I received quite a lot of feedback on my recent piece “What Can Isaiah Berlin Teach Us About Defense Analysis?,” mostly attacking the simplicity of the artificial dichotomy I proposed when talking about defense/security analysis.

I still think my piece accurately describes the inflexible hedgehog position, and its real and dangerous consequences if taken to the extreme, but I agree with critics that it does not adequately address the model of a strategic hedgehog-tactical fox hybrid. As one thoughtful reader noted:

“The author conflates ultimate goals with tactical flexibility. It is entirely possible to have hedgehog-like views at the geopolitical level (USS/Communism bad, USA good) and still be flexible in the tactics which serve the larger goal (…)There is also nothing inherent in being a hedgehog that demands an immediate action bias. All of this is dependent upon what your one big idea is.”

As the reader points out, a prudential understanding and practice calls for a judicious melding of a synoptic “bird’s eye” view and close empirical examination. The ancient writers Xenophon and Thucydides would be examples of such hybrids, and made great security analysts of their time.

Thucydides is an often talked about author; however, Xenophon (c. 430 – c. 354 B.C.) is a relative neglected ancient writer, but in my opinion one of the prime examples of successfully combining the hedgehog’s unitary vision with the objective empirical analytical skills of the fox.

What makes Xenophon — who has been called “a hippie of the fourth century” — such an interesting analyst to study?

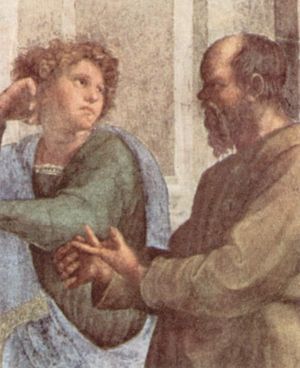

Like Plato (and unlike Thucydides), Xenophon was a student of Socrates, yet as Christopher Bruell notes in History of Political Philosophy, “Xenophon may have been one who pursued the Socratic question of the best way of life without ever coming to accept completely the Socratic answer that the way of life is the philosophic one.”

Thus, in Xenophon we uniquely have a man of action who wanted to experience political life to its fullest, while at the same time being heavily influenced by the unitary vision of Socratic reasoning. In short, Xenophon was not a philosopher but philosophic – probably the best intellectual disposition for a good political analyst, and a great example of of a strategic hedgehog-tactical fox hybrid.

Studying Xenophon may be an especially timely occupation at the moment. With Machiavelli’s political thought making a come back these days (e.g. “Are China’s Leaders Disciples of Machiavelli”, “Why We Should Study China’s Machiavelli”) it is important to note that the notorious Renaissance Florentine was Xenophon’s “most devoted reader,” as Christopher Nadon writes in his book Xenophon’s Prince.

Consequently, if we want to know what Machiavelli is really trying to teach us with his writings, studying Xenophon may provide us with some useful insights to the author of The Prince.

Xenophon’s best book, and the one that I would recommend the most for burgeoning analytical minds, is the Anabasis. The book is an easy read and its writing style is perhaps best compared to the best American presidential autobiography ever written – The Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant.

In the Anabasis, Xenophon sketches out his endeavors to rescue a contingent of Greek mercenaries trapped in the heartland of Persia after a losing a crucial battle, which led to the Hellenes being abandoned by their Persian allies.

The book is said to have inspired Alexander the Great’s successful expedition to conquer the Persian Empire (336-323 BC). In the Anabasis we can see for the first time the practical application of the Socratic unitary vision, one of the best examples of a strategic hedgehog-tactical fox hybrid.

Xenophon combines discussions on mundane tactical and practical matters with strategic observations, such as the never changing nature of competition between ostensible friendly political entities:

“[E]ach side watched the other as though each were enemies, and this, of course, produced more suspicion. Sometimes, when they were both collecting firewood from the same place, or bringing in fodder and such things, fights broke out between them and this too naturally provoked ill feeling.”

Yet he never loses sight of the unitary vision that the Socratic Method is the best way to strategically plan a prudential escape route from the Persian Empire for the 10,000 Greek warriors under his command.

The most important aspect of the Socratic Method is the constant re-examination of one’s own belief system. During his lifetime, Xenophon, surprisingly for a student of Socrates, became deeply infatuated with the closed authoritarian Spartan political system. He saw the usefulness of the Spartan method on the tactical, operational level when waging war (especially after his experience in Persia); however, he never lost sight of the greater (albeit still limited) freedom that the Athenian democratic system provided for analytical minds like himself and the superiority of free inquiry over closed ideological thinking that goes with it.

How he navigated this difficult intellectual double-act is then perhaps the principal rationale why security analysts of democratic societies should study Xenophon and why the hedgehog and fox dichotomy may still be a useful analytical tool in the future.