The Diplomat author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners, and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Jeff Alstott – founding director of the Center for Technology and Security Policy (TASP) and a professor of policy analysis at Pardee RAND Graduate School – is the 395th in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.”

Identify guardrails in the global governance of AI.

“AI” is too large a space as to be a useful target of governance, covering everything from facial recognition to self-driving cars to large language models. I expect many applications of AI will simply be improved versions of software tools we already have, like note-taking applications and file storage systems. Addressing them all together is impractical.

However, there is growing international consensus that broadly-capable AIs like Open AI’s GPT-4, Anthropic’s Claude, and Google’s Gemini pose particular threats to nations’ security and public safety. These AIs already are showing some initial indications of capabilities that non-state actors could use to do mass harm, and experts expect that future AIs will soon become even more capable.

I’m particularly excited about efforts at RAND and several other organizations to assess if and where national security threats arise from broadly-capable AIs, distinguishing between when an AI can do something merely unfortunate vs. truly dangerous. An AI that points out to an angry 16-year-old that bioweapons are a potential tool is unfortunate but likely not dangerous; an AI that instructs them how to successfully resurrect smallpox is a massive problem. When real threats arise, government oversight will be needed to prevent mass harm, just as we do with other powerful technologies like rocket launches.

Examine China’s role in shaping the global governance of artificial intelligence.

Governing bodies around the world are developing systems to ensure that current and future broadly-capable AIs are handled responsibly. The U.S. recently released an executive order that introduced reporting requirements when AIs are developed at the capabilities frontier, including reporting safety and security test results and mitigations. The EU just passed its AI Act, which includes prohibitions on AIs that pose systemic risks. The U.K. convened world leaders and top labs at Bletchley Park during the 2023 AI Safety Summit to discuss these issues, and Parliament is now considering a bill to regulate AI.

China’s regulation of AI is still evolving, as current regulations are being implemented and iterated on; it seems likely they will move to also address the threats that the U.S., U.K., and EU have targeted.

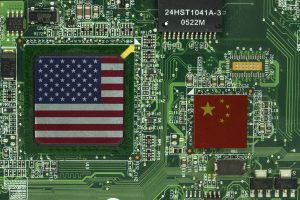

Compare and contrast the role of the U.S. and China in setting standards for AI governance.

The U.S. will continue to regulate AI systems much less than China does. This is appropriate, given that only a certain class of systems pose national security issues. China has taken a more interventionist approach to its AI industry, not just in issues of national security but across all sorts of AI applications, as it does in other parts of its tech industry.

This is most clearly seen in the U.S. and China’s contrasting approaches to AI’s political outputs: In the U.S., AIs are allowed to have different political postures. This even seems to be a frontier of competition: While OpenAI has sought a particular view of political neutrality with ChatGPT, Elon Musk’s xAI released Grok with the promise of a less censored AI. China, on the other hand, seeks to ensure all AI systems deployed there always toe the party line: All AIs in China need to avoid making unwanted political judgements or commenting on certain subjects that are politically sensitive.

U.S. companies are working to keeping their AIs from markedly increasing the prospect of real-world violence, but AIs can and do have different politics. Standards along the U.S.’s narrower sets of concerns are likely to be internationally viable. In contrast, China’s idiosyncratic political concerns are less likely to export well.

Analyze the inclusion of China at the Bletchley AI Summit in November.

With new AIs like Kimi and Yi-34B, and advancing indigenously-produced computing power, China has shown that its companies are capable of producing AIs at or near today’s capability frontier. The U.S. and China both will use their supply chains to influence each other and other countries, be that through export of their AIs or their computer chips used to create and run those AIs. While the U.S. and China will be competing, there is some room for cooperation, such as to avoid catastrophic risks from AI proliferation. As such, it was particularly helpful that China came to the table at the AI Safety Summit. I expect that many AI negotiations are to come, but it is a very important first step.

It is possible countries near the frontier of AI development and chip production might find themselves in a situation akin to that of the Nuclear Suppliers Group, built by the U.S. and USSR: Rival countries working together to control the export of potentially dangerous resources to only those countries which prove that they can be responsible with it. Both the U.S. and China would be essential members in any such regime.

Beyond the scope of the AI Safety Summit, I would also like to see international cooperation that ensures in an AI world that personal privacy is protected and that civil liberties are enhanced. However, China’s meaningful partnership there seems less likely, so we will need to isolate our concerns and make advances on each individual topic as we can.

Assess U.S. national security implications of China-U.S. AI competition.

Maintaining a lead in AI development, in technology as a whole, and in economic strength is absolutely essential to U.S. national security and competitiveness. In the last year and a half, the U.S. has taken several proactive steps to maintain and grow this lead: Export controls have slowed China’s ability to acquire state-of-the-art chips used to create broadly-capable AIs, while the CHIPS and Science Act has accelerated the U.S.’s domestic chip production and scientific research. For the U.S. to maintain its lead against the pacing competitor of China, such efforts will need to continue to grow in scale and sophistication.