On Wednesday, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov landed in Naypyidaw for meetings with high-ranking members of the country’s military government.

The meeting offered perhaps the most comprehensive understanding of the bilateral relationship that has blossomed against the backdrop of the carnage in Ukraine and the intensifying nationwide conflict in Myanmar. Lavrov described Myanmar as a “friendly and longstanding partner,” and said that the two nations “have a very solid foundation for building up cooperation in a wide range of areas.”

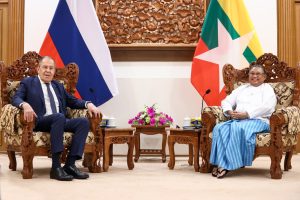

Prior to departing for Cambodia for this week’s Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) meetings, Lavrov met the military-appointed foreign minister, Wunna Maung Lwin, and junta chief Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing.

Crucially, Lavrov said that the Russian government was “in solidarity with the efforts aimed at stabilizing the situation in the country,” employing the junta’s code for its ruthless efforts to defeat the broad-based resistance to its rule. He also wished the State Administration Committee (SAC) success in the elections that it is planning to hold in August 2023 in order to launder its seizure of power into something palatable to the outside world.

“We appreciate the traditionally friendly nature of our partnership, which is not affected by any opportunistic processes,” Lavrov added.

Reporting on the meeting between Lavrov and Min Aung Hlaing, the state-run Global New Light of Myanmar described the two nations’ ambitions to become “permanent friendly countries and permanent allies” who will aid each other to “manage their internal affairs without external interference.”

These effusions came on the same day that foreign ministers from the remaining nine ASEAN member-states (the junta’s envoy was not invited) met in Cambodia and discussed the crisis in Myanmar, amid increasing calls for the bloc to abandon its Five-Point Consensus peace plan, for a lack of junta cooperation.

Relations between Myanmar and Russia have been on the upswing for some time. Moscow is a key supplier of arms to Myanmar’s military, and Russia has provided postgraduate education to at least 7,000 Myanmar officers since 2001.

But as a briefing by the International Crisis Group (ICG) released yesterday noted, the Myanmar coup and the Russia-Ukraine war have pushed the two sides into a strong mutual embrace. Russia has provided unstinting support for the junta since its seizure of power; it was one of the few nations to send representatives to the Armed Forces Day parade in March 2021, which coincided with violent crackdowns on anti-coup protesters, and has kept up its weapons shipments to Myanmar.

At the same time, the SAC has voiced strong support for Russia since its invasion of Ukraine, even as Myanmar’s ambassador to the United Nations, who has pledged his support to the democratic resistance, has voted in favor of resolutions condemning Moscow’s aggression. The day after the invasion, a junta spokesperson said the invasion was “justified for the sustainability of their country’s sovereignty.” Last month, SAC chairman and junta chief Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing visited Moscow, where he spoke with Russian officials about deeper defense cooperation and possible collaboration on energy projects.

“Facing stronger international sanctions and diplomatic isolation, the two countries are actively exploring ways to strengthen their security and economic ties,” the ICG briefing stated.

There is a sort of inevitability to this toxic convergence: increasingly isolated from the West, Myanmar’s military regime has looked to Moscow for advanced weapons systems and technical training of military officers that it may soon struggle to get elsewhere, and also a hedge against becoming too reliant on China, which has also chosen to recognize the SAC government.

For Russia, closer relations with Myanmar offer a chance to drum up arms sales, while undermining the Western attempt to rally a global coalition to counter Russian adventurism in Ukraine. Given their mutually besieged state, the ICG noted, Myanmar and Russia “are likely to ignore the possible long-term disadvantages of their growing relationship in favor of short-term benefits. ”

All this spells complications for those nations seeking to punish the two governments for their respective transgressions. The ICG briefing said that while there is little these nations can do to head off this pariah-state solidarity, concerned countries “should continue imposing targeted sanctions on Myanmar’s military regime, enforcing bilateral arms embargoes, and pressing [ASEAN] members to continue excluding the regime from high-level meetings to dent its legitimacy.”