Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon has taken a stance on the issue of gay rights in South Korea. In an interview with the San Francisco Examiner, Park stated, “I personally agree with the rights of homosexuals.” He emphasized that, due to strong resistance from Protestant churches, only civil society has the power to “expand the universal concept of human rights to include homosexuals,” adding, “Once they persuade the people, the politicians will follow. It’s in process now.”

A 2013 Pew Research survey, quoted in a Korea Times article about Park’s interview, suggests that it is, indeed, “in process.” The survey found that only 59 percent of Koreans think homosexuality is unacceptable for society, down from 77 percent in 2007. The trend suggested by these findings should give hope to South Korean progressives. But what does a longer view indicate? Survey data from the World Values Survey are helpful here.

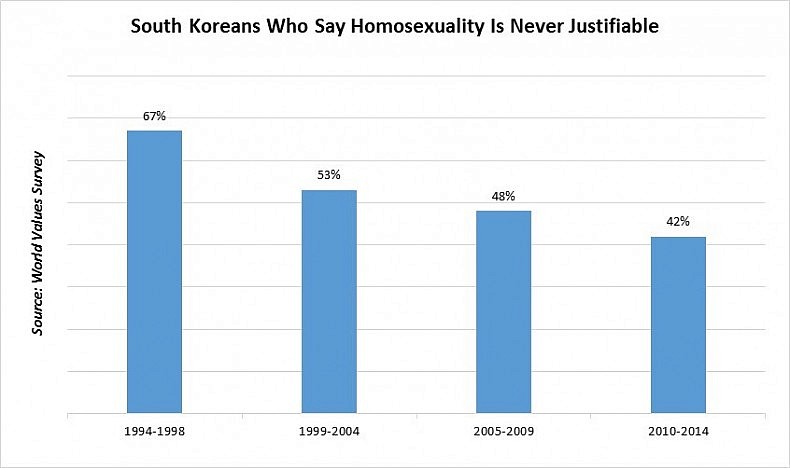

The World Values Survey (WVS) is a global research network that uses survey interviews to tracks changes and variations in basic values of people the world over. According to the website, “The WVS consists of nationally representative surveys conducted in almost 100 countries which contain almost 90 percent of the world’s population, using a common questionnaire.” South Korea is included. There are survey data for the entire duration of Korea’s post-authoritarian period, including a question on homosexuality. On a scale of 1-10, respondents are asked whether they find homosexuality “justifiable.” 1 means “never justifiable” while 10 means “always justifiable.” The results for those answering never justifiable during surveys conducted between 1994 and 2014 are shown below:

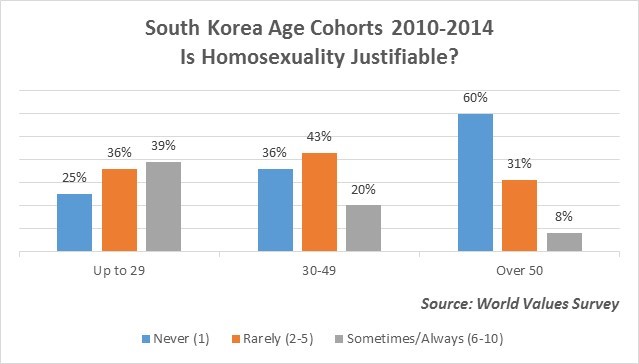

As the graph shows, people are increasingly finding homosexuality relatively more justifiable. It is a stretch to say that South Korean society finds homosexuality acceptable, but the trend is quite clear. This is even more the case among younger South Koreans. A snapshot of the breakdown of the question by age cohort for the latest survey wave highlights the stark generational divide (the coding is mine).

As the graph indicates, a majority of South Koreans over the age of 50 still view homosexuality as never justifiable. However, a plurality of South Koreans between the ages of 30 and 49 view it as rarely justifiable (2-5 on the survey); and a plurality of the youngest cohort said it is sometimes or always justifiable (6-10 on the survey). Furthermore, only a quarter of the youngest cohort says homosexuality is never justifiable compared to 42 percent of the population as a whole. This suggests that South Korean youth are relatively more accepting of homosexuals than are the older generations.

These findings are not surprising. As I’ve explored elsewhere, Ronald Inglehart’s “post-materialist theory” would predict that the younger generations in Korea hold what many would consider “progressive” political values. Some of these values are: tolerance for foreigners, gays and lesbians, support for gender equality, and a high priority given to environmental protection. The catalyst for this change is improving socioeconomic conditions, which raises standards of living and increases people’s sense of security. There is, in other words, a causal relationship between development and “progress,” though it is by no means a linear or deterministic relationship.

Thus, the “process” alluded to by Mayor Park is certainly underway. South Korean progressives should be bullish about the direction society is heading.