Kazakh authorities have impounded the property of the main operator of Baikonur spaceport due to an ongoing debt dispute. Given the tense geopolitical situation in Eurasia, there has been heightened attention to any potential rifts between Russia and Kazakhstan.

On March 7, Kazakh media reported that the Bailiff Service of the Republic of Kazakhstan had impounded the property of TsENKI (Center for the Operation of Ground-Based Space Infrastructure), a subsidiary of Russian state-owned Roscosmos, and issued a travel ban on the company’s head in Kazakhstan.

TsENKI reportedly owes a debt of 13.5 billion tenge (2 billion rubles or about $29 million) to the Joint Kazakh-Russian Enterprise Baiterek JSC. The Arbitration Court at the Astana International Financial Center (AIFC) had ruled in Baiterek’s favor last year and decided on enforcement actions back in November 2022. TsENKI was informed in late January but apparently did not pay its debt, thus the impounding and block on transferring assets and property out of Kazakhstan.

Kazakh Minister of Digital Development, Innovation, and Aerospace Industry Bagdat Musin said that negotiations are ongoing and clarified that the issue relates specifically to TsENKI, not the entirety of the Baikonur cosmodrome.

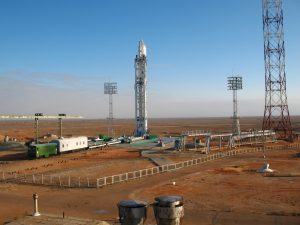

The Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan is one of the world’s most important spaceports. The spaceport was established in 1955; since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has leased the facility from Kazakhstan. In 2005, Russia and Kazakhstan agreed on an extension of the lease to 2050 for $115 million annually, plus $50 million each year for maintenance.

In 2011, when the United States mothballed its space shuttle program, the Russian Soyuz rocket and Baikonur became the only ways to send manned missions to the International Space Station (ISS).

Russia has sought to establish a facility that could replace Baikonur, give the complexities and risks of relying on a facility physically located in a different country, but its Vostochny Cosmodrome, being constructed in the Far East, has struggled. In 2016 Russian President Vladimir Putin attended the first rocket launch at Vostochny. While test launches continue, it remains under construction and beset by financial scandals.

According to local reporting, the dispute between Baiterek JSC and TsENKI “is linked with non-fulfillment of the terms of the contract for the development of a draft design of the Baiterek complex, which the Russian company received from the joint venture.” An environmental impact assessment of the Soyuz-5 rocket was supposed to take place, but TsENKI allegedly did not complete it. Baiterek JSC sought to recover the costs of the assessment, which was not actually completed.

Baiterek (also the name of an iconic monument in Astana) was formed in 2005 and envisioned a transition to rockets deemed more environmentally friendly than the Proton rockets in use at Baikonur. A new launch pad was to be built for the new rockets, but last summer Kazakh authorities announced a delay of up to year.

In August 2022 Musin met with Roscosmos General Director Yuri Borisov after which it was announced the “Baiterek project,” the first test launch for the Soyuz-5, would be pushed back to 2024. Kazakh media report that Borisov had harsh words with Musin over the delay. Musin allegedly called the criticism a “diplomatic miscalculation.” KZ24 editorialized about the incident, suggesting that Musin was “trying to drive a wedge between [Kazakh President] Tokayev and Putin.”

An adjacent, though murky, issue is the impact and influence of sanctions –both stemming from the war in Ukraine and earlier sanctions — against Russia on these kinds of joint projects. Last year, then-general director of Roscosmos Dmitry Rogozin threatened to scrap cooperation regarding the ISS. Rogozin’s hyperbole aside — ISS cooperation has not been suspended — wider ranging sanctions have certainly put pressure on the Russian space industry, and by proxy Baikonur and Kazakhstan. This may be most evident in concerns noted in Kazakh media about Astana’s ability to continue using Russian rockets for its own commercial launches.