After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, North Korea implemented a strategy of strict prevention that involved a full closure of the border. As a result, Pyongyang significantly reduced its diplomatic activities.

After Pyongyang decided to relax its epidemic control measures last year, Mongolia was one of the four countries allowed to rotate its diplomatic personnel in North Korea. The other three countries are China, Russia, and Cuba.

It’s well known that North Korea is looking to strengthen relations with Russia and China, especially amid the context of the Russia-Ukraine war. Less attention goes to the fact the the ambassadors of Mongolia, Cuba, and other countries in Pyongyang are also actively promoting bilateral relations. For example, Choe Ryong Hae, chair of the North Korean Supreme People’s Assembly’s Standing Committee, held talks with new Mongolian Ambassador to North Korea Erdenedavaa Luvsantseren after receiving his credentials in late January.

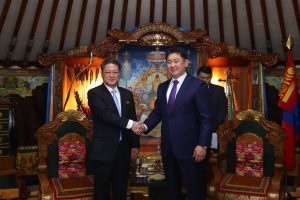

Now, for the first time in five years, North Korea has sent an official to visit Mongolia. On March 10 and 11, Foreign Deputy Foreign Minister Pak Myung Ho of North Korea was in Ulaanbaatar, meeting with not only his direct counterpart but also Foreign Minister Battsetseg Batmunkh. What’s more, Pak was feted with an elaborate banquet and received a highly anticipated meeting with Mongolia’s leader, President Khurelsukh Ukhnaa, who called him “an old friend.”

North Korea has been invited to send representatives to attend the Ulaanbaatar Dialogue scheduled to be held later this year, as well as the World Women’s Congress to be held in Ulaanbaatar. Last year, North Korean Foreign Minister Choe Son Hui was invited to participate in an international event with Mongolia, but she did not attend. Instead, North Korean Ambassador to Mongolia O Sung Ho delivered a speech on her behalf.

Pak’s visit to Ulaanbaatar should be considered significant news, indicating that Pyongyang is attempting to re-engage with the international community – and not just with Russia and China – through various means. North Korea has even reportedly been using Mongolian channels to make contact with Japan, a staunch U.S. ally, in recent months. With that in mind, it’s perhaps not a coincidence that a few days before Pak’s arrival, the political and military security dialogue between Mongolia and Japan was held in Ulaanbaatar.

Further adding to Mongolia’s relevance for the Korean Peninsula, South Korea is also actively promoting relations with Ulaanbaatar. South Korea’s Indo Pacific Strategy, published in 2022, specifically mentioned Mongolia as strategic partner “with whom we share values.”

Recently, South Korea announced plans to establish a Rare Metal Cooperation Center with Mongolia to produce key minerals used in semiconductors, part of global efforts to diversify supply chains.

On the soft power front, young Mongolian people influenced by the Korean Wave are more inclined to study and work in South Korea. Currently, there are around 5,000-8,000 Mongolian students studying abroad in South Korea. Meanwhile, there are now over 20 universities in Mongolia offering Korean language majors, which is quite a large number for a country with only 3.3 million people.

Seoul apparently took notice of Pak’s visit to Mongolia. While North Korea’s deputy foreign minister was holding talks Ulaanbaatar, South Korea announced it would provided $200,000 in emergency humanitarian assistance to Mongolia to help overcome the worst dzud – a snow disaster that decimates livestock in particular – in 30 years.

Recently, the political atmosphere on the Korean Peninsula has become increasingly tense. North Korea took radical measures earlier this month by announcing the abandonment of all economic cooperation agreements with South Korea. This decision marks North Korea’s intention to completely sever ties with South Korea, following its public abandonment of the goal of reunification and closure of government agencies that promote inter-Korean relations.

However, South Korea was not shaken by this move and instead adopted an unexpected strategy, establishing diplomatic relations with Cuba and bringing new dynamics to international relations. Seoul announced that on February 14, the South Korean Permanent Mission to the United Nations and the Cuban Permanent Mission to the U.N. reached an agreement in New York to establish bilateral diplomatic relations.

Since then, North Korean media have stopped reporting news about Cuba, indicating Pyongyang’s dissatisfaction. Prior to this, Cuba was one of the countries with the most media coverage in North Korea, second only to China and Russia.

North Korea’s response has been to actively seek contact with other countries beyond Russia and China. Pyongyang is hoping not to lose any more “old friends” to South Korea. In addition to strengthening relations with Mongolia through Pak’s visit, Pyongyang is also trying to improve relations with Japan. This strategic shift has two goals: to break the current diplomatic isolation and to attempt to undermine the unity of countries such as the United States, South Korea, and Japan.

However, this series of actions and countermeasures all demonstrate a profound truth: On the chessboard of international relations, friendship and hostile relations between countries can change at any time, while only national interests remain unchanged. Every diplomatic decision is carefully considered with the aim of maximizing the protection of national interests.

In this seemingly unsolvable diplomatic game, each country is striving for the most favorable position for itself, and the ultimate result may be a new situation that no participant can fully predict. Only time can reveal the answer to this complex and ever-changing challenge in international relations.