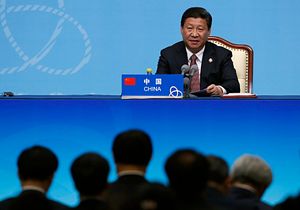

While the back and forth between the Chinese and U.S. and Japanese speakers at the Shangri-La Dialogue has gained considerable attention, less scrutiny has been paid to the comments by General Wang Guanzhong advocating a “new Asian security concept.” Wang was echoing Chinese President Xi Jinping, who similarly outlined a vision of an Asian security order managed by Asian countries at the fourth Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures (CICA) summit, on May 20-21 in Shanghai, China (Xinhua, May 21, 2014).

In many ways, advocacy of a revised security order to better accord with Chinese preferences is not new. PRC officials first introduced the principles of the new security concept in 1997. Around 2005, Chinese leaders unveiled a series of major concepts, including the Harmonious World, and its derivative, the Harmonious Asia, to provide a clearer vision of how China hoped to shape the global and regional order to accommodate the country’s rise. The new Asian security concept raised by Xi at the CICA summit, like the ideas promoted by preceding leaders, proposes the development of political and security relationships, institutions, and structures to complement the region’s deep integration with China’s economy. Details remain vague, however.

While the tenets of the Asian security order preferred by China are not new, PRC leaders have stepped up criticism of the U.S.-led security architecture in Asia as an obstacle to this vision. To be clear, Chinese leaders have not designated the United States an enemy. On the contrary, the urgency behind China’s advocacy of the “new type great power relationship,” a policy ideal of close cooperation between relative peer powers to co-manage contentious issues, belies the extent to which China, as a rising power, has hoped to avoid the onset of a classic security dilemma with United States, the status quo power. China, after all, continues to require regional stability to maintain its focus on national development. However, it is increasingly finding its security and developmental needs at odds with the current security order.

Security Concerns

The sources underpinning China’s growing opposition are deep and structural. They have little to do with the personal preferences of PRC leaders. Nor do they stem from reactions to statements by individual leaders or U.S. policies, such as the rebalance, although these may aggravate Chinese frustrations. Criticism of U.S. “hegemonism” and “Cold War mentality” has a long history, but for years it was aimed at specific policies, such as Taiwan arms sales. The latest criticism, by contrast, is more specifically aimed at the structural obstacles to China’s pursuit of regional security and the nation’s development. In the eyes of PRC leaders, those structural obstacles are defined in large part by the U.S.-led system of security alliances and partnerships in Asia. At the CICA summit, Xi criticized alliances as unhelpful for the region’s security. He stated that “It is disadvantageous to the common security of the region if military alliances with third parties are strengthened.” Commentary in official media has been even blunter. A typical Xinhua article observed that strengthening U.S. alliances can “achieve nothing other than buttress an unstable status quo” (May 21). The drivers underpinning this view consist of three types, expressed as concerns that: the current U.S.-led order enables U.S. containment of China; the nature of alliances emboldens countries to challenge China on sovereignty and security issues; and the alliance system led by the United States is incapable of providing lasting security for the region.

The fear of a U.S. ambition to contain China is deep and pervasive. China views U.S. promotion of liberal democratic values, human rights, and Western culture as driven in part by a desire to constrain PRC power. Moreover, Beijing is well aware of U.S. historical successes in activating its network of alliances to defeat aspirants for preeminence in Europe or Asia. The growing competition between China and the United States, manifest in friction points across policy topics from cyber to the South China Sea, and in the U.S. decision to adopt the rebalance itself, makes this threat all the more real and pressing. PRC leaders appear unconvinced by the incessant statements by senior officials in Washington that the United States has no intent or desire to pursue containment. But even if U.S. leaders could persuade Beijing of this fact, the mere existence of the security architecture allows the possibility of pursuing containment in the event bilateral relations sour.

China also objects to the alliance system as a threat to its security and sovereignty. This is especially true of U.S. alliances with countries that have antagonistic relations with China. Beijing finds the U.S. alliance with Japan more problematic than it does the U.S. alliance with countries like Thailand, with which China enjoys far more stable relations. In China’s eyes, an alliance with the United States emboldens countries to provoke Beijing on sovereignty disputes, threatening instability and potentially conflict. Antagonism with neighboring powers like Japan and the Philippines also threatens to escalate into a war that could draw in the United States, a disastrous possibility Beijing dreads. Reflecting these frustrations, a typical Xinhua commentary article bitterly noted that “the United States has not taken any concrete measures to check its defiant allies from confronting China.” U.S. efforts to reassure its allies through the rebalance and through criticism of China for “provoking instability” merely intensify these anxieties.

Chinese critics also question the effectiveness of the U.S.-led security architecture to address traditional and non-traditional threats. PRC media routinely criticize as destabilizing U.S. efforts to deter North Korea through military exercises and presence, advocating instead a reliance on dialogue through the Six Party Talks. Articles also question the ability of the U.S. and its allies to manage non-traditional threats. Regarding transnational crime, terrorism, and other threats, a recent Xinhua article claimed that the United States had “failed to win confidence that its power could, or at least is willing to, protect the interests of Asians from disaster.” Critics contend that the U.S. system of alliances and partnerships is too limited in capacity and narrow in focus to adequately address the range and complexity of security issues in Asia.

All of these grievances lead to a larger point. In Beijing’s eyes, the U.S. led security architecture is outliving the usefulness it once provided by ensuring the regional stability necessary for China’s development. Instead, China views the alliance system as increasingly incapable of providing lasting security and itself a potential source of threat. In the words of one Xinhua commentary, the “rhetoric of a peaceful Asia will be empty as long as the Cold War security structure remains.”

Structural Impediment?

What makes opposition to the U.S. system of alliances and partnerships particularly intractable is that such concerns are also driven in large part by China’s efforts to maintain domestic economic growth. The view that security is necessary for the country’s development, and that the domestic and international aspects of security are inseparable, is critical to understanding the source of Chinese criticism of the U.S. alliance system. At a meeting of the recently formed National Security Commission (NSC), Xi stated, “Security is the condition of development. We stress our own but also common security (with other countries).” Through the NSC and other newly formed small leading groups, Xi seeks to enact systemic and structural changes that can facilitate the country’s comprehensive development and improve security both internally and externally (Xinhua, April 15). To date, most observers have interpreted the pursuit of structural and systemic change in terms of domestic policy. The CICA speech confirms that the same directives carry profound implications for China’s foreign policy as well.

Chinese leaders have repeatedly premised the nation’s development on security provided by a more stable domestic and international order. As an export-oriented nation, China’s economic growth depends in large part on the performance of the global economy. With its share of world GDP expected to increase in coming years, Asia is poised to drive the global economy, which in turn is expected to increase China’s growth and prosperity. Much of the future growth in the global economy is expected to occur within the region. By some estimates, one third of Asia’s trade may be intra-regional by 2020. This makes peace and stability in Asia all the more critical to the region’s economic potential. As one commentary explained, “instability interferes with and retards Asia’s regional economic and trade integration process and economic growth momentum” (People’s Daily, May 11). And ensuring Asia’s economic potential is increasingly imperative to ensuring widespread prosperity for China’s citizens.

Because China’s domestic prosperity will is increasingly inseparable from the region’s prosperity, China has a strong incentive to seek greater control over the terms of the region’s security. For China to entrust the future that security to an outside power such as the United States and its allies is tantamount to expecting China to entrust much of its own prosperity and security to the United States and its allies.

Reshaping the Regional Order

Central authorities have opted instead to pursue a strategy of development as the principal means to achieve the domestic and international security needed to sustain the country’s growth. At the CICA summit, Xi Jinping stated, “Development is the foundation for security.” Indeed, it is worth recalling that as early as 1997, the 15th Party Congress report stated that “development” is the “key to resolving all of China’s problems.” The concept of development is so important to China’s approach to addressing security threats that it merits closer analysis. As used by China’s leaders, “development” means the calculated application of superior resources to change the economic, political, and security facts of a situation in order to extract goods of security, stability, economic gain, and national prestige. In the language of the CCP, this is a process which brings about the “progressive social qualitative and quantitative change in productivity from a situation” and thereby “brings benefit to the Chinese people.” While primarily economic, development also includes policies and actions which realize political, social, administrative, and other forms of “progressive” change.

China’s sovereignty disputes with its neighbors, including those with Vietnam regarding oil rig Haiyang Shiyou 981, with Japan regarding the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, and with the Philippines in the South China Sea, serve merely as a symptom of a broader problem in the eyes of Chinese leaders: the supersession of the regional political and security order by a new economic reality. China regards many features of the regional order as legacies of an era in which the U.S. enjoyed overwhelming economic, political and military predominance in the region, conditions which have eroded over time, and in the case of economics, no longer obtain. For China, the most lasting resolution therefore does not lie in “fixing” particular dispute issues, but in comprehensively “developing” the political, security, and social order to accord with a new reality defined by Chinese economic power. In a broad sense, regional integration serves a function similar to the pattern observed in domestic issues of unrest in which China seeks to address the source of instability through comprehensive approach to development. In both cases, China’s superior resources give it considerable leverage to both incentivize and pressure recalcitrant opposition into accommodation. In the words of a Chinese commentary, “Development is the strategy for treating insecurity; it eliminates the root factors which cause instability” (People’s Daily, May 20).

Development as a strategy for regional security also offers a way to deal with the current leader in a manner that minimizes the risk of war. China hopes to incrementally replace elements of the old with a new security order that is more strongly rooted in the source of Asia’s economic power. By demonstrating superior vitality and effectiveness, Beijing hopes that it will over time render a U.S. role superfluous. China’s approach to developing the regional security order thus reflects elements of both accommodation and revision, characterized by efforts to: shape cooperation with the United States; leverage economic power to reorient regional relationships; selectively accommodate elements of the current order; build and strengthen institutions and mechanisms which favor Chinese interests; and develop military power and counter intervention capabilities.

Shape cooperation with the United States. China seeks to build stable relations premised on a greater U.S. accommodation of PRC interests. Military cooperation with the United States demonstrates China’s status as a leading power in Asia and reassures the region that Beijing does not seek conflict with the world’s superpower. China also leverages bilateral cooperation to persuade the United States to restrain its allies.

Leverage economic power to reorient relationships. As the center of Asia’s economy, Beijing has considerable clout with which it can deepen regional interdependence and refocus bilateral relationships to emphasize trade and economic gains. This incentivizes countries to support China’s efforts to build enhance regional cooperation featuring a greater Chinese leadership role. Such relationships also raise the risk and cost for countries to challenge China over policy disputes.

Selective accommodation. China continues to participate in many institutions and organizations which feature U.S. leadership. So long as these groups do not pose a direct threat to Chinese interests, Beijing has little incentive to advocate their abolition. On the contrary, it is to China’s benefit to participate in, and shape, the agenda and activities of such organizations. At the regional level this includes the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the East Asia Summit, Shangri La Dialogue and others.

Strengthen alternative institutions and mechanisms. At the same time, however, China is reinvigorating or establishing alternative regional security and economic institutions and mechanisms which it hopes can demonstrate China’s ability to provide economic benefits, provide leadership, and promote a more lasting form of regional stability. The Six Party Talks, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the CICA exemplify this approach. China views these dialogues as complementary to the evolving network of economic institutions dominated by China, including the Bangladesh-India-Myanmar-China economic corridor, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the Silk Road Economic Belt, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, China-ASEAN Free Trade Area, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

Build military power and counter intervention capabilities. China’s military buildup supports its efforts to enhance its security by raising its defense capabilities. This raises the cost and risk of conflict for countries that oppose Chinese power as well as provides a useful hedge against the United States. The development of military counter intervention capabilities, in particular, provides the added political benefit of eroding regional confidence in the United States as a source of counter-leverage to Chinese power.

Chinese leaders view a consolidation of economic, diplomatic, cultural, and security influence as the most lasting way to realize the economic potential of Asia and elevate the standard of living for its people. The imperative to consolidate this influence provided the main impetus for the recent Central Work Forum on Diplomacy to the Periphery. For similar reasons, Chines officials have designated the periphery a “priority direction” for the nation’s diplomacy (People’s Daily, September 10).

The Risks of Strategic Divergence

Chinese leaders seek structural reform to both the domestic and international order to maintain economic growth and realize the country’s revitalization. Directives in high-level strategy documents such as the 18th Party Congress report and Third Plenum decision, and the establishment of central leading groups focused on systemic reform, underscore the urgency with which PRC leaders regard this issue. Because these reforms are viewed as necessary to enable the country’s continued development and survival, Beijing is unlikely to abandon these demands. On the contrary, the imperative to sustain growth will likely intensify pressure to realize these changes over time. The harsh criticism of the U.S. led security architecture seen in Xi’s remarks at the CICA summit and PRC commentary may thus well serve as a foretaste if China remains frustrated in its efforts to realign the regional order in accordance with its strategic priorities.

The United States is thus likely to find its system of alliances and partnerships in Asia an increasing source of contention with China. Senior U.S. policy makers have made clear that the United States has legitimate and important strategic interests in Asia. Moreover, the United States retains considerable strength as the dominant power in the region, even if some of its relative advantages have declined in recent years. The U.S. has reiterated the strategic value of its alliances and the importance of the interests of its allies. This leaves China, the United States, and its allies with increasingly complex and difficult decisions. Reassuring Beijing requires the U.S. to either weaken or redefine its alliance system to accommodate China’s security preferences. This could prove dangerously destabilizing as vulnerable countries realize they must take action to defend their interests. It would also mean a significant weakening of influence in a region of the world that is of vital strategic importance to the future of the U.S. economy. However, reassuring allies requires a greater U.S. willingness to confront China in sovereignty disputes and other issues. This risks deterioration in U.S.-China relations and potential destabilization of the regional order. China and the United States and its allies will need creative policymaking to balance these competing concerns and ensuring lasting peace and stability in the region.

Timothy R. Heath is a senior China analyst for the USPACOM China Strategic Focus Group. The views expressed in this article are those of the author’s alone. They do not in any way represent the views of U.S.PACOM, DOD, or the U.S. government.