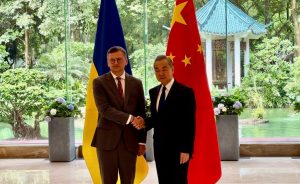

Ukraine’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Dmytro Kuleba was in China this week, attempting to persuade Beijing to use its leverage against Russia to end the war. On Wednesday, Kuleba met with China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, in Guangzhou; however, despite a stated desire to find a diplomatic solution, Wang expressed that “the conditions and timing are not yet ripe.”

China is perhaps best positioned to help broker a peace deal because of Xi Jinping’s close ties with Vladimir Putin and Russia’s dependence on Chinese trade, especially in oil, gas, and dual-use items – products with both commercial and military applications. Kuleba argued that it is in China’s strategic interests to help orchestrate a peace deal. Indeed, guiding negotiations would enhance China’s claims of being an inherently peaceful state and a great power alternative to the United States, aligning with China’s stated goal of being a leader in global security challenges.

This raises a question: If it is in China’s interest, and it has the leverage to do so, then why aren’t “the conditions and timing” right to mediate a deal between Ukraine and Russia?

The most obvious reason is that neither Ukraine nor Russia is ready to engage in peace talks. Putin’s conditions are that Kyiv cedes territory in Eastern Ukraine and pledges to not join NATO, which are both unacceptable demands for Ukraine. During his meeting with Wang on Wednesday, Kuleba once again stated that Ukraine is ready for peace talks once Russia is “ready to negotiate in good faith.” In other words, Kyiv will not negotiate until Russia gives up on its annexation ambitions. There is little room for diplomatic maneuvering in this situation.

However, if territory is the main point of contention, then why doesn’t China press Russia to give up on this goal? Isn’t it clear that Russia needs China more than the other way around, and therefore Beijing can risk upsetting Moscow? Well, China also has significant leverage against Ukraine, so a more likely explanation is that China finds Ukraine a more pliable actor than Russia at the moment. Or even more likely, China is taking advantage of export markets in Russia created by Western sanctions.

The less obvious explanations for Beiiing’s reluctance to use leverage against Russia lie in the non-tangible benefits China stands to gain from the conflict.

First, the visit by Kuleba to China is already generating good foreign propaganda to counter accusations made by the United States that Chinese entities are supporting Russia’s war. Beijing is already using Kuleba’s visit to “prove” that “so-called accusation of being a ‘decisive enabler’ in the Russia-Ukraine conflict made by the U.S. against China has not even been accepted by [Kyiv].” Of course this does not mean Kuleba should not meet with Beijing; it only shows how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) attempts to use such meetings to legitimize its position.

Second, China does not want to miss the opportunity to push its own peace deal, developed with Brazil, known as the “six-point consensus.” This explains why China did not participate in the Switzerland peace summit held last month – if Beijing can’t be in charge, then it loses the full benefits of mediating the conflict.

Finally, China must maintain good relations with Russia because of the former’s goal to offset U.S. power and influence, which depends partly on a strategy of authoritarian cooperation. Specifically, China aims to distance itself from the West in order to shield itself from internal and external ideological threats, which are seen as matters of national security. Strengthening relations with ideologically like-minded states satisfies this goal, which means China must preserve its credible commitment to its “no-limits” friendship with Russia – especially since there are few other equally strong authoritarian states to partner with.

These explanations resonate with the goals stated in the Communiqué of the Third Plenum of the CCP 20th Central Committee, including expanding foreign trade, being a leader in global governance, and fostering a favorable external public opinion environment. Because, of course, the priority that lurks beneath CCP interests is as always social stability and control.

In the end, even though it is in China’s interest to lead a peace deal in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the benefit of waiting for the strategically optimal time outweighs the potential risks.