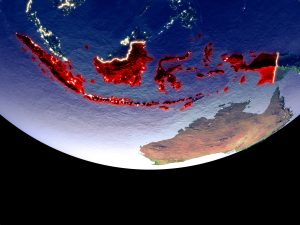

Indonesia is strategically located in Southeast Asia, with a vast archipelago stretching between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Its location makes it a critical maritime hub, connecting major shipping routes between Europe, East Asia and Australia. This gives Indonesia significant geopolitical importance and makes it a focal point for regional and global interests. Indonesia’s strategic location, however, also places it in a challenging position as China-U.S. rivalry intensifies.

For a very long time, Jakarta has preferred to avoid taking sides in great power rivalry, advocating neutrality instead when engaging major powers. A critical question is whether neutrality is sufficient to ring-fence Jakarta’s interests in the event of a China-U.S. military conflict.

Will Indonesia suffer the same fate as Belgium during World War I? Belgium’s neutrality did not guarantee security; instead, its strategic position led Germany to violate and occupy its territory. Similarly, the warring parties in the Vietnam conflict ignored Cambodia’s neutrality during the Cold War. Cambodia’s strategic location pulled it into great power conflict as American and Vietnamese forces fought battles inside its territories.

To set the geographical context, Indonesia is caught between military build-ups by China and the United States. Indonesian defense officials privately express concerns that military development in the north and south of the country could threaten Indonesia’s security and stability in the long run.

To the north, China is attempting to turn the South China Sea into its internal lake, building several man-made islands equipped with runways and military installations to sustain a continuous Chinese air and naval presence in the region.

The South China Sea has always been a critical concern for Indonesian defense planners, given that it is a key northern approach to the Indonesian archipelago. U.S. archival documents reveal Indonesia improved its military infrastructure, from radar to runway extension, around the Natuna Islands at the southern edge of the South China Sea during the 1980s in response to the Soviet Union’s increasing air and naval presence in the region.

The significance of the South China Sea to Indonesia’s security continues until today. While Indonesia is not a claimant state in the maritime and territorial disputes involving Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam, its maritime boundaries and exclusive economic zone (EEZ) are affected by the tensions in the region. Chinese fishing vessels, shadowed by Chinese navy or coast guard vessels, continue to operate illegally within Indonesian waters around the Natunas.

To the south, the United States has been stepping up its military presence in Australia to counter China. In July 2023, Australia and the U.S. announced an increased U.S. rotational presence in Australia, including frequent U.S. submarine visits in Western Australia, more access to Australian air bases for U.S. air assets, and plans to pre-position U.S. military stores and materials in Bandiana, Australia. This announcement came a few years after Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States announced AUKUS, a security partnership to counter China’s aggressive moves in the Indo-Pacific region centered around the provision of nuclear submarines to Australia.

Geographically sandwiched between the South China Sea and Australia, Indonesian defense officials privately acknowledge Indonesia’s strategic challenges. They expressed concerns that Indonesia could unwittingly be drawn into great-power military conflict due to its strategic location, especially should military forces from the warring parties engage each other within the Indonesian archipelago.

Several Indonesian defense officials privately pointed out that China’s military installations and assets in the South China Sea are strategic threats to Indonesia’s security as well as high-value targets in any China-U.S. military conflict. They assessed that the Chinese are keen to use the South China Sea as part of China’s second-strike capability against the United States in any nuclear confrontation. Thus, the U.S. will be interested in blunting this capability.

Additionally, these Indonesian officials believe that any U.S.-led military operations against Chinese military assets in the South China Sea would likely involve the Americans (and its allies) transiting through the Indonesian archipelago from Australia. One senior Indonesian naval officer privately pointed out China would probably include such a scenario in its planning and may choose to engage U.S.-led forces in the Indonesian archipelago.

Any China-U.S. military clashes in the Indonesian archipelago will turn the region into a graveyard. However, Indonesia will endure the most collateral damage. Most of Indonesia’s domestic and international trade is handled via sea routes. Thus, any military clashes within the Indonesian archipelago will likely hamper the movements of goods and people between some of the more than 17,000 Indonesian islands and impact Indonesia’s international trade. Furthermore, any destruction involving nuclear submarines will have devastating economic and environmental consequences for the Indonesians, a key concern expressed privately by some Indonesian defence officials.

History shows that strategic location, not neutrality, plays a more significant role in determining a state’s security during military conflicts involving major powers. Jakarta will have to consider this factor as China-U.S. rivalry intensifies. It is also in the interest of Indonesia’s friends, such as Australia, to aid Jakarta in moving away from neutrality should the Indonesians choose to do so when the time comes.