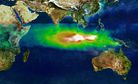

It’s on again. Malaysian, Singaporean and Indonesian companies with large plantation interests, along with thousands of small land holders, are burning off and razing forests in Sumatra, throwing enough smoke into the air to blanket Singapore to Southern Thailand and eastwards to Borneo.

Each year this phenomenon is well documented. The devastation of the environment and behind-doors loathing between countries unravels attempts to convince the world that the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) is a united political bloc worthy of respect.

Singapore has protested loudest. It would be refreshing to say that Indonesians responded with dignity and maturity. Instead they accused Singaporeans of being crybabies.

“Singapore should not be behaving like a child making all the noise,” said Agung Laksono, the Indonesian minister coordinating the response to the haze. “This is not what the Indonesian nation wants. It is because of nature.”

No, it is not – the haze has been an issue since 1997.

Laksono added, in regards to the acrid smoke billowing out of Sumatra, words to the effect that critics should stop whining and tough it out. I think I know what he is trying to say.

Indonesia would have the rest of the world believe it is incapable of controlling widespread arson within its own borders.

While Laksono continued to shirk responsibility on behalf of Indonesia and some major corporations, the pollution index in Singapore was reaching record highs and striking dangerous levels for children, the aged and infirmed. Schools in some parts of the region were closed and Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsieng Loong has warned that the haze could last until September or October.

Malaysia’s response was typical: bureaucratic and toothless. It wants to expedite the 15th Meeting of the Sub-Regional Ministerial Steering Committee (MSC) on Transboundary Haze Pollution that was scheduled to be held in August.

Natural Resources and Environment Minister Govindasamy Palanivel said this was in view of the worsening haze: “We do not want to wait until the end of August because we want to resolve the matter as soon as possible.”

Of course he expects the region’s hapless citizens to maintain a collective amnesia and simply forget that ASEAN adopted an agreement on cross-border haze pollution in 2002 to help co-ordinate efforts in fighting fires caused by slash and burn, and clearing for products like palm oil by large companies.

A separate regional action plan formulated last year to combat the haze — a peat land management strategy and a panel of experts to be assembled to assess and coordinate fire causing haze — has also been negotiated within the ASEAN framework. But success has been about as apparent as last year’s efforts to make rain through cloud seeding in order to douse the fires.

The treaty cannot be implemented because Indonesia has failed to ratify it. Nevertheless, at last year’s meeting ASEAN Ministers “expressed appreciation on the substantive efforts by Indonesia in implementing its Plan of Action in Dealing with Transboundary Haze Pollution.”

Indonesia’s refusal to deal with this issue can only further antagonize future regional relations.

Another complication is the nature of peat fires. They can burn for months and continue burning underground long after the surface blaze has been extinguished, usually by annual heavy rains. Southeast Asia has 24 million hectares of peat, 70 percent of which is in Indonesia.

Luke Hunt can be followed on Twitter at @lukeanthonyhunt.