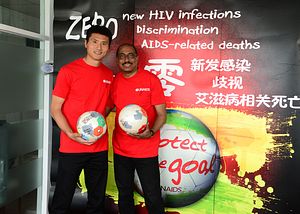

This week, Michel Sidibe, the head of the UN Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) is in China. While there, he and Xinhua president Cai Mingzhao promised to work together to cooperate in the fight against AIDS. In particular, Cai promised that Xinhua would help spread “positive messages” on behalf on UNAIDS, promoting the agency’s “three zeros” goal: “Zero new HIV infections. Zero discrimination. Zero AIDS-related deaths.” Sidibe signed a similar memorandum with Li Congjun, Cai’s predecessor, in March 2014.

The connection between China’s state-run news agency and UNAIDS is just one sign of a transformation in how the Chinese government views and responds to AIDS. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the epidemic was largely ignored by the government – misinformation was prevalent and HIV/AIDS sufferers faced serious discrimination. The epidemic was exacerbated in China due to government-supported blood drives that did not follow adequate sterilization procedures. The drives, which often offered rural residents cash for blood or plasma donations, created so-called “AIDS villages” where a large percentage of residents are HIV-positive.

China’s official government response has changed markedly in the past 15 years. In 2003, China rolled out a program called “four frees and one care” – meaning free blood tests for those living with HIV, free education for those orphaned by AIDS, and free consultations, screening tests, and antiretroviral therapy for pregnant women with HIV or AIDS. In 2011, China announced its “five expands and six strengthenings,” which included efforts to expand HIV/AIDS education, testing, and treatment while also strengthening medical safeguards and the protection of HIV patients’ rights. Today, Premier Li Keqiang speaks openly about the need to do more to fight AIDS, and Peng Liyuan, President Xi Jinping’s wife, is a World Health Organization Goodwill Ambassador for Tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS.

More testing and improved access to treatment has significantly increased the number of Chinese living with HIV who receive treatment. In 2007, the WHO estimated that only 19 percent of HIV patients received treatment. By 2011, nearly 76 percent were receiving treatment. From 2011 to 2013, the number of people receiving treatment for HIV/AIDS skyrocketed from 126,448 to 227,489, according to an official report from China’s National Health and Family Planning (NHFP) Commission submitted to UNAIDS.

According to the same report, as of the end of 2013, there were a reported 437,700 people living with HIV/AIDS in China. Other estimates put the number far higher, at up to 1.5 million. Even if we accept the highest available estimates, the rate of HIV/AIDS infection compared to China’s total population is quite low. However, there are certain regions and areas where the majority of cases are concentrated. As the NHFP report put it, “national prevalence remains low, but the epidemic is severe in some areas and among certain groups.” The districts with highest number of reported cases in Yunnan, Guangxi, Xinjiang, Henan, and Sichuan, according to the report — all of which rank in the bottom half of China’s provinces in terms of GDP per capita.

Sexual transmission remains the primary cause of HIV transmission, accounting for over 90 percent of all new cases in 2013. And new HIV cases are rising particularly quickly among one subgroup – men who have sex with men (MSM). While HIV infection rates have remained static or even dropped among other high-risk groups (including sex workers and intravenous drug users), HIV rates among MSM have increased nearly seven-fold since 2005.

As an acknowledgement that China’s HIV/AIDS epidemic is particularly problematic among gay men, Sidibe visited the Danlan gay men’s network during his visit to China this week. Danlan, which runs a popular dating app for gay men, provides information on the risks of unsafe sex and runs an HIV testing center, all part of a larger campaign to increase awareness of how to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS.

Despite government and NGO efforts, however, the social stigma of being diagnosed with HIV/AIDS remains a serious issue in China. In 2012, a man went public with the story of being denied treatment for lung cancer because of he was HIV-positive. Just last year, China’s state media reported on an eight-year-old boy whose village (including his own grandfather) voted to expel him. The local government promised to make sure the boy would receive medical care and an education.

Such cases of discrimination often stem from ignorance about how HIV is transmitted. It’s precisely here that the UNAIDS-Xinhua partnership can be of use. Spreading information and awareness about HIV/AIDS (especially on how the virus is transmitted) will be crucial to both preventing the spread of HIV within China and alleviating the discrimination faced by people living with the disease.