Western security experts tend to speculate about a “Chinese way of war.” This supposedly distinct Chinese military methodology is usually presented as both unique, and centered on deception; proponents of this idea typically point to the renowned theorist Sun Tzu, or political leader Mao Zedong as inscrutable master strategists whose ways are unknown to the West. In terms of military theory, however, these two strategists – as enduring as their legacies are – do not align on key points, let alone represent an unknowable Chinese way of war.

Sun Tzu and Mao’s teachings do not embody the theoretical underpinnings of a unique Chinese way of war, but rather demonstrate widely held general principles – as evidenced by the Western application of many of Sun Tzu’s precepts, and the European influence present in Mao’s writing.

Sun Tzu’s ‘Art of War’ Is Not Unique to China

Sun Tzu’s roughly 2,500 year old text, “The Art of War,” while insightful, does not offer ideas that are representative of a Chinese way of war. Rather than providing observations applicable only to a Chinese military leader, Sun Tzu described military concepts that can be observed throughout history and have been applied outside his culture, even in the West.

One of Sun Tzu’s enduring observations that is also present in Western military tradition is the importance of deception in military affairs. Sun Tzu famously wrote that “all warfare is based on deception;” he advocates for confusing the enemy by making him “believe that you are near when you are far” and baiting the enemy in order to “lure him” into traps. Sun Tzu, however, does not hold an intellectual monopoly on deception. Militaries across the world have used military deception (commonly referred to as “MILDEC”) during major operations, as evidenced by Operation Fortitude during World War II.

Operation Fortitude exemplifies how Sun Tzu’s recognition of deception is not unique to a “Chinese way of war.” A deception operation executed by the Allies in support of the 1944 invasion of Normandy, Operation Fortitude included radio traffic generated for fictional units, inflatable tanks, landing craft made of canvas and wood, and even the creation of unit patches for nonexistent units. As a result, the Germans did not commit their Fifteenth Army Group to counter the Normandy invasion, choosing instead to retain it as a reserve for the landings they had been convinced would occur at the Pas-de-Calais. No strangers to deception, the Allies implicitly understood Sun Tzu’s maxims concerning deceiving the enemy with regards to troop dispositions and intent.

A second component of Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War” that can be observed in Western military history is the use of “secret agents” or spies. Sun Tzu wrote that “secret operations are essential in war; upon them the army relies to make its every move.” Sun Tzu described several types of spies, including those that come from the native population, and those that can be used to deliberately spread misinformation.

These insights, while valid, are not unique to China. During the American Revolution for example, George Washington employed an extensive network of spies to his advantage, just as Sun Tzu suggested a “worthy general” should.

Russell F. Weigley describes how the militarily weaker George Washington, fighting as an insurgent, depended on accurate intelligence from spies to both preserve his force and to strike at British detachments, while avoiding decisive engagements. Correspondence between Washington and one of his subordinate commanders, Brigadier General William Maxwell, reveals the extent of Washington’s emphasis on intelligence gathering; Washington stresses to Maxwell that he must “use every means in your power to obtain a knowledge of [the] enemy’s numbers, situations, and designs.”

Washington naturally understood the logic behind Sun Tzu’s maxim that an army without secret agents is “exactly like a man without eyes or ears,” and developed a system of spies who provided him with an awareness of British dispositions, enabling him to avoid battle when it would be disadvantageous.

Mao Zedong’s Western Influences

As opposed to offering a distinctly Chinese way of war, Mao’s writing reflects significant Western influence. The references to Carl von Clausewitz’ “On War” in Mao’s seminal “On Protracted War” extend significantly beyond Mao’s imitative title. Mao’s 1937 revolutionary classic is in fact suffused with Clausewitzian concepts such as the role of war as a political instrument and the idea of the primacy of policy during war.

Mao saw war as a political instrument used to achieve political aims in a very Clausewitzian sense. Quoting the great Prussian directly several times, Mao repeated the idea that war is the continuation of politics by other means, and stated that “war itself is a political action.” Mao had a larger vision beyond the war; he sought to “build a new China,” and understood that war was just a political instrument to achieve that end. Writing against those who would seek compromise with the Japanese, Mao wrote that the Japanese “obstacle” must be “swept away,” and that once the obstacle is removed “our political aim will be attained and the war concluded.” Mao accepted war’s utility as a political instrument.

He was also strongly influenced by Clausewitz’ writing on a related topic: the subordination of military aims to policy. Mao used a Clausewitzian lens to examine how military aims must be subordinated to political aims. Writing that victories must be attained “and so achieve the political aim,” Mao explained that the political aim of the war is “why the war must be fought,” with the military goals being subordinated to the political aims. Rather than represent a distinct way of war, Mao borrowed heavily from Clausewitz, who wrote that the “political object is the goal, war is the means of reaching it.” This embrace of the subordination of military aims to political aims stands in stark contrast to Sun Tzu’s preferences regarding the role of the political leader versus the military leader.

Divergent Theories

In addition to Sun Tzu’s application outside of Chinese military spheres, and Mao’s clear Western influence, the areas of discontinuity between the two theorists further demonstrate why they do not represent a unified Chinese way of war. If their writing was representative of a distinctly Chinese conception of war, their seminal texts would align on enduring strategic concepts, and not just tactical generalities present in most military doctrine, such as the importance of surprise. Sun Tzu and Mao are in fact diametrically opposed on two key concepts: protracted war and the subordination of military aims to policy.

Sun Tzu recommended against protracted war, recognizing that it drains resources, lowers morale, and leaves states vulnerable to attack from their neighbors. Mao, conversely, embraced it and literally wrote the book on protracted war. While Sun Tzu wrote that there has “never been a protracted war from which a country has benefitted,” Mao deftly orchestrated a protracted war in the face of a determined invader. This critical difference reflected their differing strategic contexts and further illustrates that Sun Tzu and Mao are not a Chinese strategic dyad representative of a Chinese way of war.

As noted, Mao clearly adopted Clausewitz’s views regarding the subordination of the military aim to political aims. Sun Tzu preferred that policy not permeate war, writing that victory results from an able general who is “not interfered with by the sovereign.” In Sun Tzu’s view, once a political aim is set, the conduct of the war is strictly within the purview of the general, who functions independently. Sun Tzu and Mao are diametrically opposed on the role of the political leader and influence of policy on the conduct of war – a key and fundamental difference.

As evidenced by their opposing views on protracted war and the subordination of military aims to political aims, Sun Tzu and Mao do not even reflect the same views on major strategic perspectives, let alone represent a unique theoretical framework for a Chinese way of war.

Knowable Unknowns

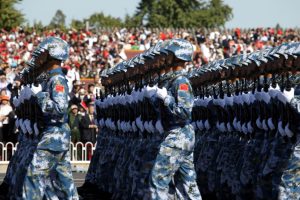

If there is no uniquely Chinese way of war, Western militaries can be more confident in forecasting potential Chinese plans or strategic approaches in multiple scenarios. Using this line of reasoning, Chinese operational planning may very well follow a process similar to Western approaches, which would allow for better anticipation of both their aims and methods. While one must always guard against mirror imaging, it is hard to ignore some People’s Liberation Army (PLA) reforms that appear to be inspired by Western organizational structure, doctrine, and experience.

Multiple Chinese reforms and initiatives look to be directly influenced by and comparable to features of the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD). The 2016 PLA formation of five Theater Commands out of what were formerly seven military regions appears to have been influenced by the U.S. Combatant Command organizational structure. The Theater Command reform was done in the name of improving “jointness,” a concept that the PLA has pursued in an iterative fashion since it observed the rapid success of the U.S.-led coalition during the 1991 Gulf War. Even at the tactical level, PLA reforms replicate U.S. wargaming scenarios that involve specially trained Opposing Force (OPFOR) role-players. These structural and doctrinal commonalities, combined with the above-stated similarities of two pillars of Chinese military theory and Western military theory and practice, bolster the conclusion that it is increasingly unlikely that the West need fear a unique and mysterious Chinese way of war.

Sun Tzu and Mao do not represent a Chinese way of war that is markedly different from the West, but they do demonstrate that the astute strategist who is aware of both history and the specific strategic context is capable of crafting theories that can be influential for decades – or even centuries. History shows that Western militaries have acted in accordance with Sun Tzu’s strategic concepts.

Recognizing that China, influenced by Sun Tzu and Mao, does not subscribe to a Chinese way of war is hugely relevant for the modern strategist. Rather than simply reducing any potential Chinese military strategy to a formula as simplistic as “deception is the Chinese way of war,” there is more utility in considering China’s modern strategic context.

Perhaps to better anticipate a modern Chinese way of war, one must consider the late Colin Gray’s description of the component parts of a nation’s strategy as the “dimensions of strategy.” Gray’s dimensions of strategy range from culture and society, to technology and geography, with an overall total of 17 different components. Historical theorists, then, would only contribute to one part of a multi-faceted approach.

In overly focusing on Chinese military theory and history as a default “Chinese way of war,” the West overlooks other dimensions of strategy – for example, the geography that make operational reach such a challenge in the Pacific, as well as the political pressures that war would place upon a regime that is always concerned with domestic control and the sanctity of the ruling party. Facing a rising China, Western strategists must look beyond popular conceptions about a mysterious Chinese way of way based on deception and espionage, and instead accept that there is utility in understanding that China is not an inscrutable competitor, but rather, potentially, a knowable one.