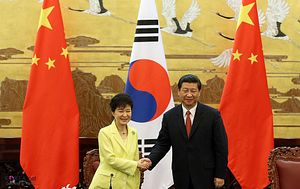

Between North Korean threats of a “new form” of nuclear test and South Korean reports of increased activity at Punggye-ri, there are growing concerns that Pyongyang may attempt its fourth nuclear test during U.S. President Barack Obama’s visit to Seoul at the end of this week. Apparently, South Korean President Park Geun-hye is concerned enough at this possibility that she called Chinese President Xi Jinping to discuss the matter — and asked for China’s help in handling its recalcitrant ally.

South Korea’s Yonhap News reported that Park called Xi on Wednesday morning to ask him to help prevent a possible North Korean nuclear test. According to Yonhap, Park told Xi that another nuclear test would be a “nuclear domino” that would spark an arms race in the region. To prevent this, she asked Xi to persuade Pyongyang not to undertake another nuclear test. Specifically, she said that China should use its status as North Korea’s largest source of both trade and foreign aid in order to influence Pyongyang’s decision.

China’s Foreign Ministry addressed Park and Xi’s phone conversation in a regular press conference. Spokesman Qin Gang said that Xi “reiterated China’s firm commitment to realizing the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” Qin added that Xi and Park “agreed to remain [in] close communication, coordination and cooperation on the issue of the Korean Peninsula.”

Qin did not specifically address the possibility of a nuclear test, but he repeated China’s customary position that “relevant parties should keep calm [and] exercise restraint.” He also expressed China’s opposition “to any action that may further escalate tension in the Korean Peninsula.”

A fourth nuclear test by Pyongyang, particularly one timed to correspond with Obama’s visit to Seoul, would certainly fall under the category of actions that escalate tensions for the Korean Peninsula. However, despite what foreign leaders think, there are clear limits to China’s influence in North Korea. Western diplomats believe that Beijing spent a lot of effort trying to dissuade North Korea from its nuclear test in 2013, to no avail. The timing of that test was particularly awkward for Beijing, as it came in the interim period between Xi Jinping’s taking over leadership of the Communist Party of China and his actually assuming the presidency. That Beijing was unable to even persuade North Korea to delay the test suggests that China’s control over Pyongyang (always precarious) has slipped.

Western analysts often argue that China could do much more to control North Korea, particularly by punishing Pyongyang’s bad behavior through heavy trade sanctions and decreases in aid. However, China’s own national interests place strict limits on how far Beijing it willing to go in punishing North Korea (answer: not very far). China is serious about not wanting North Korea to become a nuclear state, but Beijing long ago made the decision that a nuclear North Korea is slightly less onerous than a collapsed North Korean state. To date, Beijing’s fears that cutting trade or aid to its neighbor would destabilize the Kim regime have outweighed its displeasure over nuclear and missile tests.

Worse, Pyongyang knows this, allowing North Korean leaders to effectively thumb their noses at Beijing by carrying out actions despite China’s direct opposition. Pyongyang understands that its ties with China are not based on Beijing’s goodwill, but on the far more sturdy base of Beijing’s self-interest. Thus, Beijing’s approval or disapproval is fundamentally meaningless for North Korea as long as China’s leaders keep their essential strategic calculus unchanged.

To really enlist China’s help in preventing another nuclear test, President Park would have to first convince Beijing that the collapse of North Korea (and the eventual reunification of the Korean Peninsula) would not harm China’s self-interests. Until China is willing to risk the collapse of the Kim regime, all its warnings will be essentially meaningless — and North Korea knows it.