Two months ago, I was in Taiwan where, among other people, I met two Taiwanese men who spent time in Chinese prisons. Their stories serve as a warning of the potential fate for Taiwan itself if Xi Jinping decides to take the island.

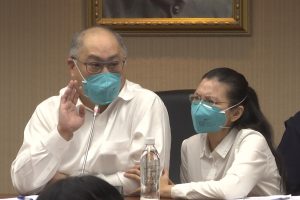

Lee Ming-che was sentenced to five years in jail in China in 2017 and returned home in April 2022. Lee Meng-chu (also known as Morrison Lee) was arrested in 2019, and only returned home to his family in Taipei three days before we met.

Lee Ming-che is a long-time human rights activist. He supported Chinese political dissidents financially, and disseminated information about universal human rights and democracy online to mainland Chinese audiences. For these activities, he was accused of “subversion of state power” and spent five years in prison in China.

Lee Meng-chu was a businessman who attended one of the protests in Hong Kong in 2019. He was caught at the border-crossing into mainland China in Shenzhen with postcards promoting “love, peace, compassion and communication,” and flyers that said “Hong Kong and Taiwan stand together.” He spent 72 days in “residential surveillance at a designated location” (RSDL) – the Chinese regime’s term for detention in a “black jail” – incommunicado, with no access to legal counsel, entirely outside the justice system. He then spent a year and five months in a detention center and another five months in jail.

Both men were subjected to forced televised confessions. Both men endured forced prison labor, contributing to the production supply chains of major international brands. And both men emerged more determined than ever to warn the world about the threat the Chinese Communist Party regime poses to us all.

I had been involved with Lee Ming-che’s case since I first met his courageous wife, Lee Ching-Yu, in London in 2018. I stayed in touch with her, met her again in Taipei the following year, wrote articles about her imprisoned husband, and tried to lend my voice to her campaign for his freedom. So it was an emotional moment when I not only met him – now a free man – for the first time, but saw him reunited together with his wife. The three of us hugged.

I knew less about Lee Meng-chu’s case until shortly before we met, and was humbled to be meeting him just three days after his return home. He had been released from prison in July 2021, two years after his arrest, but was prevented from leaving China for over two more years due to an “exit ban,” as he had been “deprived of political rights” as part of his penalty. Upon arrival in Taipei, he kissed the ground of his homeland.

Astonishingly, once out of prison, he was free to roam around China even though he could not leave the country. He travelled to more than 100 cities, met Chinese dissidents, and then finally returned to Taiwan after spending five weeks in Japan.

What do the two Lees’ stories tell us?

Three things.

First, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime has absolutely no respect for truth, justice, human dignity, or the rule of law.

Second, the CCP does, however, care more than we realize about its image, and can be more responsive than we might think to international scrutiny and pressure.

And third, what happened to both men could happen to any of us, if the free world does not stand up to Beijing.

In captivity, both men were plunged into China’s vast world of prison labor, which feeds the supply chains of global manufacturing brands. Lee Ming-che was forced to work 14 hours a day, seven days a week, on a production line making gloves for export to the United States, in total contravention of China’s own prison laws. Lee Meng-chu had to assemble computer keyboards, transformers, and other electronic gadgets for over 10 hours a day. Both men were required to endure propaganda classes when they had time off.

Both men survived crowded 19 square meter cells, with one toilet to be shared by up to 20 men, but their cellmates were prohibited from speaking with them. According to Lee Meng-chu, one brave Chinese cellmate plucked up the courage to whisper to him: “I need democracy and freedom.” Lee Ming-che had a similar experience, claiming that prisoners sought him out to express appreciation for what he had done.

Lee Ming-che said he was never tortured physically but witnessed “many instances of pepper spray or electric shocks” against other inmates. Torture was “ubiquitous, common,” he added.

For him, instead of direct physical torture, the authorities chose psychological torture. “Their approach was to physically and psychologically wear you out – with bad food, bad smells, lack of sleep, and no hope,” he explained. “They tried to erase all hopes. The only hope we had was the aspiration for better food, the hope of survival.”

During his two months in a “black jail” he had no windows, no sunlight, no sense of time, and no one to speak to. “It was very torturing mentally,” he recalled.

“In fact, I wanted the police to interrogate me, just so that I would have someone to speak to. People would think physical torture is worse, but actually mental torture is worse. When you are tortured physically, you long to live. When you are tortured mentally, you long to die.”

They denied Lee Ming-che’s wife the right to visit many times, and delayed receipt of letters. She sent him books, most of which were confiscated. Unsurprisingly, those that were confiscated were books on Chinese history written by foreigners, books critical of the Soviet Union, and books on philosophy and “keeping the mind free,” as he put it. Strangely, George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” and “1984” slipped through. His wife sent between 400 and 500 books over four years, but he only received a tenth of them.

Yet Lee Ming-che believes his conditions improved as a result of his wife’s worldwide public advocacy campaign. “Public advocacy helps,” he told me emphatically. “It is very important.” Remarkably, he said, he never saw himself as a “prisoner,” but rather as a human rights advocate, even when in jail. “So it is very important for foreign governments to advocate for foreign prisoners jailed in China.”

Lee Ming-che is in no doubt that his ordeal was not simply against him, but “a threat to Taiwan and the world.” And he is equally in no doubt that Xi Jinping wants to invade Taiwan, which would pose “a direct threat to international law and world peace.” He points to what China has done in Hong Kong over the past four years, and believes it signifies its intent to “clamp down on democracy around the world.” China, under Xi, is an “expansionist threat” and “Taiwan is first in line as a target,” he warned.

Lee Meng-chu was arrested because he had postcards with the words “love,” “peace” and “compassion” on them. A regime that feels so threatened by these words is self-evidently a threat to world peace and freedom.

The international community should take time and care to learn from the two Taiwanese Lees’ stories. If we don’t stand up to Beijing now and defend freedom and the international rules-based order, and prevent an invasion of Taiwan, they could become our story too. “Peace through strength” – Ronald Reagan’s old axiom – is needed today more than ever.