In recent years, a host of studies have analyzed instances of coercion from China, with a particular emphasis on Beijing’s punitive economic measures. Frequently cited examples include China’s restrictions on Australian wine, Norwegian salmon, and South Korean tourism after their respective governments drew the wrath of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership. While this coercion has been shown to negatively impact target countries’ companies or economic sectors in the short term, the general consensus of scholars is that China’s coercion has not effectively altered the policies or positions of targeted countries.

However, new analysis of data from the 2022 China Index suggests that coercion is more effective than previously thought.

The 2022 China Index is a project published by Doublethink Lab that collects observations on China’s influence in 82 countries. Influence scores are calculated via 99 Indicators, developed by a committee of experts on Beijing’s foreign influence strategy. The influence tested by each Indicator is categorized by type into “exposure,” “pressure,” and “effect.” Exposure Indicators test for the presence of vectors, like trade dependencies, through which Beijing can translate influence. Pressure Indicators examine efforts by China to execute coercive diplomacy. Effect Indicators measure the extent to which countries have taken actions favorable to China’s interests. The total scores for each category are computed for each country to produce rankings. Further information about the project’s methodology can be found on the China Index website.

Controlling for Wealth

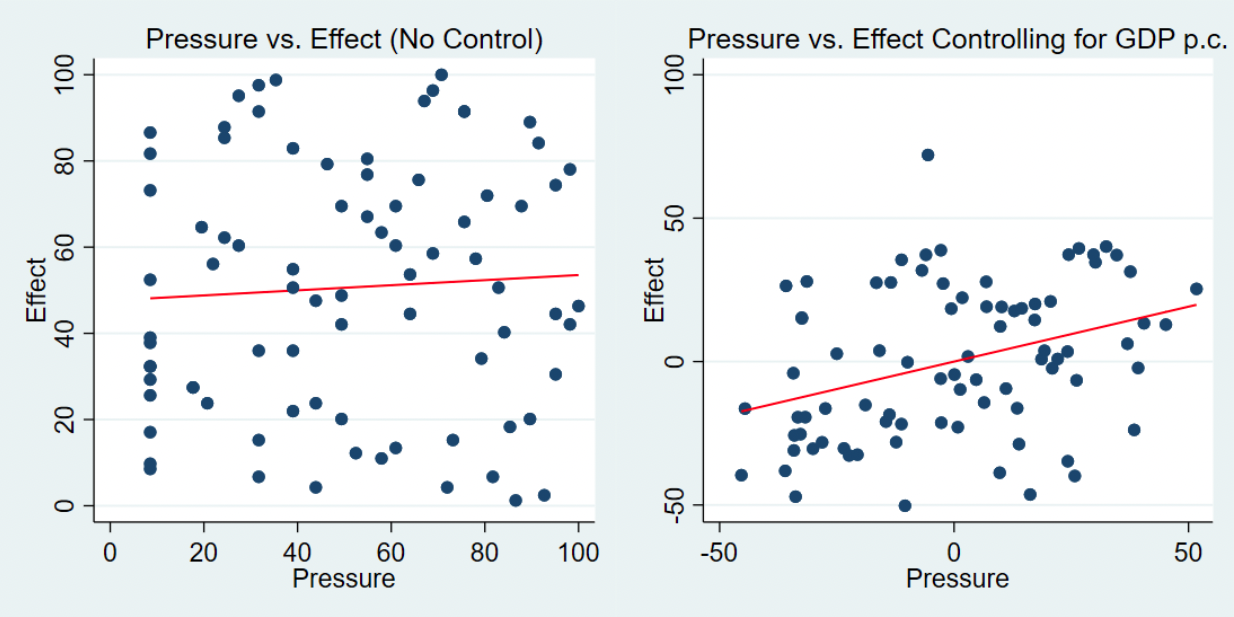

The key breakthrough from this data comes from controlling for GDP per capita (a measure of a country’s wealth) when conducting statistical analysis on the relationship between China Index pressure and effect scores. A simple correlation analysis indicates there is no relationship between the two, in line with previous findings (including past research from Doublethink Lab). However, when controlling for GDP per capita (in other words, factoring out the role that national wealth might play in mitigating pressure from Beijing), the China Index data reveals that China’s pressure does correlate with observed effect. In other words, pressure works but is mitigated by greater wealth, which brings with it increased capacities.

Failing to control for GDP per capita obscures the relationship between pressure and effect, because wealthy nations are simultaneously the most likely to be pressured by Beijing and the least likely to produce policies or outcomes favorable to China. The data shows that to achieve a desired level of effect, China has to apply far more pressure to a rich nation than a poor one.

As the graphs above show, correlation between “pressure” and “effect” emerges when controlling for GDP per capita.

This result raises two questions. First, if pressure works, and far less of it is needed to bully desired results out of developing states, why doesn’t Beijing employ this tactic on poorer states more often? Second, how does higher GDP per capita insulate nations from the effects of China’s pressure?

Asymmetry and Capitulation

In response to the first question, an answer may simply be that Beijing generally doesn’t need to use pressure to achieve its goals in developing states. China is the biggest sovereign lender to developing countries, and according to the International Monetary Fund, many of these countries are or may soon be in debt distress. Many developing nations have also received significant investment through China’s Belt and Road Initiative or Global Development Initiative. These countries may intuitively understand that they shouldn’t bite the hand that feeds them, and naturally follow China’s policy lead.

A prime example of this was the U.N. Human Rights Council motion to debate China’s treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Developing countries fell in line to defeat the proposal 19-17, with 11 states abstaining.

It is worth noting that in the rare cases where China has applied significant pressure to low-income states, they appear to bow to Beijing’s demands. A recent Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) report ranked the outcome of eight instances of Chinese coercion as a “Win,” “Mixed Win,” “Mixed,” “Mixed Loss,” or “Loss” for China. While no instance was classified as an outright “Win,” there were two “Mixed Wins,” involving Mongolia and the Philippines – the only two developing economies considered.

Wealth Against Pressure

In explaining how high GDP per capita ameliorates pressure, multiple factors are certainly at play, but I will focus on two. First, Beijing generally holds less leverage over high GDP per capita nations, which often provide goods essential to China’s own development. China has far more leverage over Mongolia, from which it imports relatively replaceable raw materials and animal products, than it does over the United States, which furnishes China with critical technologies.

Furthermore, GDP per capita is correlated with democracy and low corruption levels among the 82 countries in the China Index dataset. When China lashes out at a country with independent media in the liberal democratic vein, local public sentiment tends to turn against Beijing, damaging its long-term objectives. This was seen during the tussle over South Korea’s deployment of the THAAD missile defense system, which resulted in plummeting public opinion among South Koreans toward China.

In countries with state control over media, coverage of Beijing’s coercion may be suppressed to avoid further worsening the relationship. In effect, this grants China a free pass for coercion. Thus, fostering a healthy independent media can act as a bulwark against coercive practices.

Given the limited number of incidents in which China has pressured low-income states, doubt may remain as to whether Beijing’s brand of coercive pressure really does work. In the search for more case evidence, major international corporations operating in China may serve as an effective proxy. Similar to low-income nations, the balance of power in their relationships with China is extremely skewed toward Beijing, but these companies are targeted much more frequently. In most cases in which these corporations experience coercion from China, they capitulate. Based on data collected by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), 82.7 percent of companies issued apologies, complied with directions, or both, in the face of Beijing’s coercion.

Conclusion

Many of the studies conducted on China’s coercion (such as those by the CSIS or the European Parliamentary Research Service) have identified promising counter-strategies to such tactics. However, these studies also assert that Beijing’s coercion on the whole is ineffective, leaving politicians wondering why they should develop countermeasures for a problem that might not really exist.

The data presented above shows that China’s coercion is indeed effective, only that it is mitigated when states are wealthier on a per capita basis. Therefore, policymakers around the world, especially those representing countries with lower average incomes, must be proactive about developing mitigation strategies for pressure from Beijing. Given that incidents of China’s coercion are on the rise, a sense of urgency must be restored to lawmakers’ efforts to build an effective framework to combat these tactics.