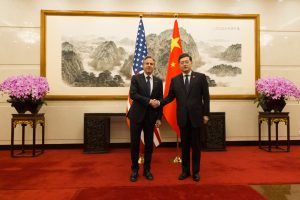

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken made his much-anticipated first trip to China on June 18-19, well over two years after he first assumed office. His visit came amid increasing worries – especially by other countries in the Indo-Pacific region – that China and the United States have entered into a new Cold War. With tensions riding at a post-Tiananmen high, Blinken’s visit provided a small sign of hope that regular diplomatic engagements would resume. But how far can diplomatic visits go in altering the trajectory of China-U.S. relations?

In this written Q&A, The Diplomat’s Shannon Tiezzi asked Ali Wyne, a senior analyst at Eurasia Group’s Global Macro-Geopolitics practice, about the future prospects for China-U.S. relations. Wyne, who is also the author of “America’s Great-Power Opportunity: Revitalizing U.S. Foreign Policy to Meet the Challenges of Strategic Competition,” notes that “the United States and China will find it difficult to establish guard rails until and unless they accept that they are fated to coexist.”

This was Blinken’s first trip to China, and came after some major bumps in the road. In that sense, the visit itself seems like an achievement. On the other hand, no one expected the visit to make progress on entrenched issues of China-U.S. contestation (nor did it). How significant was Blinken’s trip in the long-term sense?

It was a significant trip, as Secretary Blinken became the first top U.S. diplomat to visit China in five years. It will not – and was not expected to – change the fundamentally and intensely competitive nature of U.S.-China relations, but it will give the two countries an opportunity to increase the frequency and broaden the scope of high-level dialogues. Amid strategic distrust, diplomacy serves an important demonstrative purpose: to persuade competitors that, even if a given exchange produces only modest progress, serious and constructive dialogue can occur, be sustained, and suggest pathways to a modus vivendi. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, and Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry are all likely to visit China by year’s end.

Unfortunately, though, while diplomatic respites – such as that which followed U.S. President Joe Biden’s meeting last November with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping – may interrupt the deterioration of U.S.-China relations, they do not alter that trajectory. In addition, because of developments that transpire between them, ties are in worse condition when each respite begins.

Looming over every subsequent interaction between U.S. and Chinese officials will be a set of calcifying, mutually reinforcing judgments: The United States believes that China seeks to replace it as the world’s preeminent power, while China believes that the United States seeks to contain its technological progress and, therefore, its economic development. The more strenuously each tries to reassure the other to the contrary, the more confident the other becomes in its conclusion.

Blinken’s trip went ahead despite continued rhetorical sniping from both sides in the immediate lead-up and aftermath. Have we entered a phase where Beijing and Washington can be openly critical of each other and still engage in dialogue – similar to the balance Japan has struck in the past few years?

The United States and China have been in such a phase for a while, but they criticize each other with increasing openness, and the ability of dialogue to stabilize their relationship is declining. Thus, more and more members of Congress believe that China poses an existential threat to the United States. Meanwhile, according to the Chinese readout of Secretary Blinken’s meeting with China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, “Wang demanded that the United States stop playing up the so-called ‘China threat,’ lift illegal unilateral sanctions against China, stop suppressing China’s scientific and technological advances, and not wantonly interfere in China’s internal affairs.”

What are the prospects for China and the United States to – in the Biden administration’s words – put in place meaningful “guard rails” in their relationship? Some analysts have suggested that the Cold War is actually a useful model in this regard, given the various agreements and tacit norms, especially in the military sphere, that the U.S. and Soviet Union developed to keep their competition in check.

The most dangerous period of the Cold War was between World War II and the Cuban Missile Crisis, when Washington and Moscow were probing to identify each other’s red lines. After they walked back from the brink of nuclear war, they constructed a de-escalation apparatus to stabilize their rivalry. The United States and China have been unable to establish a comparable structure for reasons that Kurt Campbell and I discussed in an August 2020 article for Lawfare, and military-to-military dialogue is growing more impoverished.

At least two other phenomena militate against the establishment of guard rails. First, economic interdependence, while still substantial, is diminishing, with the United States and China each increasingly viewing it not as an imperfect source of stability in their relationship, but as a potent vector of vulnerability. Second, various people-to-people exchanges are declining. According to the State Department, there were roughly 350 Americans studying in China in the most recent academic year, down from almost 15,000 a decade earlier. The U.S. press corps in China is far smaller than it was before the start of the coronavirus pandemic, limiting Americans’ window into and ability to understand developments there. To give one more example, there were 94 percent fewer direct commercial flights from the United States to mainland China in April 2023 than in April 2019.

The U.S. readout of Secretary Blinken’s meetings in China encouragingly noted that “both sides welcomed strengthening people-to-people exchanges between students, scholars, and business.” One hopes, in addition, that U.S. and Chinese defense officials will establish and/or restore working groups to explore how U.S. forces and People’s Liberation Army (PLA) forces should interact when in close proximity and how they should proceed in the event of an incident between them in the air or at sea.

Absent – and perhaps even after – a security crisis, the United States and China will find it difficult to establish guard rails until and unless they accept that they are fated to coexist. To do so, they will each have to internalize a pair of uncomfortable likelihoods: first, that the other is likely to endure, and second, therefore, that strategic competition between them is unlikely to produce a clear “victor.”

Blinken’s visit to China contrasted sharply with Beijing’s refusal to arrange a meeting between U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and Chinese Minister of Defense Li Shangfu while both were attending the Shangri-La Dialogue. How far can the two sides go in stabilizing their relationship without military-to-military contacts?

They cannot go very far. It is difficult, if not impossible, to have a stable bilateral relationship if each country believes that the other is actively trying to undermine its security. Recent near-misses between U.S. and Chinese military assets underscore the risk of inadvertent escalation – a risk that will grow as the Indo-Pacific region becomes more congested. It is concerning that China rejected Secretary Blinken’s proposal to establish a communications channel to manage potential military crises, and the broader degradation of military-to-military exchanges diminishes Washington’s ability to interpret the PLA’s recent maneuvers in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait.

Even while Blinken was in China, Chinese Premier Li Qiang was starting a trip to Germany and France. How is Beijing’s approach to Europe different from its diplomatic policy toward the United States?

China recognizes that a permanent rupture in relations with the world’s preeminent power would undercut its long-term strategic outlook. It also worries that rebuffing diplomatic overtures from the United States would advance transatlantic alignment on competing with China, potentially by increasing the European Union’s willingness to restrict the presence of major Chinese technology companies such as Huawei and embrace export controls that narrow Beijing’s path to greater semiconductor self-sufficiency.

Even so, China recognizes that the EU is unlikely to be as willing as the United States to subordinate economic considerations to national security ones, in part because Washington, as the world’s leading power, discerns much higher stakes in Beijing’s resurgence than Brussels: It sees China as the principal challenge not only to its position in world affairs, but also to the order that it underpins. China is more optimistic that it can restore a baseline of stability to its relations with the EU, even as its deepening ties with Russia have significantly undermined its standing in Brussels.

It will tap into the concerns of high-ranking EU officials and prominent European leaders including French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz about the emergence of “a new Cold War.” It will also expand its outreach to major European multinational corporations, which worry about losing their access to the world’s largest consumer market.