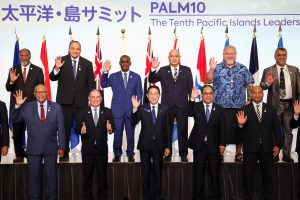

On July 18, the Japanese government hosted the 10th Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting (PALM 10). The objective of PALM is to facilitate dialogue and cooperation between Japan and the Pacific Islands region through the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF).

The PALM has been convened on a triennial basis since 1997. PALM 10 marked the first face-to-face meeting in six years and it was the first to be held in Tokyo in 27 years. For this meeting, Tokyo’s primary concern was to restore trust between Japan and the Pacific island countries, which had been eroded by the ALPS-treated water issue.

The PALM has traditionally stayed clear of the great power competition between the United States and China. In light of the prevailing regional dynamics, however, any deterioration in relations between Japan and Pacific island countries could tip the geopolitical scales. Consequently, restoring and bolstering ties assumed considerable importance.

In fact, PALM 10 exceeded expectations. The meeting provided an opportunity for both Japan and Pacific island countries to reinforce their partnership in addressing shared national, regional, and international challenges. In the preceding PALM Leaders’ Declarations, a clear distinction was evident between the positions of Japan and Pacific island countries. This was exemplified by the use of phrases such as “the Japanese Prime Minister committed to …” and “PIF leaders welcomed ….”

In the PALM 10 Leaders’ Declaration, however, the expression “Leaders” was frequently employed. The use of the wording “PALM partners” in the Joint Action Plan also underscored the egalitarian nature of the partnership, which has moved beyond the conventional relationship between donor and recipient countries to espouse a shared sense of ownership and responsibility. The background to this progress is characterized by a convergence of perspectives between Japan and Pacific island countries.

At PALM 8 (2018) and PALM 9 (2021), Japan’s vision of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) and the Pacific island countries’ vision, known as the Framework for Pacific Regionalism, were presented in a parallel format. At this year’s PALM 10, the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent (2050 Strategy) was the focal point, and Japan’s policies and its vision for Pacific island countries were presented in a way consistent with this.

It is notable that although the term “FOIP” is not explicitly referenced in the PALM 10 Leaders’ Declaration, the document does include several points that align with the vision of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific. This includes the maintenance of maritime order based on international law, the importance of conflict resolution through peaceful means without the threat or use of force, the strengthening of infrastructure development to enhance regional connectivity, the strengthening of cybersecurity capabilities, and the countering of the spread of disinformation. These elements are critical to the realization of the FOIP for Japan and also serve as the foundation for the 2050 Strategy for Pacific island countries.

Meanwhile, the joint action plan delineates specific forms of assistance to be provided by Japan’s Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Defense, and Japan Coast Guard. The plan encompasses initiatives designed to bolster the capacity of legal and judicial institutions, enhance public security, and strengthen control of narcotics. Moreover, the Japan Self-Defense Forces will engage in activities aimed at stepping up defense exchanges and strengthening disaster countermeasures through the use of satellite technology. Technical cooperation in the domain of maritime security is to be pursued. The Japan Coast Guard Mobile Cooperation Team will also provide assistance to enhance the maritime security capabilities of Pacific island countries, including combatting illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

Moreover, comprehensive efforts are being made to provide support for issues specific to Pacific island countries. These include mental health, regional cooperation and integration through enhanced financial sustainability and resilience, business matching, initiatives to address climate and disaster risks in the Pacific region under Japan’s Pacific Climate Resilience Initiative, and Japan’s support for the 2021 PIF Declaration on Preserving Maritime Zones in the Face of Climate Change-related Sea-Level Rise.

The leaders recognized the International Atomic Energy Agency as an authority on nuclear safety and concurred on the need for a science-based response with regard to the ALPS-treated water issue. Japan will continue to provide transparent explanations based on scientific evidence, and Pacific island countries are similarly working to enhance their scientific and monitoring capabilities in the region.

As for the relationship between Japan and Pacific island countries, the concluding paragraph of the PALM 10 Leaders’ Declaration explicitly states that “Leaders pledged that Japan and PIF Members will remain firm partners for each other in achieving together their shared vision in the Pacific region towards 2050, as it has always been.”

As a long-standing PIF Dialogue Partner, Japan demonstrated at PALM 10 a collaborative approach that aligns with the vision of Pacific island countries. The momentum that this has generated, with Pacific island countries assuming ownership and development partners collaborating on regional stability and prosperity, had a positive impact on the 53rd Pacific Islands Forum, held in Tonga from August 26-30, 2024.