With the 2024 national elections in India underway, people of Indian origin — often termed non-resident Indians — living outside India are influencing, spreading the word, and commenting on Indian politics.

Nowhere are Indian diasporic politics more important than in the United States, home to the single largest Indian population outside of India.

There are nearly 5 million Americans of Indian descent, most of whom are first-generation and second-generation Indian immigrants. Many occupy positions of prominence, including sitting Vice President Kamala Harris, whose mother was from India, as well as the current CEOs of Google and Microsoft. There are also many prominent diasporic Indians in major American newspapers and think tanks, who may be able to give voice to issues for a global audience in a way that the domestic Indian media cannot.

Because most of these Indian Americans are recent immigrants, or the children of recent immigrants, many are still heavily invested in the goings-on of their ancestral land. Instant electronic communication and the wide availability of media, such as movies and music, make connecting with India in real-time easy.

Demographic heft is not the only reason why the Indian American diaspora is an important element of Indian politics; the United States is also the world’s premier power and wields enormous influence worldwide, including in India. Voices supporting or criticizing India from the U.S. are much more amplified and part of the political discourse in India than voices in other countries.

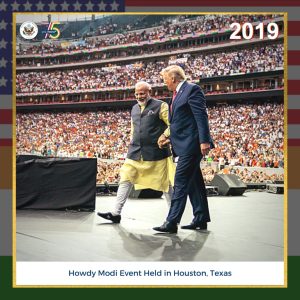

There is no question that there is a nexus between the Indian American diaspora — especially first-generation immigrants — and Indian politics. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) enjoys considerable support among the Indian diaspora in the United States; 48 percent of Indian Americans approve of Modi, while 31 percent disapprove of him. Modi is known for his huge rallies in the United States, including one in 2019 in Texas attended by then-President Donald Trump.

Both major Indian parties, the BJP and the Indian National Congress (INC), have branches in the United States, which impact “funding, campaigning and spreading India’s influence.” The BJP’s diasporic arm, the Overseas Friends of the BJP, is much larger and better organized than the INC’s equivalent, the Overseas Friends of Congress. The Overseas Friends of the BJP is particularly well-funded and large, and according to The Economist, it sent over 3,000 Indian American volunteers to India to put up posters and make calls. However, as important as fundraising efforts by diaspora groups in the U.S. are, they won’t make or break the BJP or any other party in the context of India’s electoral politics.

The diaspora in the U.S. is somewhat self-selecting. A disproportionate number of wealthy, college-educated, English-speaking, liberal, and irreligious Indians tend to migrate to the United States. The Indian American community is only 51 percent Hindu, well below the almost 80 percent of the population they form in India. While 10 percent of the Indian American community is Muslim, 18 percent is Christian, and 5 percent is Sikh, well more than the proportions of the population the latter groups form in India: 2.3 and 1.7 percent, respectively.

Many Indian Americans are from states in India that do not traditionally support the BJP. Thus, these are all groups that are less invested in the BJP than the average Hindu Indian in India.

The U.S. is also home to politically active Muslim and Sikh groups that oppose the Indian government in a way that would be difficult in India itself; some of the latter support Sikh separatism, giving the Indian government a major headache.

In any case, few of these diaspora groups can vote in Indian elections: only Indian citizens who vote in person can participate in the polls.

The nature of the involvement of Indian Americans in Indian politics will likely change with the next generation. Based on my own anecdotal experience as a second-generation Indian American, knowledge and interest in Indian affairs among my generation is generally minimal outside of some specific circles interested in journalism, development issues, or international politics.

Second-generation Indian Americans have a closer connection to food, popular culture (i.e. music and films), and sometimes religion, but it is not surprising that political issues that have no impact on the average Indian American are of little interest to them. But while there is less mass interest among second-generation Indians in Indian politics, specific groups of people, such as activists and politicians, can have a big impact on India-U.S. ties.

Regardless of generation, Indian Americans are more likely to be liberal when it comes to issues in the United States. According to a report by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “Indian Americans’ policy views are more liberal on issues affecting the United States and more conservative on issues affecting India.” This is because the political questions that occupy the minds of Indian Americans tend to be those more aligned with liberal politics in the U.S.: immigrant rights, church-state separation, and racial equality. This behavior is pragmatic, not ideological: Hindu Indian Americans are less concerned about majoritarianism in India than in the U.S., where they are a minority.

However, a substantial number of Indian Americans also voted for Trump, perhaps because of a convergence in nationalistic worldviews. But their children, who grow up as minorities in the United States without experiencing life in India, may often assimilate the political views relevant to their lives in the U.S., and are less likely to have much in common with many Trump supporters.

Modi himself has sought to maintain good relations with both Republicans and Democrats in the U.S., and Indo-American ties have deepened during both the Trump and Biden administrations.

Once in college, Indian American students who are inclined toward politics have a good chance of assimilating into the dominant ideologies on campus, supported by professors and peer groups. These tend to be progressive, so students who study or engage with India in an academic environment are likelier to approach sociopolitical issues there from the left than from the right or through a military or neoliberal economic lens. For example, the issues of Kashmir and Gaza or caste in India and race in the U.S. are frequently linked and seen as part of the same struggle against oppression. Attitudes toward India, especially toward the current BJP government, tend to be negative among the academia in the U.S. The group of Indians with the lowest approval rating for Modi are natural-born Indian Americans, citizens of the United States.

This line of thinking in the academic world may have some impact on Indian politics itself. For example, opposition politician Rahul Gandhi of the Congress Party has begun talking about the need for “equity” for castes in India, a term that only recently grew in popularity because of its adoption in the U.S.

Other than the relatively small groups of activists who are extremely passionate about domestic social and political issues in India, many Indian American politicians can push for closer ties between the U.S. and India, which is probably how the diaspora can be most helpful to India — by promoting stronger economic and military ties, and shielding India from criticism. Many Indian American lawmakers in the U.S. Congress, despite being members of the Democratic Party and liberal in the American political context, take a neutral or positive stance toward the current BJP government in India. For example, when Representative Ilhan Omar of Minnesota introduced a bill to criticize India’s stance on religious freedom in 2022, no Indian American members of Congress supported it. In 2023, Indian American Rohit Khanna, a Democratic representative from California, co-invited Modi to address the U.S. Congress, a decision that garnered support from both major U.S. political parties.

Most Indian American representatives subsequently declined to sign a letter circulated by some lawmakers alleging the erosion of human rights in India. Another Democratic representative, Shri Thanedar of Michigan, recently proposed a Congressional Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh and Jain American Caucus and declared his support for Israel. Mutual support for India and Israel and advocacy for stronger ties between the U.S., Israel, and India is a popular theme among Indian American politicians in the U.S., whatever else they may believe.

The United States still attracts millions of immigrants from India, so there will be many first-generation Indian Americans for decades, those with close ties to India and strong feelings for Indian politics. But the number of second- and even third- and fourth-generation Indians will continue to grow, as the children of immigrants settle down and assimilate into American society.

While this group is not as strongly involved with Indian politics as their ancestors, they can still be vital for advocating for strong people-to-people and nation-to-nation ties between the U.S. and India. The net effect of this will likely be continued strong relations between both countries, especially as Indian Americans help facilitate continued military and economic interaction between the two countries and soften any criticism.

Combined with the fundraising efforts of first-generation immigrants, the Indian diaspora in the U.S. is clearly a useful asset for the BJP and Narendra Modi, as his party is the main beneficiary of diasporic fundraising and policies that encourage investment and discourage any rights-based criticism. But the impact of these trends is unlikely to be election-altering.