A fatalistic dread is sweeping through Hong Kong amid fears that a violent confrontation between Chinese forces and supporters of the pan-democrats and Occupy Central movement, demanding full universal suffrage by 2017, is imminent with neither side prepared to give ground.

Antagonizing the mood was the deployment of troops and armored personnel carriers from the mainland over from across the border last week as the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC) met in Beijing to decide on how the territory chooses its next leader.

After a week-long meeting the Standing Committee endorsed a framework for democracy with 170 delegates casting a unanimous vote which Beijing would like to consider historic.

“Since the long-term prosperity and stability of Hong Kong and the sovereignty, security and development interests of the country are at stake, there is a need to proceed in a prudent and steady manner,” the committee said.

But the framework falls far short of loud and aggressive demands by pro-democracy activists in this city of 7.2 million people.

Any candidate standing for election in the territory must be a patriot and approved by Beijing through a nomination committee. The number of candidates contesting the poll would be limited to two or three. And the size of the committee will remain the same as the existing 1,200-member election committee consisting largely of Beijing loyalists and vested business interests.

It was a decision widely anticipated by Benny Tai Yiu-ting, a senior figure within Occupy Central, who is threatening an agenda of civil disobedience and the occupation of the central business district by thousands of supporters.

“The central Chinese and Hong Kong governments and pro-democracy elements seem unwilling or unable to compromise; this raising the likelihood of triggering the long awaited ‘occupy central exercise,’” said risk consultant Steve Vickers, of Steve Vickers Associates.

“Despite statements that any such disobedience movement will be peaceful there is considerable concern in the local community that civil disorder would negatively impact Hong Kong businesses and the city’s reputation.”

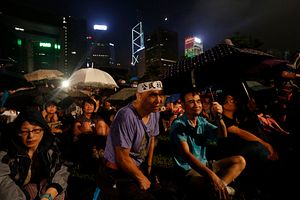

A showdown immediately after the release of the statement was expected with Tai Yiu-ting urging his supporters to gather outside the chief executive’s office as the Standing Committee’s decision was made public.

However, the soft-spoken Hong Kong law professor had also stressed this was not the start of the occupation of Central. That start date remains shrouded in secrecy amid warnings from Beijing that it expects “something will happen” and criminal prosecutions would follow.

Antagonism between Hong Kong and Beijing over a timetable for democracy has been a constant source of friction since the former British territory was retuned to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, with major protests accompanying the anniversary each July 1.

But observers say the make-up of protests has changed with a substantial increase in the number student organizations taking part and agitating for change. Among them is Scholarism, founded by Joshua Wong in 2011 to fight the proposed “Moral and National Education” curriculum.

Their inclusion has added shades of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 to the current stand-off as they argue against mainland attempts to establish its version of a patriotic, pro-Communist sense of history for Hong Kong.

No-one is questioning Chinese sovereignty over Hong Kong but ahead of this year’s July 1 march almost 800,000 ballots were cast in an informal referendum on how the next chief executive should be chosen. It was a resounding victory for one person one vote.

Tens of thousands of people then took to the streets, prompting an ominous warning from Chen Zuoer, former deputy director of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, who said there would be bloodshed if Occupy Central refused to back down.

In an interview with RTHK he deployed rhetoric reminiscent of the Cold War, claiming the Occupy movement was being “manipulated by Western countries to overthrow a regime.”

He also said Beijing “would not tolerate such action.”

Before the handover, the British struck agreements with the Chinese government over the implementation of the Basic Law – essentially a mini-constitution – mandating universal suffrage by 2015 and the election of a chief executive, which was subsequently pushed back to 2017.

Current chief executive, Leung Chun-ying was selected in 2012 by the 1,200-member committee. In 2017, however, Hong Kong residents were expecting to be able to vote for their leader but Sunday’s decision effectively means nothing has changed.

Hong Kong-based barrister Kevin Egan said two articles in the Basic Law had not helped the current climate. Article 26 guarantees all citizens in the territory the right to vote and to contest elections. But this is a general rule and there are arguments it can be overridden through Article 45, a specific rule, which he said was also vague and open to interpretation.

“Article 45 has so many holes in it I can drive a truck with a loaded trailer through it,” he said. “If it was a Will or a Deed of Trust it would probably be held by the courts to fail for uncertainty due to the inexactitude of language.”

Essentially, Article 45 allows for universal suffrage. However, Egan said interpretations meant that it could be used to support the implementation of a traditional Western-style democracy or universal suffrage from a Chinese perspective, underpinned by absolute control by the central government.

This goes to the core of the dispute and Beijing’s requirement that candidates for chief executive must obtain the support of more than 50 percent of a nominating committee in order to stand.

In the court of public opinion legal arguments over interpretations of the Basic Law are wearing thin, with political activists from both sides hardening their stance. This has become self-evident over the past month.

In late July, the pro-democracy website House News was closed by its founder who said he no longer felt secure. In mid-August, the anti-Occupy Central group, the Alliance for Peace and Democracy held its demonstration and claimed 250,000 people had marched.

That figure was widely disputed, nevertheless the Beijing Times trumpeted: “The mainstream voice has finally erupted.” It said that protest was a response by the silent majority to a minority of extremists in the Occupy movement who were pushing an illegal political agenda.

Last week the Hong Kong Post Office refused to mail leaflets posted by Scholarism that reputedly outlined support for the Occupy movement. That action was justified under laws banning “obscene, immoral, indecent, offensive and libelous writing.”

Then investigators from the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) raided the home of media tycoon Jimmy Lai Chee-ying, founder and chairman of Next Media, a fierce and prominent critic of Beijing. He is apparently being investigated for funding certain members in the pan-democrat camp.

Beijing’s great and well-documented fears are that movements like Occupy Central will spread. Across the Pearl River Delta, activists in Macau are holding their own informal referendum on that territory’s democratic future and supporters attempting to man polling stations have been detained.

Few would expect pro-democracy protests here to reach the same fever pitch that they did in Tiananmen Square 25 years ago, when the authorities responded with a heavy, nasty hand that resulted in the deaths of perhaps thousands and the arrests of hundreds.

But Beijing’s temper is notoriously short and the Occupy Central and the pan-democrat camp are insisting the moral high ground is theirs to hold, giving ordinary Hong Kongers good reason to fear what might happen next.

In a worst-case scenario, Vickers said street riots would either become a real justification or a pretext for police intervention, although he stresses this scenario remains improbable.

“Finally in the unlikely scenario that Hong Kong police cannot contain the situation, a state of emergency may be declared, Chinese national security law might be applied and the People’s Liberation Army could be deployed,” he said.

That scenario remains doubtful; however, such high-level intervention from Beijing is now being discussed as a legitimate means of resolving the intractable and that has only added to the frustration and anxiety that already exist across Hong Kong.

Luke Hunt can be followed on twitter @lukeanthonyhunt