On May 9, Sittwe Port on Myanmar’s Bay of Bengal coast received its first shipment of some 1,000 metric tons of cement that was flagged off from India’s Kolkata port five days earlier.

The opening of a shipping line between Kolkata and Sittwe evoked positive comments from both countries, with their governments extolling Sittwe Port’s immense potential.

It will “enhance bilateral and regional trade as well as contribute to the local economy of Rakhine State of Myanmar,” a press statement issued by India’s Ministry of Ports and Shipping said, adding that “the greater connectivity provided by the Port will lead to employment opportunities and enhanced growth prospects in the region.”

At an event marking 75 years of India-Myanmar relations, junta leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing said that the project would bring “more job opportunities for the people of Rakhine and Chin states,” in addition to “regional development.” He said there are plans for a special economic zone at Sittwe too.

The port could bring positive change, but it will be a long time before India and Myanmar will be able to tap its potential.

The India-funded and developed Sittwe Port is located at the estuary of the Kaladan River on the Arakan coast of Myanmar’s Rakhine state. A deep-sea port, it is designed to accommodate vessels with a maximum capacity of 20,000 Dead Weight Tonnage (DWT). But trade between India and Myanmar at present is “way below the capacity of the port,” which could result in the port’s “underutilization,” an official at the Kolkata Port Trust told The Diplomat.

Moreover, given the unrest and instability in Myanmar, and with the Arakan Army in control of swathes of territory in Rakhine state, the development of Sittwe’s hinterland is unlikely to happen in the foreseeable future, as private investors will prefer to stay away.

Importantly, Sittwe Port will have to compete with China’s Kyaukphyu Port, located just around 104 kilometers away, for the limited sea trade coming Myanmar’s way. China is already well ahead of India in this competition. The Chinese port, which is part of the Belt and Road Initiative, is the gateway of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, through which oil and gas are being transported through pipelines across Myanmar into China’s Yunnan province. More recently, Russia too began using this port to transport oil to China.

India’s development of Sittwe Port is aimed not just at using its docking facilities. The plan is to develop alternate access via Sittwe Port to India’s landlocked Northeast.

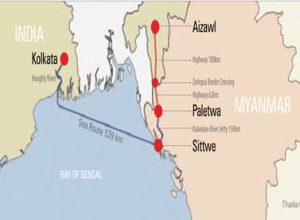

The economic development of India’s restive northeastern states has been hampered by their geography. The region is landlocked. Access to Kolkata Port is via the narrow Siliguri Corridor, which is usually jammed with traffic. Trucks carrying cargo from Aizawl in Mizoram state in the Northeast to Kolkata Port have to run a distance of 1,600 km, which typically takes at least four days to complete. For over two decades now, India has been working on shorter routes to provide its northeastern states with access to the sea.

Sittwe Port is important in this context. It is part of the $484 million Kaladan Multimodal Tranship Transport Project (KMTTP), which envisages connecting Mizoram to Sittwe Port via road and an inland waterway. The project involves the construction of a 109-km-long road between Zorinpui in India and Paletwa in Myanmar, and the dredging of 158 km of the Kaladan River to link Paletwa with Sittwe Port.

Sending goods via the KMTTP is expected to halve transport time and costs.

As I pointed out in an article in The Diplomat in September 2016, while India has big infrastructure-building ambitions in Myanmar, almost every project it has undertaken there suffers from delays and cost overruns. This is the case with the KMTTP too.

India first proposed the idea of the KMTTP to the Myanmar government in 2003. Fifteen years after the two sides signed a framework agreement in 2008, the project is still incomplete.

Construction of the deep-sea port at Sittwe, dredging and modernizing of the Kaladan waterway, and building of the jetty at Paletwa are complete. However, the construction of the India-Myanmar road between Zorinpui and Paletwa is incomplete. India also needs to extend National Highway 54 to reach the Myanmar border. Apparently but for some bridges this stretch is almost done.

Bureaucratic red tape is partly to blame for slow Indian decision-making. Besides, India has had to contend with opposition from local communities and civil society groups. The connectivity corridor also runs through difficult terrain.

However, it is the turmoil in Myanmar that is the biggest stumbling block in the way of the KMTTP. Both Chin and Rakhine states, through which the KMTTP runs, are insurgency-wracked and work on projects has been impacted by the poor security situation in the region. In November 2019, for instance, five Indian workers were kidnapped by the Arakan Army, one of whom died while in the latter’s custody.

The situation has only gotten worse since the military coup of February 2021.

Among the reasons behind India’s support for the Myanmar junta is its infrastructure projects that are underway in Myanmar. Their completion and functioning require security for project infrastructure and workers, which India seems to believe the junta is in a position to provide.

It is not.

The junta is up against a powerful resistance. It is under immense pressure across the country. “In such a situation, there’s no way it will be able to attend to Indian interests,” Angshuman Choudhury, associate fellow at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research, told me recently. What is more, much of the area through which the KMTTP runs is controlled not by the junta but by civilian militias and ethnic armed organizations like the Chin National Front/Army, Chin National Defense Force, and Arakan Army.

Without the support of the Chin groups and the Arakan Army it would be impossible for India to complete the road component of the KMTTP. It will need to engage with the Chin groups and the Arakan Army.

Until they give the KMTTP their nod and support, India’s infrastructure ambitions in Myanmar will remain stillborn.