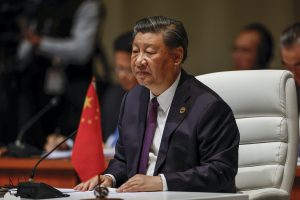

In the security state that Chinese leader Xi Jinping is building, economic security matters. But in the “securitization of everything” that is emblematic of his governing style, how crucial is it exactly?

Economic security is just one of the 16 areas outlined in Xi’s 2014 vision of “comprehensive national security” (总体国家安全). This concept encompasses a broad range of issues, from culture to “ecological security.” When he first introduced the notion at the founding session of the Central National Security Commission, Xi Jinping called economic security the “foundation” of China’s comprehensive approach. As such, it ranked below the “bedrock” (根本) of “political security,” which centers on preserving China’s regime stability.

Among the other elements listed, military and technological security are meant to provide an “assurance” (保障) to that overarching goal. The remaining domains, such as deep sea and space, are areas where the party-state aims to defend Chinese interests from threats.

China’s “comprehensive national security” concept was first articulated during a critical juncture in Xi Jinping’s first term at the top of the Politburo Standing Committee, when his national security prioritization started becoming obvious. Since then, China’s international environment has considerably deteriorated, largely as a result of pushback against Xi’s policies. A factor behind this deterioration is the rise of economic security agendas in the United States, Japan, Europe, and South Korea, which complicates Chinese national and corporate strategies to expand internationally.

Most countries’ strategies do not explicitly mention China, a fig-leaf approach referred to by the EU as “country-agnostic.” The United States uses the designation “foreign countries of concern” (China, North Korea, Iran, and Russia), saying its goal is to ensure “malign actors do not have access to cutting-edge technology that can be used against America and our allies.”

Whether these policies openly state it or hide it behind diplomatic language, they all respond to the same risks: China’s excessive leverage resulting from its investment in critical infrastructure and its importance in many supply chains, which creates options for economic coercion or the restriction of access to critical raw materials; leakage of civilian technology that ends up in military projects; and a list of issues linked to an uneven playing field with China’s state-led economy, and its powerful industrial policies.

Economic security is hotly debated in the European Union. Some argue that by securitizing economic relations with China, the European Commission is gaining excessive power at the expense of EU national governments. Others criticize an overly defensive posture, with risks for the European single market, and question the extent to which the Commission’s agenda is driven by the United States.

By contrast, there is little public debate in China about the notion, except in the area of supply chain resilience. Naturally, no one can contest the absolute priority placed on “political security” and the designation of “economic security” as a tool for achieving it. Framing “economic security” from the outset as it relates to regime stability sidesteps questions raised in the West, especially the central difference between a narrower EU approach prioritizing military technologies, coercion, and excessive leverage versus a broader approach favored by the United States and Japan, centered on economic competitiveness.

Xi’s absolute priority on national security reflects the Chinese Communist Party’s assessment that the “period of strategic opportunity,” previously emphasized by all Chinese leaders since Deng Xiaoping, has now come to an end, replaced by a period of “changes unseen in a century.” In Xi’s “New Era,” one might add that the top priority has shifted from the prosperity of the Chinese people to a quest for state power on the global stage.

With clearly established strategic priorities, the space for policy debate lies in how to pragmatically implement efficient policies. China undoubtedly faces supply chain challenges, brought to light by U.S. semiconductor restrictions. The solution to this? “Vertical integration,” where major market players leverage their size to build a self-reliant supplier network, or at least one with reduced disruption risks. Here, companies are the implementers of a strategy designed by the party leadership. In addition, Chinese views seem to favor public stockpiling of critical raw materials, an approach often dismissed in Europe as a costly waste of resources.

When it comes to relations with the EU, Chinese commentaries depart from “de-risking is just decoupling in disguise” line, as goes a now famous Xinhua commentary. Since 2022, there has been a flurry of diplomatic activity to numb the European de-risking agenda. This effort culminated with the Germany visit of Chinese Prime Minister Li Qiang, who in the presence of German top companies executives, rejected “de-risking” and called for all parties to adopt instead a “dialectical view of dependence,” meaning “one should refrain from exaggerating ‘the degree of dependence’ or even simply equating interdependence with insecurity.”

The message here is that the two sides are able to co-manage the dependence risks they pose to each other. What goes unmentioned is the asymmetry in the decision-making process that leads to imposing costs – China under Xi Jinping has a well-established record of economic coercion, while the EU anti-coercion instrument, newly adopted in October 2023, requires the exhaustion of all diplomatic options before the EU can resort to defensive retaliatory measures.

Chinese signals are somewhat contradictory. On the one hand, China uses top foreign leaders’ visits to Beijing to secure public statements against decoupling. On the other hand, China welcomes the European rejection of decoupling, and focuses on managing the concrete challenges that the EU’s de-risking policies will continue to pose to China-EU interactions. There seems to be an understanding that European moves are rational and justified. After all, Europe remains incredibly more open to China than the opposite.

In sum, China seeks to minimize the European “de-risking” agenda while also promoting its own national-security-first approach in China-EU trade and investment relations. This is essentially what the Chinese ambassador to the EU, Fu Cong, said when he argued that “in our view, dependency is not dangerous. What is dangerous is to weaponize the dependency. If the EU has the political will to alleviate their concerns, China is ready to talk to them and come to some sort of agreement. We should not weaponize the dependencies that one side may have on the other.”

China, however, has a proven track record of weaponizing dependencies and is also rushing to reduce its own reliance on foreign suppliers. While Fu’s statement may be insufficient to build trust, it nevertheless has the merit of underlining China’s diplomatic tactic of downplaying the problem.

This article was originally published as the introduction to China Trends 17, the quarterly publication of the Asia Program at Institut Montaigne. Institut Montaigne is a nonprofit, independent think tank based in Paris, France.