As my colleague Shannon wrote on Wednesday, the annual U.S.-China dialogue has been held in Beijing, with the two sides trying to identify areas for common ground. This is becoming increasingly difficult as more and more issues crop up on which the two powers take opposing sides. Beijing and Washington seem to be seeking to gain ground on common issues like trade and North Korea in order to lessen tension around Chinese territorial disputes and accusations of state-sponsored cyber-attacks. Success at these talks will not be measured in the number of issues over which they are able to agree, but in their ability to maintain an ongoing and constructive dialogue while their respective allies exacerbate tensions in an increasingly volatile region.

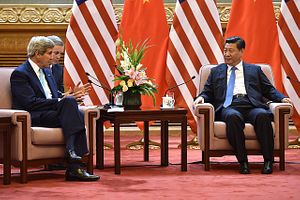

One area where able to find a modicum agreement will be North Korea, strangely enough. Usually Pyongyang’s only reliable ally, North Korea has become increasingly isolated from China this year. As Chinese President Xi Jinping officially opposed North Korea’s nuclear program during a widely covered state visit to Seoul last week with South Korean President Park Geun-hye, the U.S. and Chinese sides also appear to be on the same path this week. A senior U.S. State Department official at the talks said that both countries were “refining [their] respective strategies. We are expanding the places where we can do more together, and we’re delving down more deeply in the conversation about what may work and at what risk and at what cost.” The official also speculated that Xi’s visit to Seoul last week before visiting Pyongyang show’s China’s increased exacerbation. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said the two had discussed different options to convince Pyongyang to abandon its nuclear program, while China’s top diplomat said both sides could do “more things to relax the situation.”

Discussions on trade may not have been as positive, but they were still constructive. U.S. Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew accompanied Kerry on the trip, and has raised questions about certain recent aspects of China’s economic policy, while calling for more openness to foreign investment. Specifically, Lew questioned why China had allowed the yuan to weaken against the dollar. The People’s Bank of China increased its foreign reserves to $3.9 trillion in the first quarter this year, which caused the yuan to decline 2.4 percent versus the dollar. However, Lew made sure to emphasize U.S. interest in mutual investment, and that it looked “forward to having opportunities for U.S. businesses to participate and contribute to China’s economy.” The two sides are also reportedly making steady progress on the Bilateral Investment Treaty in order to further facilitate bilateral trade in excess of $520 billion.

While those two issues will likely be the highlights of this year’s dialogue for both countries, significant problems in their relationship remain open. The U.S. has made cyber security a key issue since it accused five People’s Liberation Army officers in May of online espionage, which caused China to suspend participation in the U.S.-China Cyber Working group. Leading up to this week’s talks, U.S. officials said “One of the fundamental differences is on this question of the acceptability of cyber-enabled economic espionage, which the United States does not conduct. We need to come to a clear understanding with the Chinese about that. That is going to be essential to resolving our concerns about Chinese behavior.” On Monday, in response to the U.S. statement, Chinese Assistant Foreign Minister Zheng Zeguang said “We believe the U.S. side deliberately fabricated the facts… This proves the U.S. side is not sincere in resolving Internet security issues through dialogue and cooperation.” Kerry said he did not discuss the Chinese hacking of U.S. information concerning government employees, but that “We’ve been clear on larger terms that this is an issue of concern.”

While the issue of cyber security did not gain much traction during this week’s talks, it is at least an issue relegated to bilateral concerns. The issue that was the most intractable this week was territorial disputes, and the U.S. backing of Japan’s reinvented military posture. U.S. officials tried to address concerns over the territorial issues earlier this week, saying “It is our observation that ambiguity about claims can be destabilizing and can lead to confrontation and even conflict,” and that it will call on all parties to clarify claims in accordance with international law. However, China is unlikely to change its claims (particularly in the South China Sea) without the U.S. intervening much more than it has recently. At the same time, the U.S. cannot afford to abandon its rhetorical support of its Southeast Asian allies. What is left will be a holding pattern where both states agree that while no common ground is currently available, the disagreement is not large enough to affect other issues where progress is being made.

Japan’s recent change in its interpretation of collective self-defense is a more fundamental regional issue, and one in which the Chinese and U.S. positions are diametrically opposed. Despite statements aimed at easing Chinese concerns, U.S. support for a normalized Japanese military is primarily driven by China’s own recent militarization. While the U.S. and Japan state that this change will help include Japan’s significant military force in regional peacekeeping operations, and that the region’s primary threat is North Korea, the Chinese see themselves firmly in the crosshairs. The Chinese Communist Party cannot drop its recent spate of vitriolic rhetoric against Japan and its wartime past without appearing weak domestically. This week’s dialogue is unlikely to bridge these divergent views. At best they avoided the issue where they could, in the hopes of continued progress elsewhere. The main problem that U.S. and Chinese officials grappled with is that the scope of cooperation is continually shrinking, while the problems are moving beyond the stage where bilateral solutions are feasible.