This month marks the 35th anniversary of Mongolia’s 1990 Revolution, which marked the beginning of the end of seven decades of communist rule in the land-locked Asian country. As a small state living in the shadow of Russia and China, the resilience and continued survival of Mongolian democracy is a testament that democracy can endure in hard places.

Since 1924, the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party (MPRP) had ruled the country with an iron fist. By 1990, Mongolia had few prerequisites for successful democratization. It was the poorest communist country in the world, with a per capita income of only around $2,000, only two-thirds as much as China and half the level of the poorest Eastern European country. Mongolia was a virtual Soviet satellite, dependent on the Soviet Union for 95 percent of its trade and on Soviet aid, and isolated from most forms of liberal Western linkage and leverage.

Mongolia’s 1990 Revolution in Retrospect

As frustration mounted over failed liberalization and the winds of change swept across the communist bloc, mass democracy protests broke out in Mongolia. On December 10, 1989, to commemorate international human rights day, a few hundred people gathered in Ulaanbaatar to announce the birth of a new non-communist opposition, the Mongolian Democratic Union (MDU). The group drew larger crowds for weekly demonstrations each Sunday through the spring of 1990. In mid-January, over 100,000 Mongolians filled Sukhbaatar Square. In mid-February, MDU activists announced new opposition parties.

On March 7, MDU activists launched a hunger strike, drawing inspiration from the Tiananmen Square demonstrations. MPRP elites were not able to overcome paralysis or mobilize Chinese-style repression. MPRP General Secretary Batmunkh Jamba was forced to resign by March 14; the MPRP replaced its entire leadership and under his successor Ochirbat Punsalmaa agreed to give up its monopoly on power and hold free elections.

In July 1990, the MPRP won 357 of 430 seats in the Great Hural (Mongolia’s parliament) following the first multiparty elections. The MPRP won 70 of 76 Great Hural seats in 1992. The democratic transition was complete by June 1993, when Ochirbat won the first direct competitive presidential elections as the liberal opposition candidate over the MPRP candidate.

Democracy and Development in Mongolia Since 1990

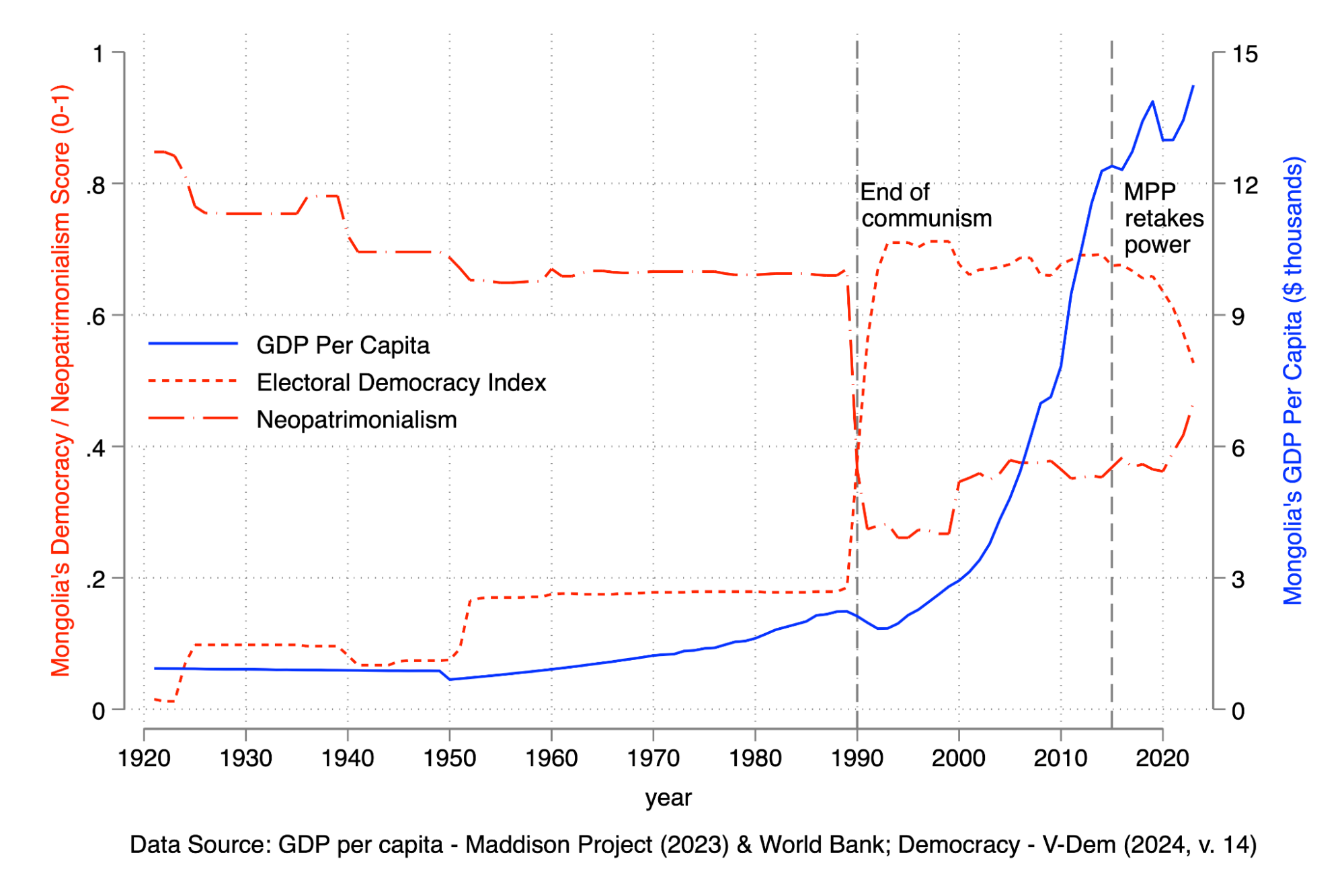

Mongolia quickly underwent a double transition. Economically, after an initial recession through 1993, long-stalled development took off as central planning was abandoned in favor of market reform. Per capita incomes septupled in three decades to $14,000 by 2023. The population of the capital tripled to 1.7 million since 1990, reflecting major urbanization, even though 40 percent of the population is still nomadic and a third still live in traditional yurts.

Politically, neopatrimonialism declined rapidly. Democracy became the “only game in town” by the late 1990s, even as challenges of corruption and accountability continued. There have been several peaceful transfers of power, with legislative control passing mainly between the Mongolian People’s Party (MPP) and the Democratic Party (DP). The MPP lost power in 1996 but participated in coalition governments from 2004 to 2012. Protests of the MPP’s electoral victory in 2008 prompted a state of emergency and led to several deaths.

The country has experienced some democratic backsliding since the MPP returned to power in 2016 after years in opposition, according to V-Dem. In 2023, though still an electoral democracy, Mongolia fell into the democratic “gray zone” in V-Dem’s Regimes of the World typology.

Figure 1: Democracy and Development Levels in Mongolia, 1920-2023.

Yet in the latest Freedom House scores for 2024, Mongolia still rates as “Free” with 84 out of 100 on political and civil liberties, equaling the score earned by the United States. Constitutional reforms in 2023 led to a larger unicameral legislature with a mixed electoral system, and increased gender quotas for women political candidates.

In the 2024 election, despite some international observers claiming the elections were free but not fully fair, the MPP victory was much slimmer than in 2016 or 2020. The MPP won just 68 of 126 seats. The DP gained 42 seats, a big improvement over 2020. Oyun-Erdene Luvsannamsrai was reelected as prime minister by a grand coalition of the MPP, the DP, and the HUN Party.

Resisting Sharp Power in Mongolia

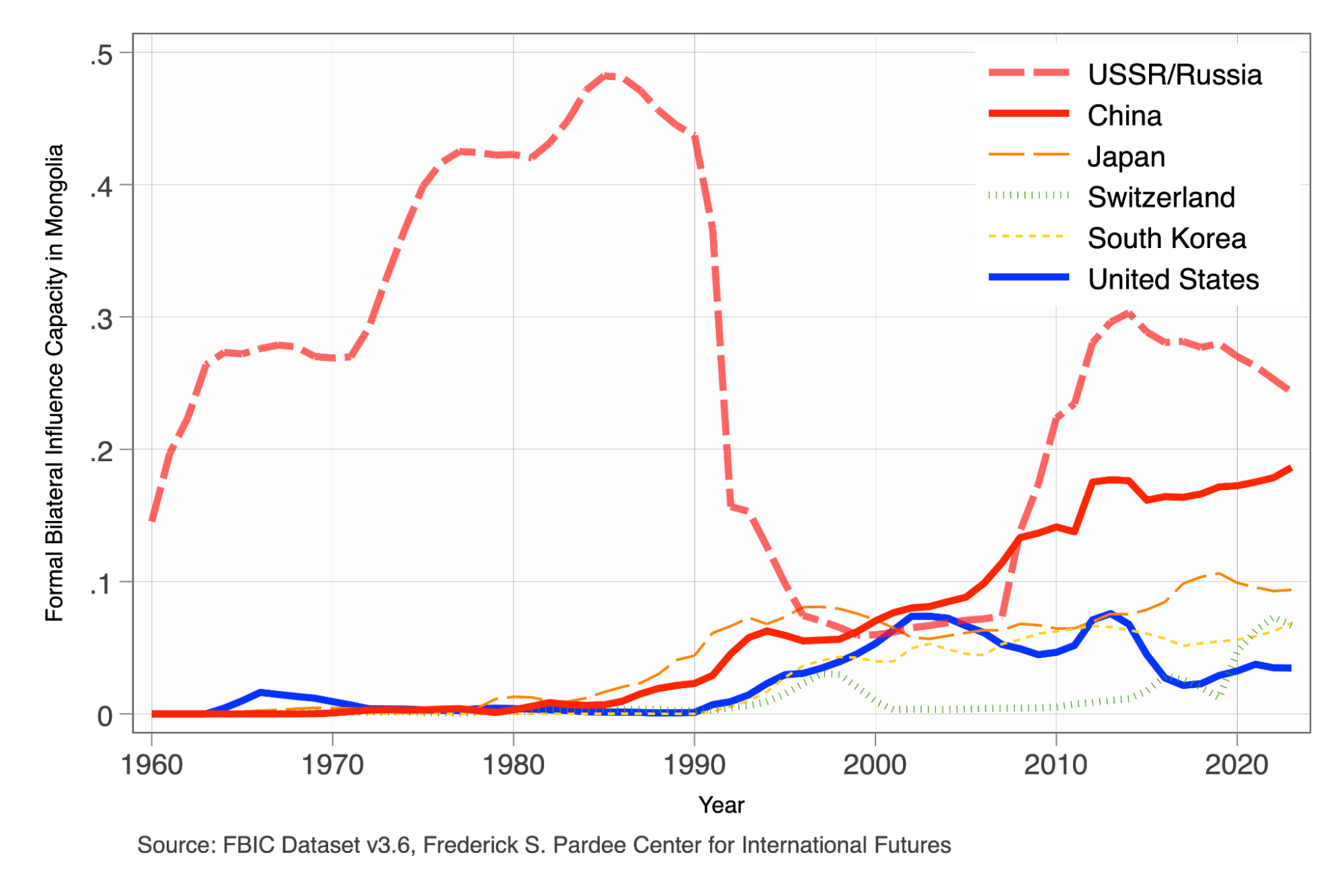

For most of the Cold War, Mongolia was essentially a Soviet client state, at least until the rise of Gorbachev and the “Sinatra doctrine” led Soviet military forces to withdraw between 1986 and 1992. The 1990 revolution and collapse of the Soviet Union led to the collapse of Soviet/Russian formal bilateral influence capacity in Mongolia, per FBIC data. From the late 1990s through the 2000s, no single state wielded disproportionate influence in Mongolia.

Figure 2: Formal Bilateral Influence Capacity Levels in Mongolia, 1960-2023.

In recent decades, Mongolia has been weaker than its larger neighbors, but has managed to maintain a measure of autonomy. In 2012, the last Lenin statue was quietly torn down in Ulaanbaatar. his year, Mongolia began using its traditional bichig script in government documents.

Mongolian foreign policy is premised on hedging through its “third neighbor” policy, triangulating cooperation with other major powers. For example, Mongolia signed strategic or comprehensive partnerships agreements with the United States in 2019, Canada in 2023, and Germany in 2024. The U.S. and Mongolia signed a critical minerals memorandum of understanding (MOU) in 2023.

Yet Russia and China have emerged as the two most influential outside powers in Mongolia, with China now Mongolia’s largest trading partner. Mongolia established comprehensive strategic partnerships with China in 2014 and Russia in 2019. In 2016, Mongolia joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Last September, Russian President Vladimir Putin visited Ulaanbaatar, using Mongolia to defy the International Criminal Court.

Although rising Chinese and Russian influence has led to concerns of the effects of corrosive sharp power elsewhere in East Asia (e.g. in Taiwan), so far Mongolian democracy has appeared not to be a major target of Russian or Chinese destabilization campaigns. As a geostrategically vulnerable buffer state wedged between Russia and China, Mongolia’s future may be a canary in the coalmine for the fate of “weak state democracy” in a world of restored great power competition. We should all wish it continued development and democratic success. But encouraging efforts to combat corruption may be more difficult as USAID is curtailed in the country, and Mongolia turns to other development partners.