In the wake of the passing of South African great Nelson Mandela, the United States has turned its attention to another Nobel Peace Prize winner — Liu Xiaobo of China. In a statement marking the fifth anniversary of Liu’s detention, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry called on China to release Liu Xiaobo as well as his wife, Liu Xia, who is currently under house arrest.

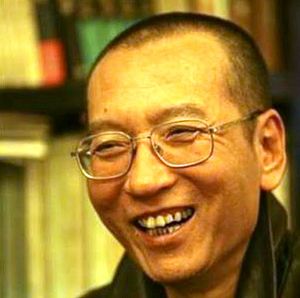

Liu Xiaobo was detained in 2008 for his role as co-author of Charter 08, a democratic manifesto that called for the Chinese government to protect the freedom of expression assembly, and religion, as well as demanding the separation of powers and a legislative democracy. Liu, who also participated in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, was sentenced in 2009 to eleven years in prison for “inciting subversion of state power.” Despite China’s vehement protests, Liu, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 “for his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.” Since then, Liu has become a symbol of the plight of China’s dissidents. His wife, Liu Xia, has also been under house arrest since 2010.

In his statement, Kerry said that “the United States is deeply concerned that the Chinese authorities continue to imprison Liu Xiaobo, as well as other activists, such as Xu Zhiyong, for peacefully exercising their universal right to freedom of expressions.” He went on to “strongly urge the Chinese authorities to release Liu Xiaobo” and his wife.

In response, China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesman Hong Lei dismissed the claims that Liu Xiaobo or Xu Zhiyong were deserving of sympathy. Hong said that both men had “violated Chinese laws and they are to be punished by Chinese laws.” On a deeper level, Hong rejected the idea that U.S. politicians have any right to speak about China’s human rights situation. “I want to suggest that only the 1.3 billion Chinese people have a say on China’s human rights,” said Hong, adding “We hope the US can bear in the mind the overall interests of bilateral relations.” The message was clear: there’s nothing unusual about Liu’s case, and even if there were, it’s none of the United States’ business.

This is typical of the back-and-forth between the U.S. and China over human rights. The U.S. will call attention to an issue or even specific person, and China will respond by denying the “groundless accusations.” To China, any human rights concerns raised by the U.S. are automatically assumed to come from a desire to undermine China both domestically and on the world stage. While serving as Assistant Minister of Foreign Affairs, Cui Tiankai asserted in a policy article that human rights issues were being used to encourage a long-awaited “color revolution” in China. “Apparently,” said Cui, “some Americans have never stopped their attempt for a ‘peaceful revolution’ in China.” Cui, it should be noted, has since gone on to become China’s Ambassador to the United States, meaning his views were hardly unorthodox.

Given this reaction, it’s worth wondering what good U.S. statements like Kerry’s actually accomplish. U.S. politicians have been calling for the release of Liu Xiaobo since he was first imprisoned, with absolutely zero effect. And Liu is not the only Chinese citizen to be mentioned by name as of particular concern for the U.S. Hillary Clinton, in a 2011 speech, specifically demanded “the release of Liu Xiaobo and the many other political prisoners in China, including those under house arrest and those enduring enforced disappearances, such as Gao Zhisheng.” Later in the same year, Clinton also noted the U.S. was “alarmed” over “the continued house arrest of the Chinese lawyer Chen Guangcheng.”

None of these three men (Liu Xiaobo, Gao Zhisheng, and Chen Guangcheng) were released by the Chinese government. The only member of the list not currently in custody is Chen Guangcheng, who famously escaped from house arrest and made his way to the U.S. Embassy in Beijing. Chen was emphatically not released by the Chinese government, which reacted with outrage to the appearance of a Chinese citizen within the U.S. Embassy.

U.S. calls to release political prisoners, despite their frequency, have little effect. Statements like Kerry’s are never followed by concrete action on the Chinese side, and the U.S. has yet to back up its “strong urgings” with concrete action. Rather, such statements are an easy way for the U.S. to remind everyone that it cares about human rights, without actually suffering any political or diplomatic consequences. Perhaps these statements lend some moral support to the named dissidents, but even that might be unintended. It’s doubtful, for example, that the U.S. wants to inspire other dissidents to follow Chen Guangcheng’s example. In addition, remarks from the U.S. also make it easier for the Chinese government to paint political prisoners as Western “pawns,” as state media called Chen Guangcheng.

Even human rights advocates have called the strategy into questions. As Perry Link told NPR in an interview following Chen Guangcheng’s arrival in the U.S., “the problems of human rights in China are not problems of one or two people whose cases have to be ‘resolved,’ quote-unquote. It’s a very deep, underlying long-term problem and we should view it that way.” As a result, the U.S.’s strategy of highlighting one or two names for emphasis each year accomplishes little other than giving U.S. officials something to point out when they are criticized for ignoring human rights.