posed by China earlier than more distant Western nations like its primary ally, the United States. What do you think explains this tendency? Is it just a case of geographic proximity, or does it say something more profound about how we perceive our place in the region and the world?

Undoubtedly the geopolitical anxiety stemming from longstanding concerns about being an isolated outpost at the edge of Asia is part of the reason – and a rising, bullish China has focused the strategic mind, there is no question about that. But at a practical level it is also about the fact that Australia made decisions on foreign interference and protecting critical infrastructure somewhat earlier than many others in the U.S. and U.K., for example, although a careful look at the chronology is needed there.

There is equally no doubt that the heroic narrative of Australia as the antipodean colossus astride the frontlines of a “new Cold War” – calling out and pushing back against Beijing, and gaining undreamt of accolades in Washington for doing so, has tapped something in the national psychology: the need to be seen and heard by the great and powerful friend; the desire to gain alliance kudos by showing our mettle in the face of coercion and the need too; and to make the case for American staying power in Asia.

There is equally no doubt that the heroic narrative of Australia as the antipodean colossus astride the frontlines of a “new Cold War” – calling out and pushing back against Beijing, and gaining undreamt of accolades in Washington for doing so, has tapped something in the national psychology: the need to be seen and heard by the great and powerful friend; the desire to gain alliance kudos by showing our mettle in the face of coercion and the need too; and to make the case for American staying power in Asia.

In essence, the bravado about being the model for standing up to China stems from a certain insecurity about the future of American resolve. But this approach, which does stem from a view about Australia “punching above its weight” in world affairs (dating back to Billy Hughes at Versailles and H.V. Evatt at San Francisco, among others) has had its limitations – and former prime minister Scott Morrison’s call for U.N.-style weapons inspectors going into China to investigate the source of the coronavirus pandemic is probably the standout example in recent times. It was, however, interesting to see a high ranking national security official quoted towards the end of the Morrison government saying that “Other countries are going to reach a conclusion – either Australia is offering a successful template for other nations in defying China’s coercion or we become an example of what not to do.” The jury, I think, is still out on this.

It’s still early days, but how do you assess the Albanese government’s approach to China? Is it a case of 2017 vintage policy in new, Labor-branded bottles, or do you think there has been, or could be, a significant change?

Early days indeed, but I think we now have a clear marker, or divide, between the first two months of the new government and its current approach. Australia’s fraught journey with China continues. The crisis brought about by the visit of U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan last week – and the brutal Chinese reaction to it – now appears to have interrupted moves on both the Australian and Chinese sides to at least begin talking to each other again. Of course, that cautious resumption of ministerial contact at the defense and foreign minister level with Beijing has not ushered in any reprieve from Chinese economic coercion. And two Australian citizens, Yang Hengjun and Cheng Lei, remain incarcerated in China.

Coming to office, Mr Albanese and his ministers moved quickly to strike a new tone for Australian diplomacy. They declared ASEAN centrality as the lodestar of their regional approach and moved to assuage anxieties in the Pacific over China’s strategic reach and climate change. And while the fledgling government has broken with the Morrison government’s tendency to shout at China, it also does not wish to be wedged by its political opponents on national security matters so early in its term.

The room for maneuver was always going to be very tight. It just got a whole lot tighter with the fallout from the Pelosi visit. It means that Canberra and Beijing are once more talking past each other. The crisis over Taiwan has only sharpened the rhetorical swords. When Foreign Minister Penny Wong joined with her American and Japanese counterparts to condemn China’s display of brute force over the Taiwan straits – in what amounted to a virtual blockade of the island – the Chinese embassy in Canberra resorted to its wolf warrior diplomacy, demanding that Australia treat its handling of the “Taiwan question with caution,” and reminding Canberra of Japanese aggression towards Australia in the Second World War. Before this Taiwan crisis erupted, Prime Minister Albanese said there is still a “long way to go” with China and that the relationship will remain “problematic.” In the wake of the Pelosi visit to Taiwan and its emboldening effect on belligerents in both Beijing and Washington, those words now seem quaint. Australia is now intimately linked to possible war in the Taiwan Strait by bipartisan policy.

It should also be remembered that the government did leave key national security officials in place – the very same officials who crafted the response to China from 2017. A new narrative is now trying to take hold, that the Morrison government’s policy, and Labor’s continuity of it, means Canberra has the diplomatic “upper hand” in its relations with Beijing. I am not sure this kind of triumphalism on the part of self-serving former officials is either wise or accurate. But that is certainly where official thinking is. It will now be for Labor, though, to reckon with the electorate about how it will afford both the new AUKUS nuclear powered submarines and all the military bells and whistles of an increased defense capability. The reality is that the previous government talked the hot talk of war but made something of a mess of actual defense preparedness. It has fallen to Labor now to clean this up. But it is going to involve some painful decisions with wider ramifications for the economy and indeed other policy settings.