Zimbabwean politics is at a critical moment. Its 92-year-old president, Robert Mugabe, having led the country for more than 30 years, is vowing to run for re-election in 2018. However, his political party, Zanu-PF, is fracturing. His vice president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, has garnered many followers in the party and is expected to challenge Mugabe in the presidential election. His wife, Grace Mugabe, has also received factional backing within Zanu-PF and is interested in competing for the presidency.

The factional fights within Zanu-PF have been made public as both sides pointed fingers to each other in front of the press and now on social media. Even Mugabe found himself powerless to dismiss their jostling. His repeated calls to end factionalism have been unheeded. But he may also have benefited from pitting one faction against another while he retains firm control of power.

Meanwhile, the Zimbabwean economy is in a bad shape. Its currency was so worthless that it was ditched in 2009 to be replaced by the U.S. dollar and South African rand, among others. With 90 percent of the population without formal employment, the ruling party has seen social unrest on the rise and therefore has to rely more on political violence to crack down on protesters.

Due to its poor human rights record, Zimbabwe has few friends in the world. China is one of the few. In fact, it claims to be Zimbabwe’s “all-weather” friend, offering generous grants and investing heavily to boost the Mugabe leadership. But with Zimbabwe’s political future uncertain, China is walking a fine line as to taking sides with political factions and keeping China-sponsored assets safe from the threat of political turmoil.

China’s Economic Stake in Zimbabwe

Despite Zimbabwe’s uncertainties, China did not hesitate to grow economic and political connections with the country. In fact, while Zimbabwe was under EU and U.S. sanctions for its refusal to allow European observers in the 2002 election and for its brutal handling of protesters, China invested in at least 128 projects in the country from 2000 to 2012. Zimbabwe is among the top three Chinese investment destinations in Africa, attracting a total FDI of more than $600 million in 2013. Moreover, China was Zimbabwe’s largest trading partner in 2015, buying 27.8 percent of the country’s exports. Chinese companies have also been actively engaged in contractor services in telecommunication, construction, irrigation, and power.

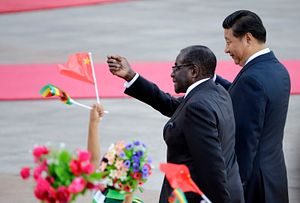

China’s brotherly relationship with Zimbabwe dates back to the liberation war era. The Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), the predecessor of Zanu-PF, received China’s financial and military sponsorship in its fighting with the rival faction supported by the Soviet Union. After independence, China continued to offer support to the Zimbabwean government, building a national stadium, hospitals, and power stations, and providing 35 percent of Zimbabwe’s imported arms from 1980-1999. In 2012, China donated $150 million worth of grain to help several Zimbabwean communities that were suffering from a famine. More recently, China pledged $46 million to build a new parliament for Zimbabwe as a gift. During his visit to Zimbabwe in December 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping called China Zimbabwe’s “all-weather” friend, and committed multi-billion-dollar energy and infrastructure projects, including a $1 billion loan to finance the expansion of Zimbabwe’s largest thermal power plant.

To be sure, China has been a benefactor of its political and economic ties with Zimbabwe. China’s yuan or renminbi (RMB) is adopted as a legal currency in Zimbabwe, which may help pave the way for the RMB’s internationalization, or if not, at least Africanization, as China’s currency has been given more weight in several African nations’ currency reserves.

With little serious competition from other foreign investors except South Africa, and with the support of Mugabe-led Zanu-PF, China has been able to take advantage of the Zimbabwean agricultural industry, which has huge potential but awaits capital injection. For example, Tianze, a local Chinese tobacco company established by the China Tobacco Import & Export Corporation in 2005, has given $100 million worth of interest-free loans to Zimbabwean farmers for tobacco production. Recently, more Chinese companies have invested in big tobacco farms that have been underworked by their owners, usually Mugabe’s cronies who were given the lands after their being seized from the white owners in 2000. Zimbabwe is the fifth-largest tobacco exporting country in the world and China has the largest number cigarette users on earth, buying 54 percent of Zimbabwe’s tobacco annually.

While China’s economic reach to Zimbabwe becomes deeper, it also faces an enormous political risk. For example, the sudden enforcement of the indigenization law in March 2016 endangered the interests of all foreign investors, China in particular. Passed in 2008, the indigenization law stipulates that all “foreign and white-owned companies with assets of more than $500,000 should cede or sell a 51-percent stake to black nationals or the country’s National Economic Empowerment Board.” Due to complaints from foreign investors and the Zimbabwean need to attract foreign investments, the law was never seriously enforced. But in March 2016, the Ministry of Youth, Indigenization, and Economic Empowerment announced that the government had decided to implement the law and required foreign companies to submit their stake transfer plans by April 1 or face the risk of closure. A month ago, the Zimbabwean government already closed diamond mining companies owned by Chinese (Anjin and Jinan), Russians, South Africans, and Emiratis, as an effort to enforce the indigenization law.

Some argue that the economic downturn, the result of decreasing commodity prices in the last few years, led Zimbabwe to strengthen the indigenization law. As the eighth largest diamond-producing country, Zimbabwe enjoyed a tax income from diamond exports as high as $84 million in 2014. However, that number nosedived to $23 million in 2015, which may have triggered the government to take over foreign mining businesses. Others have suggested that the mounting factional war within Zanu-PF may be the culprit of the sudden indigenization move. Patrick Zhuwao, the indigenization minister and nephew of Mugabe, is part of Grace Mugabe’s Generation 40 or G40 faction, which may be interested in channeling the localized businesses and profits to buttress the faction and Mugabe himself. In contrast, the finance minister, Patrick Chinamasa, who is associated with Vice President Mnangagwa’s faction, tried to assure the foreign-owned financial institutions in Zimbabwe that they were compliant and would not face censure.

In any case, China expressed its unhappiness to Zimbabwe, both rhetorically and through action – or, more precisely, a lack of action. When Harare saw a large wave of street protests in April 2016 over Mugabe’s unwillingness to step down, and as Mugabe watched his country’s economy slip down the slope, his “all-weather friend” kept silent, at least for a while. Some thought that Beijing might be teaching a lesson to Harare, while others argued that China was actually preparing for a post-Mugabe or even post-Zanu-PF scenario by not annoying the oppositions too much.

Mixed Local Attitudes Toward China

China’s risk in Zimbabwe is also reflected in how the Zimbabweans view China. A welcoming public may help protect China’s interests and signal China’s soft power status, while a dissenting public may be a source of political risk, endangering the Chinese economic and political interests.

As in most African countries, China enjoys an overall positive public image in Zimbabwe. In fact, when asked which external power exerted the most influence in their country, 55 percent of Zimbabweans named China, according to newly released Afrobarometer data. This was the largest percentage among the 36 African nations in the survey. This is no surprise, as Mugabe is outspoken in praising the Zimbabwe-China relationship and as the bilateral economic ties are growing strong. But it is still impressive, considering that other Southern African nations such as Lesotho, Swaziland, and Botswana have named South Africa and the Unites States the most influential powers. And it is even more impressive considering that Zimbabwe’s largest trade partner in 2016 is South Africa and that millions of Zimbabweans live and work in South Africa.

But when asked whether China’s economic and political influence is positive or negative, the Zimbabwean response was divided. Forty-eight percent of the respondents viewed the influence as “somewhat / very positive,” while 31 percent answered “somewhat / very negative.” The disapproval rate would place Zimbabwe fifth among 35 surveyed African nations. Moreover, 30 percent of Zimbabweans did not think that China’s economic assistance to Zimbabwe was helpful, while in contrast the figure was as low as 6 percent in Cote D’Ivoire.

Unsurprisingly, Chinese investments and aid in building local infrastructure have helped improve China’s image in Zimbabwe. Forty-one percent of respondents said investment in infrastructure and business is the contributing factor to their positive image of China, while 31 percent also believed that the low cost of Chinese products was helpful. The problem is, for many Chinese products, low cost may equal low quality. Forty-eight percent of Zimbabweans named the quality of Chinese products as the contributing factor shaping their negative view of China. Eighteen percent of Zimbabweans also disliked China due to its “extraction of resources from Africa,” a percentage ranked fifth after Ghana, Madagascar, Gabon, and Sierra Leone.

How much of the negative image of China is attributed to the citizens’ dislike of Mugabe is unknown. China has long been criticized for strengthening autocratic rule in Africa through economic dealings and financial aid, although, in the Zimbabwean case, it is hard to prove whether the country would have fared better without the China variable. But Mugabe’s opponents surely find China an easy target to vent their anger at Mugabe. “[The Chinese] have contributed nothing of value except to aid a corrupt and repressive political system while looting away our national resources,” writes Willias Madzimure, secretary for international relations of PDP, a small opposition party.

Post-Mugabe Scenarios

An aging president hoping to win his sixth reelection at the age of 94; a ruling party factionalized between G40 and those led by the vice president; a faltering economy that has resorted to nationalizing foreign investments for survival; and the rising tide of online and street protests – the combination makes Zimbabwean politics complicated and uncertain for the next few years. China’s political and economic stake in Zimbabwe is high enough to demand a close watch on developments. At the same time, China has to be careful weighing up its options, because whatever it does is being watched by other African states, who will take China’s actions in Zimbabwe as a reference to what may happen in their future.

China seems to have opted to continue its support of Zanu-PF. Not long after China showed its displeasure over Mugabe’s indigenization move, it shelled out a $5 billion financial rescue package to fund agriculture and housing projects, which would be very helpful to Zanu-PF’s reelection bid. Apparently, the deal was finalized during a ministerial delegation’s trip to Beijing led by the G40 frontman, Local Government Minister Saviour Kasukuwere. Some compared Beijing’s package with the “Lima Plan,” the West-backed international financial institutions’ solution to the Zimbabwean economic crisis, which includes a financial package of $2 billion under the condition that Zimbabwe clear its $1.8 arrears to the IFIs. Struck in Peru on October 2015, the deal was welcomed by Finance Minister Chinamasa, but it has been prevented by Grace Mugabe’s G40 group.

With more cash to be pumped into the national coffer, Mugabe may regain his ability to sustain patronage to supporters. The military is expected to stand with the Mugabe-led civilian government due to their ideological and institutional links. But without sufficient monetary support, Mugabe can’t guarantee a loyal military force. Also, farmers and the youth are important voting populations, and the Chinese financial package for agriculture and housing would help Mugabe win support of these groups.

However, China may already see a more favorable scenario. Letting G40 and Mnangagwa fight each other in a post-Mugabe scenario would be too risky. Rather, through negotiation and economic leverage, China may try to ensure a peaceful power transition while the aging president is still active enough to make such an important decision. The question is who will receive China’s support. Some reports argue that Mnangagwa, who received his ideological and military training in Beijing and Nanjing in the 1960s, may be China’s preference of China, but at this moment, the black box is still closed.

The strongest opposition party to Zanu-PF so far is the Movement for Democratic Change-Tsvangirai (MDC-T) led by Morgan Tsvangirai, who managed to win enough votes to share power with Mugbabe as prime minister from 2009-2013. China’s relations with Tsvangirai and the party he leads are very practical. Despite Tsvangirai’s outright criticism of Chinese investments and Beijing’s backing of Mugabe during the 2008 electoral campaign, he was invited to visit China after becoming prime minister in 2012 – perhaps because China saw a possibility that he might win the presidential election in 2013. But instead of smoothing ties, during the 2013 campaign, he vowed to crack down on Chinese mining companies, arguing that they are not helpful to Zimbabwean economy. In the 2018 election, Tsvangirai would be facing either Mugabe or Mnangagwa, and his chance of winning may be even less certain than in 2013. It is doubtful that China would court him again as it did five years ago.

Meanwhile, former Mugabe vice president Joice Mujuru, after leaving Zanu-PF, formed her own party, Zimbabwe People First (ZimPF), and has supported peaceful resistance to Mugabe’s rule. As the 2018 election draws close, Mujuru clearly stated her willingness to compete. “Mugabe represents the past, represents failures, whereas I, Mujuru, am the bridge to forming the next government that will bring change to Zimbabwe and Zimbabweans,” she recently told the public. As much as Mujuru tries to paint herself as a different political figure from Mugabe, however, her entire political career up till 2014 was with Zanu-PF, which becomes a liability for her future electoral campaigns.

The potentially worst scenario for China is a rulerless Zimbabwe, with neither of the Zanu-PF factions winning over each other, a destructive but weak opposition party force, uncontrollable social turmoil, and the military stepping in politics. In that case, it would take years for the country to recover a functional government to run the economy. China’s existing investments and future interests in a failing Zimbabwe would all come to an end. China needs to avoid the worst scenario, and it seems that hoping for another term of a Zanu-PF-led Zimbabwe, headed by either of the two factions, would be the best way to do so.

Wang Xinsong is an associate professor at Beijing Normal University School of Social Development and Public Policy. He specializes in Chinese politics and China’s role in international development. He leads the Shi Jian (世见) Global Affairs and Development Team, a research initiative to study China’s role in global affairs.

Thanks to Aleksandra Radjenovic and Mitchel Chiviru for early comments on this article.