For the second time in 2023, the Labor government in Queensland has brought in legislation they admit is incompatible with the state’s Human Rights Act. This time, the law– introduced by Minister for Police, Fire, and Emergency Service Mark Ryan with little oversight or warning – will allow children to be imprisoned in police watch houses (the equivalent of jails in the United States).

Queensland is the only state in Australia that does not have an upper house of its parliament, which results in less judicial oversight for legislation when a political party has a majority in the lower house.

And just like the previous instance of human rights breach, it will be children – particularly First Nations children – who will bear the brunt of the inhumane and unnecessary legislation.

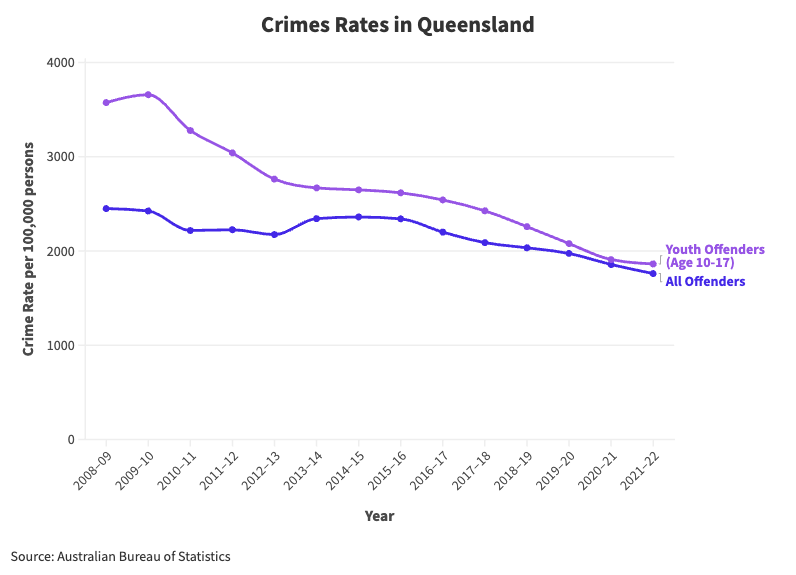

There has been a media blitz – in a state with only one major newspaper – against a supposed “crime wave” throughout Queensland. Statistics show a different story, with both youth and adult offenders in 2021-22 (the latest available data) at their lowest level in a decade. The rate of unique youth offenders fell by 31 percent since 2012-13.

However, the rate of actual crimes rose 8.1 percent, which has been part of the basis behind the government’s crackdown, described as a “race to the bottom” by critics.

Queensland’s Human Rights Commissioner Scott McDougall said Queensland was setting a “dangerous precedent.”

“These changes are rash, alarming, and will not reduce youth crime or make the community safer,” he said.

“Allowing children as young as 10 to be held indefinitely in what are essentially concrete boxes means there are farm animals with better legal protections in Queensland than children.”

Change the Record national director, Gunggari campaigner Maggie Munn, said the decision had outraged Aboriginal, Human Rights and legal groups throughout the country.

“This is now the second time Queensland has suspended its human rights act to criminalize and punish children in this state. Incarcerating children whether in prisons or watch houses is harmful, the government knows this and yet continues to enforce these conditions,” they said.

“The Palaszczuk government has demonstrated a dangerous and prolonged track record for disregarding parliamentary process and violating human rights that is unprecedented in Australia. All Australians, regardless of where you live, should be alarmed by this government’s actions that undermine our fundamental human rights.”

The amendments to the legislation come in the wake of the Queensland Supreme Court ordering the urgent transfer of three children out of detention in police watch houses, after the government admitted that they had no legal basis to detain them.

The amendments also permit the government to hold children in adult prisons, a new practice that is widely condemned and discouraged. Experts argue that housing children in any prison – let alone an adult facility – will only lead to recidivism and long-lasting trauma.

Earlier this year, a Queensland magistrate expressed grave concern about children in watch houses. They noted watch houses contained “adult detainees [who] are often drunk, abusive, psychotic, or suicidal” A report by the Queensland Family and Child Commission last year found Aboriginal children had been incarcerated in Queensland watch houses for up to 35 days.

In June, the Youth Advocacy Centre said they had seen examples of children pleading guilty to crimes they hadn’t committed in order to avoid spending time in detention.

Documented concerns of watch houses include a lack of appropriate facilities for girls, lack of access to showers, and clean clothes.

“This is the second time the Queensland Labor Government has bypassed the Human Rights Act so it can lock up more kids, predominantly First Nations kids,” Michael Berkman, a state Greens MP, told The Diplomat.

“We know what solutions would actually rehabilitate kids and reduce crime, and they don’t include keeping children alongside adults in prisons and watch houses,” he said.

“The Government needs to wake up, listen to the experts and properly fund public services, early intervention and community-led diversion programs, or there will only be more harm and more victims in Queensland.”

In a statement, Commissioner Natalie Lewis and Principal Commissioner Luke Twyford of the Queensland Family and Child Commission said the children who were being locked up were by and large the “most marginalized and vulnerable and who need our help.”

“Upholding the human rights of children in conflict with the law does not disregard the concept of accountability; it simply means that consequences should not cause further harm to anyone,” they said.

Labor MPs were skeptical of the legislative amendments but were told that the changes were necessary in order to avoid a legal challenge that could see children transferred out of police custody and into youth detention centers, many of which are overcrowded.

“It would have meant every child went to the youth detention centers, and clearly that is a capacity issue, which we had not foreseen,” the youth justice minister, Di Farmer, said.

However, submissions seen by The Diplomat from human rights groups show that in 2021, when a law was passed removing the presumption in favor of bail for some children, the state government was made aware that it would likely lead to overcrowding of the detention centers, as well as almost certainly leading to recidivism and “increase the risk of reoffending.”

An open letter signed by nearly 200 human rights, legal experts, and academics as well as the former commissioner of Queensland Corrective Services condemned the Queensland government’s policies.

In part, the letter reads:

Queensland’s new watch house laws categorically violate children’s rights and further exacerbate the human rights emergency in Queensland’s already broken youth justice system that disproportionately affects Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Although around 8% of 10-17 year olds in Queensland are First Nations, at least 65% of the Queensland youth prison population on an average day are First Nations children.

Debbie Killroy is CEO of Sisters Inside, a group advocating for the rights of women and girls currently incarcerated. She argues that children are being used as political pawns “where adults in power can use them to perpetrate harm.”

“The legislation that allows the prolonged caging of children in watch houses and adult prisons will ensure harm for all the children and the community for generations to come,” she said.

The Queensland government, led since 2015 by Annastacia Palaszczuk, has so far stood firm on their decision, in part backed up by an opposition and state media who seemingly don’t think any decision regarding incarcerating children is going far enough. Despite the criticism, the government’s decision earlier this year to criminalize bail breaches for children remains.

Of the 169 children who were arrested on these new charges, 112 were Aboriginal – many from the most marginalized communities in the country. Despite making up only 5 percent of the child population in Queensland, First Nations children comprise 62.6 percent of the youth prison population. Many are the victims of abuse, homelessness and sexual assault. Others have been born with fetal alcohol syndrome.