Uzbekistan has a rich and diverse history. The number of museums has increased significantly in recent decades – from only 88 museums across the country in 2000 to 127 in 2021. They preserve over 2.5 million items, including 112,000 artifacts and art objects that are considered to be unique in the world. In a meeting held earlier this year, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev complained that over 3,000 rare artifacts treasured as cultural heritage of the nation were lost from 14 museums. The overall damage caused by looting since independence is estimated to exceed 4 trillion Uzbek soms ($355 million).

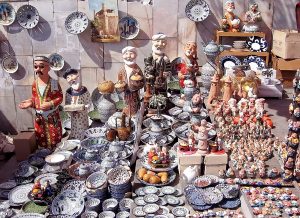

Stealing artifacts from museums is not something new in the country. While there was a single publicized case of robbery at the Ichan-Qal’a state museum in Khiva in 1992, in most other cases, museum items were replaced with counterfeits and the originals sold, especially during the 1990s amid the period of economic stagnation following independence. Most items were allegedly sold to tourists for a penny or two.

“One of the most corrupt spheres in Uzbekistan is cultural heritage,” says Kodir Kuliev, a local anti-corruption expert in an interview with The Diplomat. “Due to extravagant spending and large corrupt proceeds involved in this field, the economic loss of this system, whose magnitude is huge, is always kept below the radar. Corruption loves blurry laws and regulations and ample discretion.”

In 2020, investigations found that a director of the State Art Museum of Uzbekistan, Mirfayzi Usmonov, together with his colleagues (13 people in total) swapped 178 original paintings with replicas to sell on the black market. Of them, seven paintings were sold to a Russian citizen for $5,100.

It is rarely known precisely when and who committed such crimes. For instance, at the Bukhara State Museum, recently 81 articles of cultural heritage worth 31.5 billion Uzbek soms were found to be replicas, while an investigation into the falsification of more than a hundred items in Ichan-Qala museum in Khiva began earlier this year.

In a similar scheme, in June 2022, 70 items, including 56 paintings, were found to be fakes and two more items were missing from the Fergana Regional State Museum of History and Culture. According to Jahongir Toybolayev, a museum staff member, the investigations established that some coins in the museum’s collection were indeed fake. However, the same cannot be said about the paintings according to him – there is a possibility that some of the paintings could have been forgeries when the museum initially received them.

“[C]orruption in the sphere of cultural heritage in Uzbekistan has always been of great possibility with the involvement of high-level officials with excessive monopoly power over cultural heritage, unregulated or un-checkable discretion to decide e.g. who steals tangible heritage assets or replaces them with fake ones and conceal the whole process or who gets the service or goods in the sphere of cultural heritage. Of course, this results in limited accountability,” explains Kuliev.

Fergana State Museum’s looting saga does not stop with forged artifacts. Not only were original artifacts lost, but responsible officials stole nearly half of the 3.1 billion Uzbek soms allocated for the museum’s renovation. “City Building” LTD, the company that won the tender to renovate the museum in 2020, reportedly still has not finished the job either.

While Museum staff members forge and loot artifacts, law enforcement agencies also try to get their hands on the “business.” Fergana State Museum handed over 21 art objects to the Department of Internal Affairs of the Fergana region in 2011. Only 14 of them were returned to the museum between 2016 and 2020, while seven other paintings that were turned over have still not been found.

To amend the chaos around local museums, by the end of the year, all museum exhibits are to be re-registered and compiled in an electronic database and the process has already begun. Mirziyoyev also stated that responsibility for the museums now lies with regional governors.

But are those measures enough? “One big step, in the battle against corruption, is to train journalists in understanding the nature and the workings of corruption … once the story is out there, follow-up actions are essential,” concludes expert Kuliev. “Also, education is important. If the people and the authorities do not have a full understanding of our culture and cultural heritage and their great contribution to development, any method used to fight corruption in this area is null and void.”