China-U.S. relations are once again having a moment. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s recent visit to the United States produced several meetings, including with President Joe Biden and California Governor Gavin Newsom. Sports re-emerged as a potent element in China-U.S. relations, as Xi appeared genuinely pleased to receive a gift of a basketball jersey (with the lucky number 8) from Newsom.

It’s constructive that the two sides are talking again. Climate change is a shared threat that demands cooperation between the world’s two largest polluters. Moreover, with constitutional democracy facing complex threats from multiple vectors, the West requires performance legitimacy from economic growth – just as Beijing needs trade and investment from the West to mitigate its own metastasizing economic risks. Despite nascent warming ties on trade and climate, however, constitutional democracies shouldn’t forget the highly malign role Beijing has played throughout Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

China’s Pro-Russia Neutrality

Evan Medeiros, the former top adviser to President Barack Obama on the Asia-Pacific, was the first to characterize Beijing’s alignment with Moscow in the context of the invasion of Ukraine as “pro-Russia neutrality.” Conversely, a November 12 article by a Chinese expert on Sino-Russian relations in The Diplomat recently argued that Beijing has not chosen sides in the conflict.

A review of the history of the conflict shows that Medeiros’ framing remains accurate. While Beijing is not a combatant in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and does not appear to have provided Russia with direct military assistance, its informational, economic, and logistical support for Moscow has been substantial and potentially even decisive.

Beijing’s pro-Russia neutrality began before the invasion, when it sought to undercut Western warnings about the looming dangers of Russian aggression. Through various methods, including a November article series published in the authoritative People’s Daily, China attempted to undermine the credibility of Western (especially U.S.) intelligence services, just as Western warnings of a potential impending invasion became public.

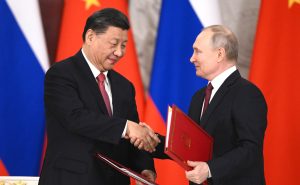

It’s unclear if Russian President Vladimir Putin ever informed Xi of his plans to invade Ukraine. There is, however, significant public evidence that Moscow signaled to Beijing it would not invade Ukraine during the Beijing Winter Olympics. In mid-January, Russia and Belarus announced they would hold combined military exercises along the border of Ukraine, but would not conclude them until February 20 – the last day of the Olympic Games. The timing of the exercises suggested that Moscow would not conduct an invasion during the Olympics, which would have posed major dilemmas for Beijing.

Beijing saw several indications suggesting an imminent military action. It may even have been tipped off by Putin himself, or by its intelligence methods and sources within Russia. Still, China not only dismissed Western warnings of an invasion, but actively tried to undermine them.

It’s impossible to know how much Beijing’s denial and obfuscation impacted the course of the war, but it may have influenced the initial phase. Ukraine’s leadership was publicly skeptical of the dangers of a full-scale invasion and was slow to mobilize for conflict. To be clear, Kyiv’s reluctance to mobilize was overwhelmingly due to domestic political reasons. Still, Ukraine’s leaders may have potentially been influenced, in part, by Beijing’s dismissal of the risks of conflict.

Ukraine’s slow mobilization nearly resulted in disaster, as Russia’s attempt to decapitate the Ukrainian leadership was only very narrowly averted at the Battle of Hostomel Airport on February 24. Ukrainian National Guard conscripts fought a successful delaying action against elite Russian airborne troops long enough to prevent what could have been a disaster. Beijing’s messaging could have played a role – at the margins – in slowing the Ukrainian leadership’s appreciation of the looming dangers of an invasion, raising the probability of a successful Russian decapitation strike on Ukraine’s political leadership.

China’s Semi-overt Support for the Russian Invasion

While Beijing’s anti-U.S. information campaigns played an uncertain but potentially important role in downplaying the threat of an invasion before February 24, other forms of pro-Russia neutrality have been more open. Although China has largely complied with the substance of Western sanctions, it has also clearly assisted Moscow via semi-overt means throughout the conflict.

In the early days of the conflict, the Chinese Foreign Ministry amplified the Kremlin’s baseless claims about biolabs operating in Ukraine; it also blamed the West for the conflict. Beijing and Moscow have enjoyed significant success in shaping the information environment and shifting blame for the conflict and its consequences.

China’s pro-Russia neutrality has also taken on concrete dimensions, via its provision of critical dual-use goods to Russia. As my colleagues at the Atlantic Council and I reported in recent research, China’s exports to Russia of vehicles, drones, parts for tanks and fighter jets, and electronic components have played a major – potentially decisive – role in helping Russian forces avert a military disaster in Ukraine.

Chinese exports to Russia of trench-digging equipment have helped Russian forces stymie Ukrainian advances. As Ukrainian forces began to push back Russian troops in August and September of 2022, Russian forces began to entrench themselves and constructed the “Surovikin Line” of defensive fortifications. Russia’s construction of a series of trench networks in Ukraine coincided with a major increase in imports from China of construction equipment, such as excavators and front-end shovel loaders.

Chinese excavator exports to Russia more than tripled in September 2022 when compared to September 2021, while a Wall Street Journal investigation found that some Chinese-made excavators were shipped directly to the front lines. Furthermore, Russia’s elevated imports of construction equipment largely occurred outside of its civilian construction season and has declined following the start of Ukraine’s counteroffensive in June 2023, suggesting that there was a non-civilian dimension to the shipments.

Chinese exports of construction equipment helped entrench Russian forces, potentially preventing a military and political disaster for the Kremlin and prolonging the conflict.

China’s direct exports to Russia of other dual-use goods, such as drones, parts for tanks and fighter jets, trucks, and electronic components, have also played a major role in facilitating the invasion. Other analyses show the importance of transshipments or indirect Chinese exports to Russia, as Chinese shipments nominally headed to Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and other places are in fact very likely re-exported to Russia.

China’s direct and indirect exports to Russia do not necessarily violate Western sanctions – and are very difficult for Western policymakers to stop. As Marc Cancian and other analysts have noted, however, it is a near certainty that Beijing is aware of the shipments. While the Chinese Communist Party enjoys nearly untrammeled authority within China, it has done little to nothing to stop the export of dual use goods to Russia that technically do not violate sanctions but also demonstrably aid the Kremlin’s war effort.

Don’t Lose Sight of the CCP’s Character

The West’s relationship with Beijing has always been complicated and is only becoming more so. On the one hand, the constitutional democracies should enhance ties with China on trade and climate, among other issues, whenever possible and appropriate. At the same time, the West should be clear-eyed about the limits of its relationship with Beijing, which has chosen the side of the aggressor in the deadliest conflict in Europe since World War II.