Quantum computers are beginning to move from the fringe of what was only once theoretically possible to the center of a new technological frontier of geopolitical competition. Silicon Valley has unveiled groundbreaking progress in recent months, with Microsoft, Amazon Web Services and Google all announcing new quantum computing chips. Despite potentially accelerating years-long timelines of realizing an effective and scalable quantum computer, the harsh reality is that theorists and developers are still quite far from this hopeful target.

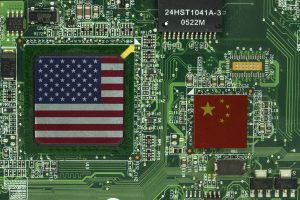

Meanwhile, the United States and China recognize the potential revolutionary reach these computers will introduce. Both countries have found themselves in another high-stakes technology competition that is rooted in a fear of being left behind and paranoia of each other’s intentions.

The CEO of Nvidia, Jensen Huang, sent publicly traded quantum companies through a rollercoaster ride in January when he said he believes quantum computers are likely still up to two decades away.

Jensen’s comments seemed counterintuitive in light of the still hot-off-the-press headlines made by big-tech giants. Inside the quantum “bubble,” optimism is contagious and new announcements are accompanied with renewed hype.

Looking more closely, however, the quantum chip developments made by these industry-leading enterprises have not yet demonstrated real-world applicability. There is not yet convincing evidence that these chips can actually be used in quantum computers.

Since its release in February, Microsoft’s Majorana 1 chip has been criticized by experts in the quantum field, who say that there is not sufficient proof, as of yet, that the chip can perform the quantum functions it is advertised to be capable of. Amazon’s Ocelot chip is, admittedly, still only a prototype and likely behind competing quantum chip efforts. And Google’s Willow chip, despite having completed a function that would take a classical computer 10 septillion years to crack, solved a calculation which has no real-world applications.

The only real consensus that exists right now is that the needle is moving closer to the target, but by exactly how much remains unknown.

These press releases further fuel the scientific competition that exists between the United States and China. Just as the Chinese firm DeepSeek shook the artificial intelligence landscape with their new AI model, big quantum announcements spook Chinese stakeholders in their efforts to keep pace with the United States. China, which is home to Jian-Wei Pan, the “father of quantum computing,” has also become the subject of U.S. targeted export controls on identified hardware components required to construct quantum computers. Like semiconductors, quantum computers are increasingly becoming a focal point of contention. From the United States’ standpoint, there are fears that without stringent export controls, Chinese quantum advances may equate to national security risks.

This technological race is creating an environment of suspicion and secrecy, and as a result there are increasing restrictions on opportunities to engage more cooperatively.

Returning from a recent trip to China, I experienced firsthand the effects of this tension. A colleague of mine in Beijing arranged a face-to-face meeting for me with a representative in the Chinese government. The meeting was arranged on a late Sunday evening in an unmarked residential building in northern Beijing. Instructed to travel via public taxi and to arrive alone, I could not help but wonder why this meeting was disguised with such an unusual amount of secrecy and discretion. Sitting in a windowless room, the government officials I spoke with used pseudonyms, insisted the meeting be off the record, and prohibited any electronics or writing utensils to even be in the same room. Why there was such an unusual amount of secrecy during our meeting that night, I believe, can only be explained with the risk psychology of the broader geopolitical tensions between the two superpowers.

While technological competition and arms races are not a new concept in global politics, there are many aspects of the China-U.S. race that are proving to be unique, not the least of which is the economic dependence they have on each other.

But quantum computers are a class of technology that is still only on the horizon; their role in today’s world is predominately theoretical. There is arguably a window of opportunity to create a framework of cooperative norms before the field develops into a conflict akin to a “Chip War,” referencing Chris Miller’s best-seller on semiconductors. These frameworks have been used before, most prominently with efforts to curb fentanyl and agreements to act on common threats, such as climate change.

Barriers to cooperation will exist in areas of quantum computing that involve national security and defense, like cryptography. But given the large range of beneficial applications that quantum computers are poised to offer society, cooperative frameworks should be negotiated and settled to advance research in areas of medicine, agriculture, climate, and more.

Failure to do so risks escalating the continuing trend of locking both countries into adversarial stances despite the longevity of the quantum computer timeline. This will likely stifle overall innovation potential and reduce responsible regulation for both the United States and China. By the same token intense competition can spur innovation, of course, but it should not be solely justified through popular public narrative that the United States and China are bound for larger scale conflict.