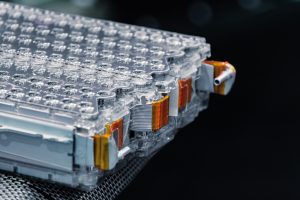

Nearly six months after a $1 billion agreement was signed between the Chinese firms CATL, BRUNP, and CMOC (CBC) and the Bolivian state company Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB) to explore lithium deposits in the South American nation, China has begun extraction. As a public report about the state of the extraction is set to come out later this summer, initially expected in June, China has decided to increase its investment in lithium in Bolivia.

On June 18, the Chinese government announced it would increase its investment by $400 million, a deal that will add to China’s economic standing in Bolivia. China is already the country’s largest trading partner, investor, and financier.

On top of the new investment, the Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank), Bolivia’s largest foreign financier, announced last month that it would be supplying Bolivia with a $250 million loan to help build a zinc refining plant in Oruro, in the heart of mining country. This came after Eximbank in February offered another $350 million loan for the plant, which will be built in part through the Chinese Cooperation Agency and Chinese mining and construction contractors.

Last month also saw China, Russia, and Bolivia announce a new deal, valued at $1.4 billion, to build two new processing plants for lithium carbonate technology. The plants in Pastos Grandes and Coipasa will be run in conjunction between China’s CITIC Guoan Group, Russia’s Uranium One Group, and the YLB. The plants will be neighbors to the plants already being run by the CBC in the Uyuni salt flats.

The $1.4 billion deal was criticized by Western partners and analysts on political and environmental concerns, to which President Luis Arce replied “we are not going to allow political issues to damage the economy of Bolivians.” With Bolivia currently undergoing its worst economic crisis of the 21st century, Arce has promised that Chinese investments, supported by loans, will help deal with the situation.

Laura Richardson, commander of the U.S. Southern Command, visited Bolivia in April to express her interest and concerns regarding Bolivian lithium and the country’s relationship with China and Russia.

Napoleón Pacheco, a professor of economics at the Major University of San Andrés in La Paz, says that the Movement for Socialism, the ruling socialist party of Evo Morales and now Luis Arce, has made the country’s relationship with China its biggest foreign policy and economic priority.

On such a relationship, Pacheco states that “between 2005 and 2018, Bolivia multiplied its exports to China 19 times and its imports 13 times,” while its debt towards China increased over 26 times. José Luis Evia, a Bolivian economist, has listed 28 Chinese companies that have a presence in Bolivia, mainly large, publicly-run companies such as Sinohydro and, now, the three firms that make up the CBC.

Juan Carlos Montenegro, the director of YLB during Evo Morales’ last term, spoke to The Diplomat about his concerns regarding the lithium deals. “I still do not understand how the financing works,” he said by phone. “Their goals are large, but they do not have the raw materials to reach them in the timespan they are claiming.”

Bolivia currently expects to extract 25,000 tons per year from its deal with CBC and wants to reach 50,000 tons per year by 2025. Montenegro argues that the technological capacity of Bolivia’s lithium industry is only sufficient to extract about half of that.

“If this were Argentina or China, this would work, but in Bolivia, the conditions are different,” he said. He added that Bolivia will need to develop new technologies to meet its extraction, production, and recuperation goals, and does not see those achievements coming until 2025.

Other critics say that Chinese operations in Latin America’s mining belt have been environmentally damaging and disrespectful of indigenous concerns. The Collective on Chinese Financing and Investments, Human Rights and the Environment looked at 26 mining, infrastructure, and energy projects in Latin America. It concluded that every single one of them had contributed amply to deforestation and water pollution and human rights violations against local and indigenous communities.

A report by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights published this March also found that 14 Chinese energy and mining projects in nine Latin American countries “ignored regulations protecting the environment and local and Indigenous peoples.” Even nationally, Chinese mines have been plagued by safety disasters, with repeated cases of mining explosions, landslides, and environmental contamination.

Furthermore, according to surveys from some Bolivian think tanks including the Center for Studies for Labor and Agricultural Development in La Paz, the increased Chinese presence has created social, political, and cultural tensions between new Chinese workers and Bolivian locals.

“They do not attempt to learn Spanish or eat with us, they keep to themselves and live in their own facilities,” said one anonymous worker at a Chinese-run construction site. Another complained about Bolivia being used for “political games” by China, as “they only care about their own interests, not the damage they are doing to our country, they are just like the Americans or the Spanish before them.”

Montenegro, who now works as an energy and mining consultant, said that these issues were not unique to Chinese projects. “This is not a Chinese problem, everyone has to deal with this,” he said, adding, “where there is capital, there is development, we just have to be careful to respect sovereignty and establish the rules of the game to ensure our rights are protected.”

But the Chinese government, local sources working with Chinese public companies in mining and infrastructure say, has attempted to suppress these concerns and made workers sign non-disclosure agreements to ensure they do not discuss the Chinese companies’ conduct at the work sites.

The latest agreement reflects China’s ambition to become the principal investor in Bolivian mining, a country with large reserves of lithium, zinc, cobalt, silver, and gold. China is reportedly prioritizing Bolivia in the so-called “lithium triangle,” which also includes Argentina and Chile, given the greater level of political-economic leverage that it enjoys there.

Bolivia must be wary of China’s intentions and ambitions in the country, and provide further oversight to minimize political, cultural, economic, and environmental damage. It should also share information openly with the Bolivian public about the dealings with Chinese firms to increase confidence, while ideological quarrels with Western countries should be dropped to ensure a diversified, robust economy at a time when it is most needed.