China’s top two universities, Tsinghua and Peking, have edged closer to the global top ten; they are now ranked 12th and 13th respectively. Their ascent highlights China’s growing influence in global research and higher education. Both institutions have held the top positions in Asian university rankings for five years, underscoring China’s growing dominance in the region, with two-thirds of Asia’s top universities now based in Mainland China and Hong Kong.

China’s success is no longer confined to a few elite institutions. Whereas only Tsinghua and Peking appeared in the top 100 in 2018, today, four Chinese universities have made it into the top 50, seven are in the top 100, and 13 are in the top 200. Such progress is no accident; it reflects deliberate government investment and policy efforts to elevate the academic and research quality of Chinese institutions. Yet this increasing investment still lags behind rival countries like the U.K., U.S., Australia, and New Zealand, which spend over 5 percent of GDP on the sector. China spends 4 percent. Funding alone does not explain China’s success.

Beijing’s focus on education is longstanding, but progress has accelerated markedly under Xi Jinping. Deng Xiaoping, in his drive to modernize China, emphasized the importance of learning from other nations. Xi echoed this vision at the recent national science and technology conference, highlighting “sci-tech modernization” as key to China’s ambitions of becoming a global leader by 2035.

Reading Between the Rankings

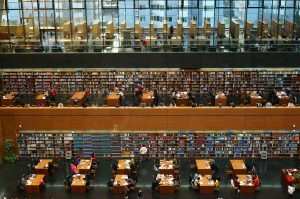

By the turn of the century, China began aligning its educational institutions with Western academic standards, using success metrics rooted in ranking systems established largely by the Western institutions. “Chinese institutions formed an obsession with ranking” and “globally recognized standards,” said a professor of social sciences at Peking University. The past 20 years have seen the Science Citation Index (SCI), established by American linguist Eugene Garfield, become a key metric for universities in China.

As Julian Fisher, the CEO of Venture Education – an education market intelligence company based in Beijing – pointed out, “university rankings are like tables of national GDP: they capture something, but also miss a lot of what really matters.” He suggested that the quality of a university should also be assessed through its “social life, preparedness for employment, societies, mental health support, engaging lecturers, the vibrancy and beauty of a campus, and opportunities for social impact.”

The overemphasis on producing reports and meeting stringent key performance indicators (KPIs) does not equate to a thriving academic life. The Peking professor suggested that Chinese professors live by the rule “publish or perish.” In 2015 when the U.S. tenure track system of six-year fixed academic positions was adopted in China’s leading institutions, everything changed. Rather than offering professional stability, the tenure track created an environment where academics are in a race to publish as much as possible in their first few years. The tenure track has been distorted in China, where an artificially high number of academic positions have been created in order to hire a surplus of youth academics who compete aggressively against one another, ultimately with no prospects of long-term employment. While this may meet the standards laid out by international ranking bodies, it does not promote the most creative or high-quality research.

China’s Soaring Research Output

In 2022, China surpassed the United States as the leading producer of highly cited scientific research papers. Since 2018, China has contributed 27.2 percent of the world’s top 1 percent most-cited papers, compared to the U.S.’s 24.9 percent. This achievement reflects not only the volume of Chinese research but also its quality and influence. Between 2009 and 2021, China’s scientific production increased five-fold and the number of citable papers rose significantly.

Beijing views collaboration and competition as complementary, not contradictory. Government statements have emphasized the need for both to achieve progress in science and technology, seeing cooperation and rivalry as two sides of the same goal: advancing innovation on the world stage. In this sense, Chinese institutions will continue to be international in their outlook and actively pursue partnerships with global institutions where there are natural synergies and possible research benefits.

However, Fisher pointed out that whilst Chinese universities are “extremely international,” international now means “Global South and not the Western world.” Historically, international partnerships between Chinese and Western universities, such as the University of Nottingham Ningbo China and Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, formed the foundation of China’s international outlook. This has evolved, with China now looking beyond Western partners, driven in part by the Belt and Road Initiative.

While being open to opportunities overseas, China will continue to pursue its academic nationalism. Some institutions, such as Renmin University, are already moving away from the global ranking systems, as well as preferring to publish in Mandarin instead of English.

China has also been making efforts to establish its own domestic standards and rule book. The Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index, established in 2000, is considered an “increasingly important standard for measuring academic output” for Chinese institutions, the Peking professor noted. In 2003, Shanghai Jiaotong University established its own ranking system, known as the “Academic Ranking of World Universities,” which is now viewed as the third most influential system alongside those produced by QS and Times Higher Education.

The next few years will likely see a dual strategy of collaboration and competition, as well as an increasing polarization between China’s outward and inward facing institutions. With the rise of more sensitive fields such as defense and aerospace, China’s domestic ecosystem of Mandarin publications will be viewed as a safer platform for distributing resources.

Chinese universities will also continue to leverage industrial partners. Peter Lu, partner in London and global head of McDermott Will & Emery’s China Practice, as well as a postgraduate supervisor at Peking University and a guest lecturer at Tsinghua University, believes that Chinese universities are “very entrepreneurial” and that growing collaboration with commercial sectors, such as the pharmaceutical industry, can fuel further success. He suggested that the amount of data available in China and the relatively less regulation surrounding its use give China a competitive advantage: “testing can be done quickly with a large sample size.”

The Path Ahead

Despite making strong progress, China’s higher education landscape remains varied in quality and scope. While the country’s top universities – the C9 League, often compared to the Ivy League – have made remarkable strides, the quality and strategies of other institutions vary significantly, with the overwhelming majority still lagging behind elite global standards. Perceptions of Chinese higher education vary worldwide, with many countries having more favorable views if they lack strong domestic higher education options. Much of this success stems from Beijing’s charm offensive in the Global South. Yet there are reasons to be skeptical about China’s continued success.

Economic challenges, shifting social attitudes and evolving domestic priorities may impact demand for higher education in the future. The growing phenomenon of “neijuan,” or “involution” – the sense of burnout and disillusionment among Chinese youth – may dampen domestic demand for degrees. Additionally, rival countries may reevaluate their own higher education policies if they perceive China’s rise as a threat to their global standing. But for now, the trajectory remains positive for China, helped by Western rivals, notably the U.K., Canada, and Australia, implementing policies that restrict the growth of international student enrollment, limiting the growth of their higher education sectors.

A hawkish Trump presidency – favoring tariffs and isolationism over cooperation – will pose significant challenges to China-U.S. academic collaboration. Whether Europe adopts a similar stance remains uncertain, yet all Western institutions would benefit from closely monitoring China’s progress. Striking a balance between competition and collaboration is crucial for addressing global challenges and fostering a more interconnected, resilient academic landscape. While national security concerns will justify some restrictions, overly siloed systems risk limiting visibility into each other’s advancements. To ensure both security and shared progress, nations must prioritize transparency and maintain avenues for constructive collaboration.