Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has triggered an unprecedented reshuffling of Eurasian geopolitics, and Central Asia is a testbed for emerging strategic shifts. A number of external powers are vying for influence in the region, and the EU is definitely one of them.

Could Central Asia become a battlefield between China and the West? In particular, could it add to a growing list of frictions between an increasingly assertive Beijing and an increasingly geopolitical EU?

Central Asia’s Patchwork

Sino-European relations in Central Asia can only be gauged in the complex context of the region.

Amid the war in Ukraine, Russia’s image in Central Asia has deteriorated considerably, but it would be a mistake to assume that Moscow’s sway over the region has fizzled out. Russia remains an important security and economic actor and has plenty of levers at its disposal. Moscow’s trade with Central Asia rose by 20 percent in 2022, while Russia’s labor market accommodates millions of Central Asian workers, with remittances from Russia accounting for more than 30 percent of GDP in Tajikistan and in Kyrgyzstan.

Just as importantly, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan host Russian military bases and facilities, and rely – even if reluctantly – on Moscow’s security umbrella as part of the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Tellingly, Kazakhstan’s government requested a CSTO “peacekeeping operation” to respond to clashes in January 2022. Continued Russian influence was on full display when all five Central Asian leaders flew to Moscow for the May 9 Victory Day parade.

The fallout of Russia’s military debacle in Ukraine allows China to make further inroads into Central Asia, but Beijing is cautious not to step on Moscow’s toes – or, rather, not to be seen as doing so. Apart from the Sino-Russian “no limits partnership,” officially declared on February 4, 2022, China and Russia are the main pillars of an expanding Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a large entity sprawling across Eurasia.

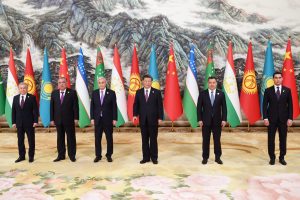

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a key Chinese narrative in Central Asia, backed up by a long list of China-financed projects in the region. Discussions about the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway and, despite reliability concerns, Line D of the Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline are the latest reminders that the BRI is alive and well in the region – despite controversies surrounding Beijing’s flagship megaproject in other parts of the world. The May 18-19 summit in Xi’an amply demonstrated China’s growing influence in Central Asia.

China’s trade with the region was worth $70 billion in 2022. By the end of the same year, the stock of China’s investments in Central Asia amounted to nearly $15 billion, though it is less clear to what extent this is genuine FDI or the worth of construction projects based on Chinese loans and contracts merely executed by Chinese companies. Business contacts are considerably facilitated by visa-free travel regimes established between China and several governments in Central Asia.

While treading carefully in the region, Beijing has ramped up its cooperation with Central Asian armed forces, as well as with their military and intelligence agencies. China has deployed private security companies to guard Chinese investment projects in Kyrgyzstan, and Chinese paramilitary police units have been policing Tajikistan’s borders with Afghanistan.

By and large, Central Asian states view China as a political heavyweight and an indispensable economic and political actor. Tellingly, on a number of occasions Central Asian countries have supported China on “sensitive” U.N. resolutions or have meticulously avoided confronting Beijing. At the same time, Beijing’s soft power campaign in the region is less successful. China appears to be popular primarily with political and business elites, but much less so with Central Asian societies.

Turkey is also a factor to be reckoned with. Not only does it retain cultural bonds with four out of the five Central Asian nations, but a large number of Turkish companies are active in the region. The significance of the Middle Corridor, running from Central Asia toward the Caspian Sea and Turkey, is often pointed out amid the ongoing war in Ukraine and shrinking traffic on the railway track through Kazakhstan and Russia. The Turkey-led Organization of Turkic States, too, could well grow into yet another vector of Central Asian nations’ foreign policies.

Europe’s Weight in Central Asia

The EU claims a prominent position in the region thanks to its economic pull as a major trading partner – in 2022, the trade volume between the EU and Central Asia was worth some $52 billion. Above all, the EU and individual members states collectively are the biggest source of investment capital for the region: in 2022, the EU accounted for more than 42 percent of the total FDI stock in Central Asia, compared to 14.2 percent for the U.S., 6 percent for Russia, and a meager 3.7 percent for China. Meanwhile, the EU has started promoting Global Gateway projects for connectivity between Central Asia and Europe.

Squeezed between Russia and China, all Central Asian states wish to diversify their international partnerships in a quest for increased bargaining power. The EU is an obvious option to consider. The changing geopolitical situation created by Russia’s war in Ukraine puts wind in the sails of the EU and provides it with an opening to play a more active role in the region – hence the flurry of high-level visits by EU officials to Central Asia over the past year or so.

Not least of all, the EU’s soft power definitely is an asset, in terms of educational and professional opportunities, living standards, lifestyle, etc. Despite numerous Chinese scholarships granted to Central Asian students, a half-an-hour talk with youngsters in the region will show that Europe – and the West at large – is their primary choice.

For all that, the EU’s aid to the region is not sufficiently visible and, therefore, not fully appreciated. A new catchphrase, “strategic communication,” has now become all the rage in Brussels, but it remains to be seen to what extent this drive will be successful in Central Asia.

Prospects of China-EU Relations in Central Asia

The following trends are likely to be observed down the road. Like China, the EU will remain primarily a major economic partner of the region. The EU certainly cannot be a security broker, let alone a security guarantor, in Central Asia. At best, the EU can contribute to the overall economic security of the region, though this is not insignificant.

Second, Europeans are highly unlikely to have a headlong clash with China in Central Asia. The EU is at loggerheads with Russia over Ukraine, but not with China. Central Asia will not become a geopolitical battlefield between the EU and China, as they have other fronts of serious disagreement. For instance, China’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang – involving not only Uyghurs but also ethnic Kazakhs and Kyrgyz – have been a thorny issue. The EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment has been frozen. Taiwan is also becoming an increasingly prominent theme in internal debates in European capitals and the needle definitely is moving toward the “rivalry” component in the EU’s triple definition of China. However, for the time being these issues are unlikely to spill over EU-China relations in Central Asia.

Yet fierce Sino-European economic competition should be expected in a number of sectors, including natural resources and technological transfers. While European countries are willing to transfer industrial technology to the region, China is already very active in this field. There are some 60 Chinese industrial transfer programs for Kazakhstan and a similar number of projects in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

Europeans rightfully claim they are the biggest donors and investors in the region, bigger than China. The EU is held in high esteem as a source of cultural and social attraction, but it needs to be more engaged in addressing key challenges in the region. And Europeans will have to tell their story properly, through much more effective “strategic communication,” as a response to Chinese narratives promoted in Central Asia. Back in 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 outbreak in Europe, Josep Borrell coined the term “battle of narratives.” A true “battle of narratives” between the EU and China is likely to become more manifest in Central Asia over the years to come.