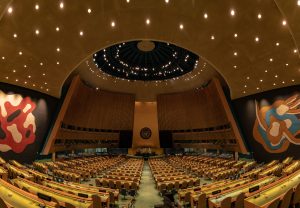

Yesterday, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voted on a resolution condemning Russia’s “illegal so-called referendums” in Ukraine and demanding that it reverse its “attempted illegal annexation” of four Ukrainian provinces.

The resolution passed handily with the support of 143 nations, while 35 abstained. Just five – aside from Russia, the unsavory coterie consisting of North Korea, Syria, Belarus, and Nicaragua – voted against the motion.

One puzzling element of the resolution’s passage was the behavior of Thailand, one of three Southeast Asian nations to abstain from the vote. The others were Vietnam and Laos, one-party communist states whose longstanding relations with Russia (and before it, the Soviet Union) have prompted them to abstain or vote against the major U.N. resolutions pertaining to the Ukraine war.

In a statement published today, Suriya Chindawongse, Thailand’s permanent representative to the U.N., reaffirmed that Thailand “holds sacred the U.N. Charter and international law” and was opposed to the “unprovoked acquisition of the territory of another State by force.” At the same time, Thailand chose to abstain because the vote is taking place in “an extremely volatile and emotionally charged atmosphere” that minimalizes the “chance for crisis diplomacy to bring about a peaceful and practical negotiated resolution to the conflict.”

But the Thai vote remains confounding for a number of reasons. Unlike, say, India, which has abstained consistently on the various UNGA votes related to the Ukraine war, Bangkok voted in support of UNGA Resolution ES-11/1 on March 2, which condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and demanded a full withdrawal of its forces from the country. On the surface, Thailand also has little to lose in its relations with Russia, which is neither a significant economic partner, nor (unlike Vietnam) a crucial source of arms.

A decent number of Russian tourists have historically visited Thailand – around 1.4 million did so in 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic – but this is clearly not enough to shift votes in the UNGA. Indeed, Russian tourist arrivals to Thailand could conceivably grow as young men and their families flee conscription into the Russian army.

While an abstention may make at least theoretical sense in terms of Bangkok’s desire to maintain its neutrality and give diplomacy a chance to do its work, it is hard not to decry a more self-interested motive.

On the same day that the UNGA vote took place, it was reported that Russian President Vladimir Putin had belatedly accepted Thailand’s invitation to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Bangkok next month. The question of Putin’s presence at the November 18-19 summit had been unclear for some time, and until this confirmation, China’s leader Xi Jinping was the only one among the leaders of the great powers to have confirmed his attendance at the APEC Summit.

As The Diplomat’s columnist Tita Sanglee wrote in these pages recently, Thai leaders feared that Putin’s absence, and that of U.S. President Joe Biden, who will be skipping the summit in order to attend his granddaughter’s wedding, would compromise the success of the summit. Compounding the potential loss of face, both Biden and Putin are slated to attend the G-20 Summit in Indonesia, which will take place on November 15-16.

Despite the fact that Putin is for many an international pariah, his presence is still important for Thailand as this year’s APEC host. As Sanglee wrote, for Thailand, “having all top leaders from competing power blocs attending the summit and risking extra drama in the process is arguably better than having ‘incomplete’ attendance and being forgotten.”

It is not hard to join the dots and surmise that the Thai Foreign Ministry thought it prudent to abstain on the vote in order to avoid unnecessary friction with Russia. Of course, any connection between Thailand’s UNGA vote and the upcoming APEC Summit is hard to prove – but it helps explain what would otherwise loom as a confounding coincidence.