Since Vietnam and South Korea established formal diplomatic ties in 1992, popular culture has turned out to be the best ambassador for Seoul in Vietnam. It all began in the late 1990s when Korean television dramas (also known as K-dramas) such as “Medical Brothers” (starring Jang Dong Gun and Lee Young Ae) and “Star in My Heart” (starring Ahn Jae Wook and Choi Jin Sil) started to appear on local television thanks to some Korean corporations’ sponsorships, leading to audiences’ interest in K-pop and other Korean cultural exports like films, food, travel packages, fashion, and cosmetics.

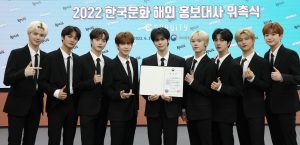

Now, after more than two decades, this Korean Wave, known as Hallyu, has remained popular in Vietnam while forging its presence worldwide. Many scholars believe this is partly a result of the Korean government’s policy to promote South Korea as a “dream economy of icons and aesthetic experience.”

According to Google Trends annual reports over the past decade, the titles of K-dramas and Korean entertainers have been consistently present in its top searches by Vietnamese people. Recent K-drama hits such as “Reply 1988,” “Descendants of the Sun,” “Crash Landing on You,” and “The Glory” became popular topics of discussion on social media. The most popular Vietnamese news websites, such as Kenh14, Zing, and VnExpress frequently report Korean showbiz events. Korean reality shows such as “Running Man” and “Dad! Where Are We Going?” have been adapted for the Vietnamese market, while local remakes of Korean films like “Em là ba noi cua anh” (I’m Your Grandma) (2015) and “Thang nam ruc ro” (The Brightest Years) (2018) became box-office hits.

Aesthetic traces of Korean pop culture in Vietnam are palpable. Images of Korean entertainers pervade public sites in Vietnam, decorating advertising billboards, department stores, and beauty salons. Phrases such as long lanh nhu phim Han (beautiful as Korean dramas), or trang nhu Han Quoc (white as Koreans —used to approvingly describe pale skin color) have entered everyday vocabulary.

The popularity of all things Korean, including food, mobile phones, and cosmetic brands, reflects a general forward-looking attitude that views South Korea as a modern and intriguing culture. While the Vietnamese show a forward-looking attitude toward the West as well, it is usually tempered with a sense of alienation due to the underlying cultural differences. South Korea as a model of Asian modernity feels closer. Its development therefore seems more attainable to the Vietnamese public. After all, South Korea’s miraculous economic growth during the latter half of the 20th century is quite recent, and Korea shares clear elements of cultural similarities with Vietnam including a Confucian cultural heritage, an emphasis on family ties and respect for the elderly, and a collectivist value that foregrounds conformity.

My interviews with Vietnamese research participants reveal that many saw in South Korea and the glamorous, metropolitan lifestyles embodied by Korean stars on screens an alluring future they wished for themselves. Some acknowledged how K-dramas’ recurring rags-to-riches stories serve as inspiration for them to reflect on their own lives and strive toward success. Portrayals of characters’ relentless pursuit of status and money in K-dramas resonate with many local viewers, who are encouraged to be self-sufficient by the Vietnamese government’s recent neoliberal social policy. Decades after the 1986 Doi Moi (Renovation) socioeconomic milestone, marked by Vietnam’s transition to a market economy and integration into global trade, the government has transferred certain welfare responsibilities to the market and now touts self-made wealth and success as patriotism.

Vietnamese enthusiasm toward Korean pop culture has not escaped criticism. Government officials and members of the public have raised charges of a cultural invasion. K-pop fandom, which has been part of the local youth culture since the mid-2000s, has triggered heated social debates and given rise to moral panic over young people’s obsession with Korean idols. This fervent reception distinguishes K-pop fandom from fan activities associated with other genres of global media from the U.S., the U.K., China, Japan, or Thailand, which enjoy some popularity in Vietnam but generally do not attract such heated debates. However, the backlash in Vietnam toward Korean pop culture has been more tempered than in some other Asian countries, never erupting into protests such as those seen in China and Japan.

A cosmetic clinic in Hanoi, named after the affluent Gangnam District in Seoul. Photo by Thi Gammon.

A Wave of Romanticism and a Women-Led Phenomenon

While the dominance of South Korean pop culture in Vietnam can be attributed to digitalization, modernization, and the rise of a consumer culture after Doi Moi, its harmony with recent socio-cultural developments in Vietnam cannot be ignored. Romantic K-dramas and sentimental K-pop ballads, which emphasize pure, idealized romantic love, self-love, and self-awareness, struck a chord with the changing local society, which has witnessed a turn to the ordinary and the private in its own media. Consuming Korean pop culture allows local audiences to indulge in various imaginations, from conjuring means to maximize the self to constructing an ideal romantic partner, entertaining desires to love and be loved, and considering new ways to express romantic emotions and express the self.

The Vietnamese absorption of this romanticism is notable for a collectivist Communist-led culture, which used to frown upon romantic self-indulgence as a product of the decadent West and the bourgeois. With the growth of the urban middle-class comes a corresponding accelerating interest in self-care products and global media consumption. Self-help books and sentimental Chinese literary novels (truyen ngon tinh) concerned with individualistic pursuits of happiness have been consumed prominently by young people and dominated the Vietnamese bookshelves.

Note also that the Korean Wave in Vietnam is very much a women-driven phenomenon. Although men consume Korean pop culture too, it is women who are outspoken about it. Romantic K-dramas appeal to many Vietnamese women’s desire for a love they never had. Those dramas tend to construct a romantic utopia through the ideal of a dream man who embodies beauty, status, and wealth, combined with undying devotion to a female love interest. Usually paired with a seemingly ordinary yet virtuous female lead, this dream man is designed to cater to women’s romantic fantasy. In Vietnam, the appeal of these romantically devoted men may be explained by women’s fatigue with misogyny (reminiscent of female Hallyu fans in Japan) and their concern with men’s unfaithfulness in a society that has historically condoned male infidelity.

The recurring role of a powerful but kind gentleman is often played by tall and handsome Korean actors, who exhibit meticulously maintained, at times effeminate, looks and soft personality traits such as tenderness, compassion, and a willingness to express vulnerability. These characteristics constitute a new gender construction known as soft masculinities, which have recently appeared in not only Korean pop culture, but also Japanese, Chinese, and Taiwanese media. Many local men mock soft masculinities in social media because of a distaste for Korean men’s performance of beauty and overtly romantic gestures, but a lot of women love them.

As some Vietnamese urban middle-class women gain more power, they come to appreciate soft masculinities and associated traits such as men’s attention to their own looks and emotional work, manifested in the effort to be understanding, supportive, emotionally expressive, and compassionate in romantic and social relationships. Korean soft masculinities have in fact exerted a visible impact on local pop culture: Vietnamese stars such as Son Tung M-TP, Soobin Hoang Son, and Isaac exemplify local versions of soft masculinities in their emulation of male Korean entertainers’ fashion and performing style.