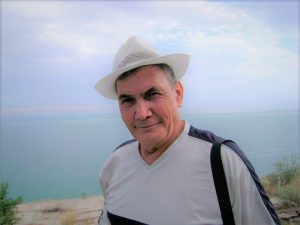

In 2019, an elderly Jehovah’s Witness was arrested in Tajikistan for “inciting religious hatred” and being in possession of religious materials published by the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Shamil Khakimov, now 72, has been in prison for more than four years. Although his sentence was reduced under an amnesty law in 2021, there are concerns that he will not be released on May 16 as planned.

“We are holding our breath, hoping Shamil will be released on May 16,” Jarrod Lopes, a spokesman for Jehovah’s Witnesses, told The Diplomat in early May. “Based on the consistently cruel way the Tajik authorities have treated Shamil, it’s not out of the realm of possibility they will refuse to release him.”

Khakimov’s case highlights the opaqueness and arbitrary nature of the Tajik justice system and the lack of religious freedom in Tajikistan.

Jehovah’s Witnesses, a Christian denomination known for their door-to-door proselytizing, were legally registered in newly-independent Tajikistan in 1994 and re-registered in 1997. But a decade later, in 2007, Tajik authorities revoked their registration on grounds that they were “distributing in public places and at the homes of citizens… propagandistic books on their religion, which has become a cause of discontent on the part of the people.” The Jehovah’s Witnesses appealed the decision but were denied, with Tajik authorities further claiming that they had violated domestic laws by individual Jehovah’s Witnesses requesting to substitute compulsory military service with “civil alternative service”; that they were “distributing fanatical and extremist religious materials”; and finally, that they were “conducting activities that could potentially lead to sectarian conflicts.”

Jehovah’s Witnesses, in general, do not participate in politics; they do not vote, run for office, or protest. They also refuse to participate in military service, qualifying in many countries as “conscientious objectors.” Many are, however, willing to perform alternative civilian service.

Tajikistan’s crackdown on Jehovah’s Witnesses came two years before Russia’s more publicized campaign against the group, which began with a case in Taganrog in which a court decided that the organization incited religious hatred by “propagating the exclusivity and supremacy” of their religion. In 2017, Russia branded the Jehovah’s Witnesses a “extremist group.”

This logic has been imported back into Tajikistan, with Lopes noting that Tajik courts, “including the one that convicted Shamil, have issued judgments against Jehovah’s Witnesses that refer to Russia’s Supreme Court decision in April 2017, which effectively banned the Witnesses’ activity.”

In recommending that Tajikistan again be designated as “country of particular concern” regarding religious freedom, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) highlighted Khakimov as a “religious prisoner of conscience.”

In 2022, USCIRF Chair Nury Turkel spoke out against Khakimov’s imprisonment: “For three years, Khakimov has been forced to rot in prison because of his peaceful religious activity. Tajik authorities have refused to provide proper medical care for the open sores on Khakimov’s leg; they refused to allow him to attend the funeral of his son — his only allowed visitor in prison; and they have refused to let him share his faith or read his Bible in public.”

USCIRF’s 2023 Annual Report states, “Tajik authorities targeted the nonviolent 71-year-old for sharing his faith in public and have denied him access to adequate medical care. In November 2022, the Khujand City Court rejected Khakimov’s request for transfer to a specialized hospital to treat signs of gangrene in his legs and poor eyesight, again disregarding UNHRC… requests for Khakimov to receive proper medical treatment.”

When he was arrested in 2019, Khakimov had just had surgery on his leg and reportedly suffered from an open wound and ulcers. His condition has not improved, and in November 2022 the court in Khujand denied another request to transfer him to a hospital.

Beyond the humanitarian argument that Khakimov deserves better medical treatment, Lopes underscored in comments to The Diplomat that “there is no legal reason, according to Tajik and international law, for a peaceful man like Shamil to be in prison.”

According to the Jehovah’s Witnesses, in 2020 Tajik President Emomali Rahmon signed into law amendments that, among other things, decriminalized advocating “religious superiority” — the article under which Khakimov was convicted — moving it from Article 189 of the Criminal Code to the Code of Administrative Offenses. This made it punishable by fine or brief 5-10 day jail term, not the 7.5 years Khakimov was originally sentenced to.

But efforts by the Jehovah’s Witnesses to have Khakimov’s case reconsidered on these grounds have met with repeated denials.

“The authorities have refused multiple requests to have Shamil’s case reviewed based on the amended law code,” Lopes said. “Instead, prison authorities have threatened Shamil that he won’t be released until he ‘repents’ and formally renounces his beliefs.”

The United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) has made several requests for Khakimov’s immediate release and access to medical treatment.

In 2022, the UNHRC reviewed a separate case submitted by Tajik Jehovah’s Witnesses and essentially dismissed Tajikistan’s three reasons for refusing them registration. The committee first noted that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR), to which Tajikistan is a party, establishes “the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion,” and the right to conscious objection can be derived from that provision. Second, regarding Dushanbe’s claim that the Jehovah’s Witnesses were distributing materials that disturbed people, the committee noted that the state provided no evidence to support that claim. And finally, Dushanbe’s claim that the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ activities could lead to conflict flew in the face of the group’s principles, which are notably pacifistic (hence the objection to military service in the first place).

On April 13, 2023, Jehovah’s Witnesses in Tajikistan were notified that a court in Dushanbe would hold a hearing the next day considering their petition on the bases of the UNHRC opinion. Vladimir Adyrkhayev, chairman of The Religious Association of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Dushanbe, successfully requested the court to delay the hearing to the following Monday, April 17. Representatives of the U.S. and U.K. embassies, as well as a representative of the U.N. Special Rapporteur for freedom of religion or belief (who happened to be in Tajikistan at the time) reportedly attempted to attend the hearing but were denied entry. After about an hour, the hearing ended and the judge dismissed the application for the reconsideration of the ban on the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Although Tajik authorities said the judgment would be made available by April 25, as of publication the court has not released a copy.

The Tajik government has only lightly engaged with the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Dushanbe has never acknowledging requests from the world headquarters, based in New York, to send a delegation to meet with government officials. Although meetings with the Tajik ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva have been “friendly,” Lopes said, they have “failed to elicit a response from Dushanbe.”

Two representatives from the Jehovah Witnesses world headquarters were granted a meeting with the deputy chief of mission at the Tajik Embassy in Washington, D.C., in April 2023. “When asked if Shamil will be released on May 16, the [deputy chief of mission] was somewhat optimistic, yet he did not give a definitive answer,” Lopes told The Diplomat. “This made us most apprehensive that Shamil might not be released when his sentence ends.”