Effective regulation must strike a delicate balance between encouraging innovation while at the same time discouraging excessive risk-taking. If regulation is too strict, it may stifle progress; if regulation is too lenient, it may fail to prevent fraud that can threaten the stability of the economic and financial system. In resolving this trade-off, China relies heavily on flexible implicit regulations that complement explicit rules. This reliance on implicit regulations sometimes creates ambiguity, which the Chinese business culture is quite comfortable with. This ambiguity is not equivalent to breaking the law, however. On the contrary, it helps the firms and the government navigate a fast-paced environment in which the issuance of formal rules cannot possibly catch up with the rapidly changing landscape.

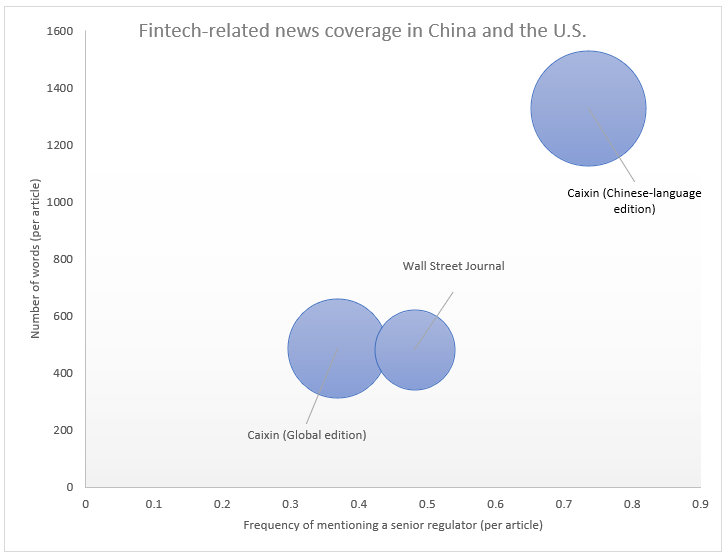

Implicit regulations are norms that have not been codified into formal rules but that nonetheless provide guidance for acceptable behavior. In China, such implicit regulations are often expressed as opinions of senior government officials. These opinions are featured much more heavily in Chinese news outlets compared to their Western counterparts. For example, a comparison of fintech-related news between leading Chinese and U.S. news outlets shows that Chinese-language media are far more likely to mention a senior government official than news pieces written for a Western audience. Strikingly, these differences in terms of coverage exist even between media outlets owned by the same publisher but targeting different audiences (such as Caixin’s Chinese-language and English-language editions). These differences in business news coverage reflect the importance of implicit regulations in China.

This figure compares the coverage of fintech-related business news in English-language and Chinese-language media outlets. The vertical axis shows the average number of words per article, while the horizontal axis shows the average number of times that a senior regulator is mentioned in an article. The size of the circles indicates the number of articles that mention the term “fintech.”

Implicit regulations have the advantage of being flexible, which enables the government to respond quickly to rapidly changing circumstances. Flexibility, however, may lead to arbitrariness, which, in turn, can sabotage the very purpose of regulation as a set of rules that everyone must follow. There are at least two factors that keep the arbitrariness of China’s implicit regulations in check. First, the strength of the Chinese government combined with its overarching focus on economic prosperity keeps the incentives of individual regulatory entities in check. Second, China’s long legal history has carved out a role for implicit regulations while at the same time maintaining the supremacy of written rules.

Because Chinese regulators by and large strive to promote economic growth, the interplay between China’s implicit and explicit regulations follows a predictable pattern. Initially, innovation (including financial innovation) is often allowed to develop with few if any explicit rules. If and when signs of misbehavior appear, regulators step in by providing implicit guidance rather than issuing explicit rules. If implicit guidance is insufficient to rein in the excesses that government officials are concerned about, explicit (and often strict) regulations follow.

When explicit regulations are enacted, they create a flurry of new rules. While these rules may seem arbitrary to an outside observer, they simply codify the implicit (and therefore publicly unobserved) guidance that preceded them.

A recent example of this regulatory cycle is the evolution of Chinese peer-to-peer (P2P) lending. P2P outlets appeared in China in 2007, but it was not until 2014 that the very first explicit regulation targeting this industry was issued. Initially, senior Chinese officials expressed positive views about the industry. On November 9, 2015, for example, China’s President Xi Jinping delivered a speech calling for the development of inclusive finance. As P2P’s growth accelerated, signs of fraud appeared and defaults proliferated. The government, however, did not outlaw P2P outright. Instead, it started sending strong signals that financial misbehavior and fraud should cease. In a marked shift in the government’s position, Xi called out some specific P2P lenders by name (E-zubao and Zhongjin) stating that they engaged in fraudulent activities that must stop. Eventually, the government issued a range of explicit rules in 2019, which effectively shut down the P2P industry in China.

The history of P2P lending holds lessons about the logic of Chinese regulation more generally. First, because of a substantial implicit component, China’s regulations may shift quite rapidly. Second, formal explicit rules typically follow government officials’ implicit guidance, but such explicit rules are hard to reverse once instituted. Third, China’s ability to use implicit regulations relies on state power, which, if necessary, can transform or shut down entire industries (as was indeed the case with P2P lending). This logic is applicable not only to P2P lending but also to other fast-paced sectors such as e-commerce, AI, and bio-medical industries.

How can Western business leaders adapt to China’s unique regulatory environment? First, they need to become comfortable with ambiguity, which in China creates space for innovation and allows firms to experiment. Second, business leaders must pay close attention to the spirit of the law and not just to its letter. One source of information about the law’s spirit are official pronouncements by government leaders. Third, in no circumstance should firms disobey the written rules: Ambiguity in China is not an invitation to break the law.