The late January 2015 summit between President Barrack Obama and Prime Minister Narendra Modi in New Delhi has had unexpected fallout. Beijing has suddenly begun to show a willingness to urgently discuss the resolution of its 4057 km contested border with India. A flurry of statements and opinions that have been released in China since February, discussing a possible resolution to the 60-year-old dispute, suggest changing mindsets in Beijing. For more than a quarter century, China’s India policy has been driven by a consistent stand that resolution of the border issue should be left to future generations. And during 17 rounds of talks at the special representatives level over the past decade, India was happy to go along with the Chinese position.

On the eve of the 18th round (the first under the government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi) of talks in New Delhi on March 23-24, however, there are distinct signs that Beijing is keen to get a move on with the talks. Of course, a complex and historical dispute such as that between China and India cannot be resolved overnight, but recent foreign ministry briefings on both sides have indicated that the process to clarify the line of actual control, as the disputed Sino-Indian border is called, would top the agenda of the Special Representatives talks.

The Global Times, an English newspaper considered close to the establishment in Beijing gave an indication of Chinese thinking in an article in late February. It said: “Identifying the lines of control on each side will be a key step to facilitating the long-stalled process of bringing the disputes to a peaceful resolution. In that case, border standoffs between India and China, such as the one in September last year which started before Chinese President Xi Jinping’s trip to India, should be avoided, helping create a friendly atmosphere to further deepen bilateral ties.” The desire to “identify” the line of control –or line of actual control – has not often been articulated in Beijing in recent years. This could well be a phase during which India and China focus on working towards a resolution of the dispute rather than being content with managing it, as they have done for the past three decades.

What has prompted this change in approach? Undoubtedly, it is the assessment in Beijing that the Modi government is politically much stronger and therefore in a better position to take a final decision on the border issue than the previous two UPA regimes. That the Chinese were cognizant of the new reality was evident very early on in the Modi era. Beijing dispatched its foreign minister to meet the new leadership in Delhi within a month of Modi’s inauguration.

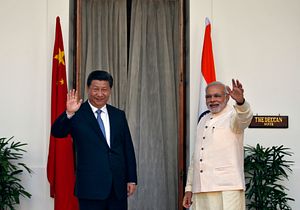

After meeting Modi at the BRICS summit, President Xi Jingping became the first leader of a P-5 nation to make a trip to India in September 2014. Clearly, the Chinese had grasped the changing dynamics in Asia as fast as Modi had done.