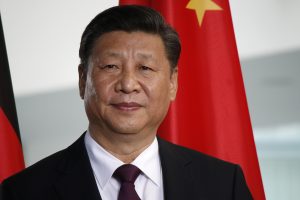

On Monday, Xi Jinping and other senior Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders attended a 30,000 square meter exhibition titled “Forging Ahead in the New Era.” For the past five years, the term “new era” (新时代) has appeared with increasing frequency in China’s white papers, propaganda, official speeches, and public diplomacy. Further declarations pertaining to the “new era” are certain to feature in the CCP’s public messaging during the 20th Party Congress, to be held in mid-October, heralding both achievements of the “new era” so far and promises of what is to come.

Why is this important? The discourse of a “new era” is hardly unique to Xi Jinping’s China. Various parties and regimes around the globe use the hyperbole of historical eras to associate themselves with progress and their critics with antiquity. See, for example, U.K. Prime Minister Liz Truss’ comments at the United Nations last week, where she proclaimed a “new Britain for a new era.” A year earlier U.S. President Joe Biden declared a “new era” of U.S. diplomacy. Hu Jintao also made a single reference to a “new era” during his speech at the 17th Party Congress in 2007.

The difference between these examples and today’s China is the growing centralization of power around Xi Jinping. The “new era” – connoting a fundamental historical shift – has been systematically fused with the persona of Xi in Chinese official discourse. This process began in earnest with the 19th Party Congress in 2017 and Xi’s keynote speech, in which a “new era” was mentioned 46 times. Since then, the “new era” has been retroactively applied in official statements to refer to the period following the 18th Party Congress in 2012, equating the “new era” to all of Xi Jinping’s tenure as general secretary of the CCP.

The Xi Jinping Era

From early on in his premiership, it was clear that Xi Jinping sought historical significance greater than that of his two immediate predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin. This was also encouraged by a growing Chinese nationalism, which predates Xi. In a 2014 journal article, retired PLA officers Liu Mingfu and Wang Zhongyuan wrote: “The era of Xi Jinping has two meanings: the era of Xi Jinping in a narrow sense is the next 10 years, which is limited by Xi Jinping’s term of office. In a broad sense, the era of Xi Jinping refers to the next 30 years… and the successful realization of the Chinese Dream.”

Liu and Wang were prescient in understanding how the language of an “era” could be used to extend Xi Jinping’s political power, even beyond the deadline demanded by succession norms. In 2018, presidential term limits were formally removed from China’s constitution. In 2017, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” was added to the CCP constitution. These constitutional changes instruct the party and the state to think in terms of pre- and post-Xi.

The CCP is well known for mobilizing history in support of the regime. Party historical resolutions to this end have been issued under Mao Zedong (1945), Deng Xiaoping (1981), and Xi Jinping (2021). However, the 2021 historical resolution refers to “periods” (时期) for the achievements made under Mao and Deng’s rule, and “era” (时代) for those under Xi. Similarly, during a speech to the Communist Youth League in May 2022, Xi made the period/era distinction between the two previous leaders and himself. An “era” is more momentous than a “period” in Chinese – creating an intentionally grander historical context for Xi.

So what is the “new era”? Despite a growing body of Chinese literature on the “new era,” these analyses tend to simply stress the importance of following “Xi Jinping Thought.” The most comprehensive outline of the “new era” can be found at the source, Xi’s (three hour) speech at the 19th Party Congress:

Chinese socialism’s entrance into a new era is, in the history of the development of the People’s Republic of China and the history of the development of the Chinese nation, of tremendous importance. In the history of the development of international socialism and the history of the development of human society, it is of tremendous importance.

For Xi, while the “new era” is scalable from the local to the international context, it is ultimately all about China: “It will be an era that sees China moving closer to center stage and making greater contributions to mankind.”

As such, the “new era” has been interpreted by many international observers as China entering a new phase in its history due to changes in its material power. From this perspective, the new era can be seen in charts depicting changes in China’s GDP per capita, military spending and technological advancement. However, I argue that the “new era” is better understood as a form of “discourse power” (话语权) that seeks to legitimize the centralization of power around the CCP and, specifically, Xi Jinping.

The Discourse Power of a “New Era”

The notion of a “new era” is embedded in a Marxist-Leninist understanding of historical development through the lens of dialectic materialism, or historical materialism. The discourse of a “new era” places China under Xi Jinping within a specific stage of socialist development. The “new era” is also derived from a narrative of national rejuvenation that long precedes Xi, based on ideas of China’s historical place in the world, a lingering victim mentality, and the project of developing China’s comprehensive national power.

As a result, the prevalence of rejuvenation discourse under Xi is not surprising – this has permeated Chinese political discourse since the foundation of the PRC. But equally Xi did not need to declare a “new era” to align his leadership with a pre-existing narrative of national rejuvenation. From 2012 it was already clear that his time as China’s leader would likely coincide with the first centenary goal of achieving a moderately prosperous society. But Xi actively went one step further, and transposed another temporal framework over Chinese history with the concept of a “new era.”

Rather than a specific political agenda, the language of a “new era” is a powerful example of how Xi understands discourse power as a tool to advance broad normative change and to strengthen his personal power. Adding “in the new era” or “for the new era” to statements on various policy areas, such as security, development, diplomacy, poverty alleviation, human rights, evokes the context of an inevitable and objective tide of change. Moreover, it ties Xi Jinping to that change. This seeks to create the space for more radical departures from previous domestic and international norms.

The “New Era” as a Source of Legitimacy

The discourse of a “new era” serves three functions. First, it bolsters the CCP’s legitimacy in a domestic context. “New era” is plastered across China’s state media landscape, where each day multiple articles, editorials, and news segments are devoted to a particular item “in the new era.” This acts as propaganda for the idea that the CCP is now operating under different conditions. This framing allows Xi to diverge from long-standing political and economic decision-making norms such as a Dengist approach to market regulation, or the two-term limit for China’s president, by making Xi’s measures seem timely in a changing world. As Xi said in 2017, “as history progresses and the world undergoes profound changes, the Party remains always ahead of the times.”

The “new era” is also used to provide the context for sensitive issues such as Tibet, Xinjiang, and Taiwan – Xinhua reported in 2020 that Xi said “facts prove that the party’s policies on Xinjiang in the new era are completely correct and must be adhered to in the long term.” And in August the State Council released a white paper titled “The Taiwan Question and China’s Reunification in the New Era.”

Second, the discourse of a “new era” is used to empower the CCP and challenge norms internationally. The strongest example was on February 4, when Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin released a joint statement on “International Relations Entering a New Era,” a major foreign policy declaration that aligned China with Russia weeks before the invasion of Ukraine. In the past couple of years, China has also begun referring to “comprehensive strategic partnership for a new era” (emphasis added) with certain parties, including Russia and Uzbekistan, in what seems like a soft extension of its tiered partnership diplomacy.

The discourse of a “new era” is also used to challenge the U.S., NATO, and Western countries that belong to the “old,” unipolar era of global politics. The “new era” is presented by China as the just temporality of a multipolar, post-imperial world. This can be seen in the way the “new era” is increasingly used in Chinese public messaging to provide context for South-South relations, such as the eighth Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in November 2021. This messaging paints Xi Jinping as the figurehead of a “new era of international relations” in an attempt to bolster his legitimacy as a global leader in a changing world (not necessarily successfully).

Third, the discourse of a “new era” serves to reinforce the idea that the government of China, and the governance of Xi, is always thinking in the long term, operating on fundamentally different time scales to the Western world. This reinforces certain orientalist tropes that China is inherently “better” at grand strategy. Despite its popularity, this narrative disguises the reality that Xi and the CCP are often as short-sighted as other regimes – the chaotic “zero-COVID” policy is just one example. This reminds us that we should take the narrative of a “new era” with a fair degree of skepticism.

The New Era after the 20th Party Congress

As we approach the 20th Party Congress, many expect to see the formal contraction of the lengthy “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in the New Era” to simply “Xi Jinping Thought” (习近平思想). As David Bandursky of the China Media Project noted, this would be an important consolidation of Xi’s long-term power. Bandursky wrote: “These abbreviations, far from being incidental, must be regarded as chess moves in the longer rhetorical game, in which the ultimate victory will be the final transformation of Xi Jinping’s 16-character banner term into a 5-character banner term.”

However, I think we are more likely to see increased usage of “new era” in official discourse. The real “victory” for Xi Jinping is perhaps the 8-character “Xi Jinping Thought in the New Era” (习近平新时代思想). This temporal element ties Xi to both his Marxist roots and the future of China’s rejuvenation, and distinguishes his doctrine from both Mao and Deng’s. The discourse of a “new era” works to place Xi as the center of gravity in China’s space-time.

In sum, we should recognize the “new era” as an emergent strategic narrative that is seeking to further political objectives. Academics, policymakers, business circles, and analysts should go further to understand the implications of China’s exercise of “discourse power.” We should not take the so-called “new era” for granted.