Last month was the 20th anniversary of the first ever Japan-North Korea summit meeting. Prior to that historic meeting, North Korea had long claimed that the Japanese abduction issue was a “fabrication by the Japanese government,” but following tenacious negotiations by the Koizumi Junichiro administration, the then North Korean leader Kim Jong-il acknowledged the abductions and apologized for them. Through an agreement between the two countries, five abduction victims who had been imprisoned in North Korea for a quarter of a century were returned to Japan on October 15. The sight of the five disembarking from the government plane literally brought people to tears all across Japan. The fact that North Korean agents had invaded Japan territory to kidnap Japanese citizens was kept a secret until 2002, so everyone was heartbroken to find out that the abduction victims had been living under hellish conditions without being able to let their families know they were even alive, let alone their whereabouts.

Meanwhile, there were other victims North Korea has denied abducting or has reported “dead.” Japanese felt deep resentment at their fate. Arguably the best-known of the victims is Yokota Megumi, who was just 13 when she was abducted.

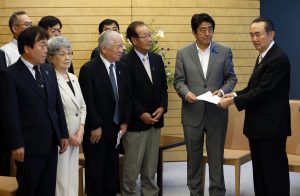

The popularity of then Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary Abe Shinzo, who took a particularly hardline stance on the abduction issue, skyrocketed. In 2006, Abe became the youngest prime minister in Japanese history. The Abe administration set up a “Headquarters on the Abduction Issue,” allocating it a substantial budget. Abe boasted countless times that he would be “ensuring the safety and the immediate return to Japan of all the abductees,” but negotiations with North Korea proved difficult, beset by mutual distrust. Although Abe would go on to hold office for 2,822 days, the longest in Japan’s constitutional history, not a single additional victim was recovered. Although there were no concrete results, the majority of the public continued to support Abe’s hard line on the issue. In the meantime, the image of North Korea in Japan has deteriorated sharply.

Following Abe’s assassination in July this year, however, a number of hitherto unknown facts about the abduction issue have come to light. Government officials have begun to offer new testimonies, offering more insights into why the Japan-North Korea negotiations were derailed.

First, we have the important testimony of former Foreign Vice-Minister Saiki Akitaka. In 2014, North Korea promised to conduct a survey of all Japanese still in North Korea from the end of the Second World War, to include the abduction victims. In return, Japan would lift its own sanctions. This was the so-called Stockholm Agreement.

The Japanese government has always claimed that the North Koreans never produced a proper report, but it turns out that the circumstances were actually more complicated. It has now been revealed that North Korea did report that two abduction victims, Tanaka Minoru and Kaneda Tatsumitsu, were still alive, but the Abe administration refused to accept the report.

Tanaka and Kaneda, unlike Yokota Megumi, were men with no known relatives in Japan. Even if they were to return home to Japan, there would be no joyous images of them being greeted by weeping family members. The Abe administration may have decided that reclaiming these two men would do little to satisfy the Japanese public, and in fact could even create more pressure to get answers on Yokota and the other victims. As a result, the Japanese government treated the two men as if they had never existed. For a government that had continuously referred to the abductions as the “most important issue,” this seems a breathtakingly callous decision. Following this decision, North Korea became harshly critical of Abe, with the result that negotiations were suspended.

Also notable is the testimony, former Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo. In an interview with Kyodo News, Fukuda reflected on the circumstances surrounding the return of the five abduction victims in October 2002. At the time, it was said that Japan and North Korea had agreed not to return the five permanently, but rather to have a two-week “temporary return.” However, it has been claimed on numerous occasions that opinions within the Japanese government were split between keeping the five in Japan, and thus breaking the “temporary return” pledge with North Korea, or sending them back to North Korea for the time being. Then deputy chief cabinet secretary, Abe was believed to have been staunchly opposed to any return. The conventional wisdom is that it was this hardline stance that helped raise Abe’s standing among the Japanese public to unprecedented levels.

But according to Fukuda, the reality was quite different. First, it was only at the end of August that he even became aware that Abe was involved in behind-the-scenes negotiations to arrange the summit with North Korea. Moreover, there is no way that Abe would have been in a position at the time to overrule then Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro or Fukuda, who at the time was chief cabinet secretary.

Public opinion in Japan has paid scant attention to these important testimonies, with the result that inaccurate perceptions of Abe’s North Korea policy still persist in Japan.