What will it take for the Chinese government to view human rights lawyers and defenders within China not as threats, but rather as well-intentioned citizens who want to help their nation? This question, posed by U.S. Congressman Robert Pittenger (R-NC), lay at the heart of a recent congressional hearing on human rights defenders in China.

Beijing has consistently justified human rights abuses in the pursuit of “social stability,” argued Dr. Sophie Richardson of Human Rights Watch. She highlighted the role of “civil society groups and advocates,” who “continue to slowly expand their work despite their precarious status,” as well as the “informal but resilient network of activists,” which “monitors and documents human rights cases as a loose national ‘weiquan’ (rights defense) movement. These activists endure police monitoring, detention, arrest, enforced disappearance, and torture.”

International observers are concerned that the regime increasingly targets dissidents—particularly ethno-religious minorities—by accusing them of supporting the “three evil forces” of terrorism, separatism, and extremism, and then arresting them on charges of endangering state security. In a country that lacks transparency and an independent judiciary, how can we be confident that justice is actually served?

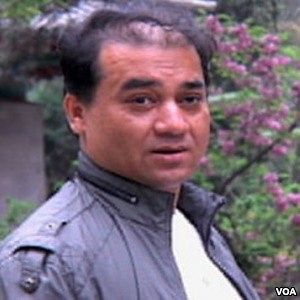

One recent victim of this approach is a professor at Beijing’s Minzu University. Uyghur economist Ilham Tohti is known for his moderate, pragmatic writings on various aspects of Uyghur society. He founded the website “Uyghurs Online” in 2005, envisioning it as a platform for cultural and social exchange between the Han and Uyghur peoples. According to Ilham Tohti, we “should not fear disputes and disagreements, but rather the silence and suspicion that exist within hatred.” He was formally arrested on February 20, charged with separatism, and denied access to his attorney. Tohti’s daughter, Jewher Ilham, who was a witness at the hearing, described her father’s “sole ‘crime’… [as] simply advocating human rights and equitable treatment for the Uyghur people.” Yet, he has little chance in a Chinese court—less than 1%, according to official figures—-of proving his innocence if he is brought to trial.

Equally grim are the cases of other prominent human rights defenders. Xu Zhiyong co-founded the New Citizens Movement to create partnerships between ordinary citizens and human rights defenders in the peaceful pursuit of civil and legal rights. He was sentenced to four years in prison on January 26. Lu Xia, wife of Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, faces deteriorating physical and mental health under house arrest in Beijing. Far more serious is the case of Cao Shunli: she’s dead. The civil society activist pressured Beijing to engage with domestic human rights defenders during China’s UN periodic human rights review process. When she attempted to fly to Geneva on October 22, authorities detained her at the airport and eventually charged her with “picking quarrels to create disturbances.” Her health deteriorated dramatically during her detention. She slipped into a coma, and died shortly after her release on “humanitarian” grounds.

As China gains political and economic clout abroad, it is less tolerant of what it perceives as profoundly unequal exchanges with established powers. At a recent talk in Washington, Dui Hua Foundation founder John Kamm noted that the Chinese government has begun to rebuff prisoner lists during bilateral human rights dialogues. It may also insist in the coming years to work fully within the United Nations framework to address human rights, rather than engage individual nations on the sidelines. Indeed, China takes advantage of “flawed international institutions” to deflect attention from its human rights record and thus subvert the interests of Chinese citizens, argued Dr. Teng Biao, human rights lawyer and co-founder of the New Citizens Movement.

The United States and its democratic partners need to think more creatively about how to best promote and protect human rights as well as achieve the release of political prisoners. U.S. leaders must continue to speak out publicly and privately in meetings with their Chinese counterparts to make our principles and aspirations clear. However, we should also increase the number of academic exchanges and Track II dialogues to constructively engage China at all levels of society. Through measures designed to build trust, enhance transparency, and share best practices, the United States can make it clear to China that we have mutual interests in elevating human rights. For example, legal and judicial exchanges have already provided China with the resources and knowledge it needs to make positive legal reforms to its criminal code.

China acts—and will continue to act—in its own national interests. The U.S. must convince China that a sustained focus on human rights does not constitute diplomatic containment. On the contrary, the United States welcomes a stable, peaceful China that treats its citizens, neighbors, and other nations around the globe with respect and dignity.

In places like the United States, Europe, “and in every corner of the world where the light of freedom shines, while the struggle for human dignity continues,” asserted Dr. Teng, “we [the Chinese people] will not be forgotten.” The United States must work in concert with its global partners—as well as with the leadership in Beijing—to raise the profile of human rights defenders under threat, so that they don’t befall the same fate as Cao Shunli.