Europe’s interest in Central Asia has increased sharply following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. While this attention is mainly driven by Europe’s desire to diversify away from Russian fossil fuels, there are key differences in the ways in which individual European countries pursue their respective energy interests. Besides energy, geopolitical and security considerations increasingly play a role in Europe’s engagement with Central Asia.

France and Italy are particularly active in the region with their energy and defense industries. Their main focus is Kazakhstan, followed by Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

Energy

In the energy sector, France and Italy pursue similar but distinct interests. For France, uranium is key for the security of its energy system, which is dominated by nuclear energy. Between 2013 and 2023, France sourced most of its uranium from Kazakhstan (27 percent), Niger (20 percent), and Uzbekistan (19 percent). Following the 2023 military coup in Niger, reliance on Central Asian uranium is set to increase.

Paris’ focus on securing uranium supplies aligns with the ambitions of French mining giant Orano, which plays a significant role in the region’s uranium production. Orano holds a 51 percent stake in KATCO, the world’s largest uranium producer, in partnership with Kazakhstan’s national atomic energy company, Kazatomprom. Beyond Kazakhstan, Orano has expanded its operations into Uzbekistan, where it formed the joint venture Nurlikum Mining in 2019. During French President Emmanuel Macron’s November 2023 visit to Uzbekistan, discussions signaled a mutual desire to deepen this partnership, suggesting that France’s energy footprint in the region is set to grow.

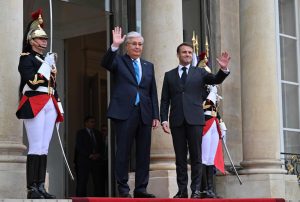

A visit by Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev to Paris in November 2024 aimed to cement the deepening partnership between Kazakhstan and France. Around 200 companies with French capital currently operate in Kazakhstan, spanning sectors such as transportation, aerospace, and energy. Among these, Orano remains pivotal, not only in uranium mining but also as a potential partner in an international consortium to construct a nuclear power plant in Kazakhstan, which is likely to also include Électricité de France (EDF). Furthermore, a roadmap for bilateral cooperation in critical raw materials, signed during the visit, highlights a shared focus on the exploration and mining of essential resources and the creation of sustainable supply chains.

While France’s energy strategy in Central Asia is centered on uranium, Italy has focused primarily on oil and gas. Central Asia, with Kazakhstan in particular, has become an attractive alternative fossil fuel supplier for Europe, although a large share of Central Asian oil and gas continues to be transported via Russia. Italy has accounted for 27.9 percent of Kazakh oil exports, much of which is redistributed across Europe. Italian energy giant ENI, partially state-owned, is deeply entrenched in Kazakhstan’s oil and gas sector. ENI holds significant stakes in two of Kazakhstan’s largest energy fields: a 16.81 percent share in the Kashagan offshore oil field and 29.25 percent in the Karachaganak gas-condensate field. Italy’s investments in Kazakhstan extend beyond oil; in January 2024, Italian companies, including ENI, pledged $1.5 billion in investments focused on energy and critical raw materials during a Kazakh-Italian roundtable in Rome.

Italy’s energy interests also stretch to Turkmenistan, home to the world’s fourth-largest natural gas reserves. While formal cooperation between Italy and Turkmenistan remains limited, recent developments could signal a shift. In August 2023, Turkmenistan signed a deal to supply natural gas to the European Union, potentially paving the way for Italy to become a future buyer. This highlights Italy’s growing role in diversifying Europe’s energy supply as it seeks alternatives to Russian energy, although mostly focusing on gas.

Together, these engagements reflect a broader European strategy of securing partnerships for energy resources in Central Asia. France and Italy’s efforts not only underline the region’s importance as a key supplier of uranium, oil, and gas but also signal the potential for future collaboration in renewable energy and critical raw materials essential for Europe’s energy transition.

Security

Since February 2022, Russia has been less keen to export arms, and this has created opportunities for France and Italy. France in particular has sought to capitalize on strained relations between Astana and Moscow to expand its defense industries. It has had a military cooperation agreement with Kazakhstan since 2011, which laid the foundation for arms trade, personnel training, and joint exercises. Over the past decade, French defense exports to Kazakhstan have included technologies such as Thales’ Ground Master 400 air defense system, first delivered in 2014 and now partially produced in Kazakhstan through a joint venture established in 2017. The supply of further Ground Master 400 systems was announced following Macron’s 2023 Astana visit, with the Élysée presenting the sale as “boosting the sovereignty” of Kazakhstan.

French defense ties with Kazakhstan extend beyond radar systems. Airbus, another key player, has delivered ten C295 transport aircraft since 2013, with additional orders. In April 2024, Airbus announced that it had completed the production of the first A400M military transport aircraft for the Kazakh Air Defense Forces, with a second A400M to be delivered on an undisclosed moment.

However, not all French ambitions have succeeded. Talks during Macron’s 2023 visit to Kazakhstan included the potential sale of Rafale fighter jets by Dassault Aviation, but in August 2024, Kazakhstan opted instead for six Russian-made Su-30SM fighter jets, claiming the Rafale jets were too expensive. France’s intended sale of Rafale fighter jets to Uzbekistan similarly did not materialize. This represents a notable setback for France’s aspirations on Central Asian defense markets.

Italy, meanwhile, has established itself as a significant supplier of military hardware in the region, particularly to Turkmenistan. Data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) shows consistent Italian defense exports to Turkmenistan, including AW139 and A-109K helicopters, Falco UAVs, and naval weaponry such as Compact 40L70 guns and Marte-2 anti-ship missiles. In 2021 alone, Italy delivered an array of advanced systems, including Super Rapid 76mm naval guns and C-27J Spartan transport aircraft. Italian companies have also sold to Kazakhstan, delivering similar equipment, such as M-346FA aircraft, naval guns, and Otomat-2 missiles. Smaller arms sales, including Beretta rifles and pistols to Turkmenistan, reflect Italy’s broader defense footprint.

Both France and Italy’s defense engagements in Central Asia align closely with the interests of their private defense sectors. Companies like Thales, Dassault, and Leonardo have found Central Asia to be a potentially lucrative market, supported by their respective governments’ efforts to boost their domestic champions and deepen strategic ties with key energy suppliers. This convergence of geopolitical ambition and private industry interest highlights the dual purpose of these defense deals: expanding influence in an increasingly strategic region while reinforcing energy security relationships.

Central Asia’s Perspective

For Central Asian governments, the increasing engagement of French and Italian energy and defense industries presents an opportunity to diversify their external partnerships beyond Russia and China while securing access to advanced technology and expertise. Kazakhstan exemplifies this strategy through its multi-vector foreign policy, which prioritizes engagement with a variety of international partners rather than alignment with a single bloc or actor.

The market in Central Asia is largely dominated by Chinese companies, which compete with the Europeans. Orano, for example, faces stiff competition in Uzbekistan from China’s state-run China Nuclear Uranium in the development of new mines. China is also the main customer of Turkmen gas, and while Turkmenistan undoubtedly views Europe as a lucrative potential market for natural gas exports, plans for a pipeline connecting it to Europe have so far failed to materialize.

Security concerns also factor heavily into the considerations of Central Asian governments. For Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, longstanding concerns about the spillover of Islamist extremism from Afghanistan have intensified with the resurgence of the Taliban. Besides facing real threats from militant groups, Central Asian governments have routinely used the label of violent extremism to jail political opponents. This gives security forces a critical role in the Central Asian political regimes.

While European defense partnerships can be attractive for boosting their security forces, Central Asian governments are likely to continue exploiting their position in a competitive marketplace to attain their required military hardware. Both European governments and companies face stiff competition in Central Asia. Russian influence in the region remains strong, which is exemplified by Kazakhstan’s choice of Russia’s Su-30SM fighter jets over the French Rafale.

Europe not only faces competition from Russia in the region; China, Turkiye, India and Iran, among others, have increasingly offered military training and equipment. This raises a critical question: To what extent can European countries and companies, often associated with high-priced equipment, establish themselves as viable long-term security partners in the region?

Central Asia’s evolving geopolitical role is not just about balancing external actors; it is about leveraging these partnerships to pursue their own national and elite interests. By engaging with a broader array of countries, Central Asian states aim to boost their sovereignty, diversify their economies, and strengthen their security forces. In this context, the growing presence of French and Italian companies in energy and defense offers potential benefits, but Central Asian governments will, for the time being, likely continue to hedge their bets among a range of global partners.