A report recently released by the University of New South Wales’ Center for Crime, Law and Justice argues that the New South Wales (NSW) government’s “law and order” response to the COVID-19 pandemic led to significant fines debt – often in low socio-economic and Indigenous communities – and damaged community-police relations.

The report comes in the wake of the NSW government withdrawing over 33,000 COVID-19 fines after a Supreme Court hearing. The case was originally brought by the Sydney-based Redfern Legal Centre on behalf of Brendan Beame, Teal Els, and Rohan Pank, and was the spark for the mass invalidation and refunding of fines.

A total of 62,128 COVID-related fines and infringements were issued in NSW during the pandemic.

Katherine Richardson, acting for the plaintiffs, said Els was unaware of what she was fined for when she was approached by police while sitting in a park after exercising with her sister.

Richardson stated that more than 160 people had received A$3,000 fines identical to Els’, and more than 500 had similar wording.

“Our submission states they are entitled to a refund. They have been charged money invalidly and we are pressing for a full range of relief to be sought,” Richardson told the court.

Redfern Legal Centre argued that their clients received little information and the fines lacked details about the supposed health order they were said to have breached.

In a statement, Redfern Legal Centre noted that “Revenue NSW withdrew one of the fines [Rohan Pank] soon after we filed the case.”

“On 29th November 2022 the remaining two cases were due to be heard. The day before the hearing, the government conceded or agreed that the two plaintiff’s fines were invalid.”

The case focused on the technical argument that the fine notices did not provide a sufficiently detailed description of the offense that was supposedly committed. This would render them void.

In a statement, Revenue NSW stated that “where fines are withdrawn, all sanctions, including drivers license restrictions or garnishee order activity will be stopped.”

“Where a fine has been withdrawn and a customer has made a payment — either in part or in full — Revenue NSW will make contact to arrange a refund or credit the payment towards other outstanding debts.”

The report by the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Center for Crime, Law and Justice noted that lockdowns in NSW – in response to the Delta wave of COVID-19 that impacted the world in 2021 – and the resulting fine burden “fell heavily on socio-economically disadvantaged individuals, families and communities.”

The report emphasized that NSW residents were caught up in a quagmire of law-and-order decision making, often dealing with “frenetic and voluminous law-making, excessive financial penalties, hyperbolic rhetoric from political leaders and aggressive enforcement by police”

Over a six-month period, 123 amendments were made to public health orders. In July 2021, 13 amendments were made over 15 days. One lasted less than four hours before being amended.

From July to September 2021, fines exceeding A$45.9 million were imposed on NSW residents.

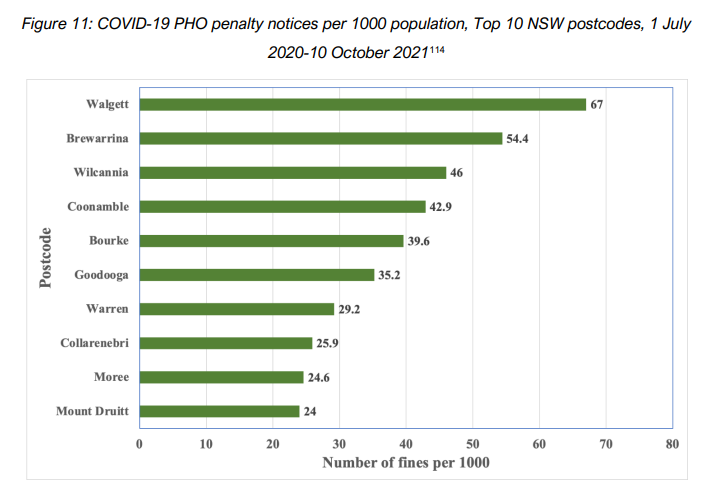

Graph Credit: UNSW CCLJ report, “COVID-19 Criminalisation in NSW: A ‘Law and Order’ Response to a Public Health Crisis?

Apart from Mount Druitt — which makes up part of Greater Sydney — the most heavily fined locations in NSW were in regional areas. They are all low-income areas, and they all contain significant Indigenous populations.

Keisha Hopgood, the principal solicitor at Aboriginal Legal Services NSW/ACT (ALS NSW/ACT), argued that “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities paid a higher cost as a result of the Government’s punitive response to COVID-19.”

“Less advantaged residents of NSW were policed and punished, rather than protected from the public health crisis.”

Alexis Goodstone from Redfern Legal Centre agreed, drawing attention to the UNSW report.

“[It] highlights the punitive nature of fines and the disproportionate impact fines have on First Nations people, children and those of low socio-economic status.”

Revenue NSW noted that the decision to withdraw some fines “did not mean the offences were not committed.” The remaining 29,017 fines would still need to be paid in full if they hadn’t already been resolved, the government office added.

In a joint media release, Redfern Legal Centre, ALS NSW/ACT, and the Public Interest Advocacy Centre called for all existing COVID fines to be cancelled, and to review the government’s “reliance on fines as a means of influencing community behavior, given the disproportionate impact they have on less advantaged and marginalized communities.”

The Law Society of NSW agreed, welcoming the “common sense” decision but insisting that the remaining fines also be dissolved.

“This decision leaves unresolved the status of more than 29,000 fines that may impose a disproportionate burden of penalties on vulnerable and disadvantaged people.”

“Many of the top fifteen per-capita locations where fines were issued during the Delta outbreak have high Aboriginal populations… Eleven of these communities are counted among communities suffering the state’s highest level of social disadvantage.”

The report, as well as the disproportionate levels of fines for Aboriginal and low-income communities, has helped to highlight what many of these groups have argued for years: an inherent targeting by police on some of Australia’s poorest residents.

CEO of the Public Interest Advocacy Centre, Jonathon Hunyor, contended that “the NSW response to COVID was symptomatic of a deep-seated problem: we reach for punitive responses to social challenges instead of looking to community engagement.”

“The report also highlights that already-disadvantaged groups bore the brunt of the fines frenzy, consistent with pre-existing bias in how police powers are exercised.”

Outside of the court after the decision, acting principal solicitor for Redfern Legal Centre Samantha Lee argued that the decision had the potential to quash all the COVID-19 fines that were issued during the 2020 and 2021 lockdowns.

“This case has set a precedent.”

In the eyes of many observers, the fines issued during lockdown simply continued a concerning pattern that has helped to entrench many – including many Aboriginal people – in poverty. The punitive measures enacted by police seem to disproportionately target the communities that are most disadvantaged by any financial penalty. The cancellation of the remaining fines would be a positive step that many advocacy and legal groups would welcome.

However, a much larger discussion around punishing people for minor infringements – often without their causing any nuisance – is needed to make sure the next health crisis doesn’t result in the same issues prevailing once again. As the UNSW report makes clear, you cannot police your way out of a public health crisis.