Over at ChinaFile, Richard Bernstein and Ely Ratner discuss the possibility of the U.S. and China cooperating to fight terrorism. Bernstein argues that while such cooperation is desirable, in reality the prospects are hindered by Beijing’s tendency to label peaceful dissenters as “terrorists.” Bernstein welcomes China’s efforts to aid in the fight against Islamic State (IS), but also worries that China will take advantage of the situation to justify “repression of peaceful and lawful dissent in Xinjiang.” Bernstein concludes that, should China step up its role in global counterterrorism, the world “will not be so much gaining Chinese help in the real anti-terrorism fight as it will be collaborating in China’s ongoing violations of the rights of its Uighur citizens.”

In a similar vein, Ratner points out that Washington is reluctant to increase anti-terror cooperation with Beijing precisely out of fear that doing so “would help China develop additional capabilities to oppress its own people.” Ratner is correct; U.S. government officials often discuss counterrorism and human rights simultaneously, an indication of their concern over China’s approach. This attitude was fully on display at the Strategic and Economic Dialogue this year, where the discussion on counterterrorism included Secretary of State John Kerry emphasizing “the differentiation between terrorism and political activism – or political dissent.”

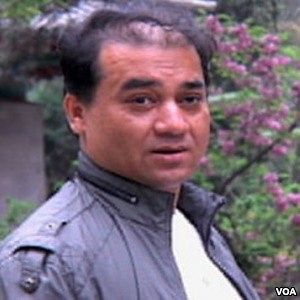

The fate of Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti is an example of China’s conflation of dissent and terrorism. Tohti was sentenced to life in prison on charges of separatism earlier this week. A Xinhua commentary blasted Tohti as “a separatist who incited ethnic hatred.” The piece also denounced Western countries for protesting Tohti’s sentencing. “For them, anyone, even those like Ilham Tohti who turn to extremism, could be named a freedom fighter as long as he is against the Chinese government,” Xinhua complained. The piece then explicitly drew a parallel between U.S.-led airstrikes against IS and the sentencing of Tohti: “China’s painstaking efforts to eradicate the three evil forces of terrorism, separatism and religious extremism in Xinjiang should have been viewed as part of the world’s anti-terrorism endeavors. Ilham Tohti should have been denounced as a criminal threatening the peace and stability of a country.”

Despite this diatribe, the Chinese government’s charges against Tohti have little to do with actual terrorism. Based on Xinhua’s report, Tohti’s primary crime was not actively organizing or planning terrorist attacks but running a website that criticized Chinese government policies. Tohti’s lawyer, Li Fangping, denied even these charges. “He hoped to unite Uyghur interests and national interests. None of his speech was in support of separatism,” Li Fangping told Reuters. Human rights organizations agree. “Tohti has consistently, courageously and unambiguously advocated peacefully for greater understanding and dialogue between various communities, and with the state,” Sophie Richardson, the Chinese director at Human Rights Watch told South China Morning Post. “If this is Beijing’s definition of ‘separatist’ activities, it’s hard to see tensions in Xinjiang … decreasing.”

Even if we accept at face value the charge that articles on Tohti’s website “incited ethnic hatred,” there’s a far cry between publishing articles and the violent actions undertaken by IS and other terrorists. Yet the Xinhua article ended with a laundry list of terrorist attacks within China in the past year, drawing a direct line between Tohti and violent terrorist activity. Other state media articles, including the Xinhua commentary quoted earlier, draw even more explicit parallels between Tohti’s actions and violent extremist groups such as IS.

It’s precisely this conflation of dissent and violence under the catch-all label of extremism, separatism and terrorism that leads to headlines like this one from the Washington Post: “China’s war on terror becomes all-out attack on Islam in Xinjiang.” The article points to evidence that Beijing is lumping conservative Islamic practices (such as women wearing veils) together with extremism and terrorism. Chinese intellectual Wang Lixiong summed up his view for the New York Review of Books: “They [Chinese authorities] don’t want moderate Uighurs… they wanted to get rid of him [Tohti] and then you can say to the West that there are no moderates and we’re fighting terrorists.”

The upshot, in a foreign policy sense, is that Western countries (and particularly the U.S.) are reluctant to cooperate with China on anti-terrorism because China’s definition of terrorism is shockingly broad. It encompasses not only Islamic State, but Ilham Tohti; not only the knife-wielding assailants at a Kunming railway station but Muslims seeking to hold private religious study sessions.In responding to Tohti’s sentencing, Secretary Kerry emphasized that “peaceful dissent is not a crime.” Kerry concluded, “Differentiating between peaceful dissent and violent extremism is vital to any effective efforts to counter terrorism.”

I’ve written before that U.S. concern over the way China defines terrorism is one of the major factors holding back bilateral cooperation on anti-terrorism. Even as U.S. officials seek greater Chinese cooperation in the campaign against IS, the sentencing of Ilham Tohti reminds us that such anti-terror cooperation will remain limited.