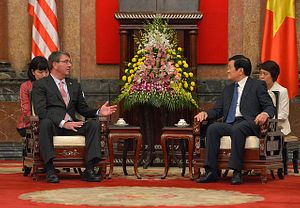

This year is the 20th anniversary of the restoration of U.S.-Vietnam diplomatic relations. Over the years, the two countries have enjoyed a gradual normalization of ties, with a major fillip given recently by the visit of U.S. Defense Secretary Ashton Carter. Washington’s engagement with Vietnam is an important indicator of America’s political commitment in the region. Carter’s visit to Vietnam was also closely followed by policymakers in India – as Carter said at the recent Shangri-La Dialogue, the U.S. is looking for ways to complement India’s Act East policy. U.S.-Vietnam engagement could well act as a catalyst for India’s own growing ties with Vietnam. Over the last few years, Hanoi’s importance has been rising in New Delhi, owing in part to the latter’s Act East policy, and in part to energy security concerns and Vietnam’s geostrategic importance in maintaining regional balance.

Starting in the early 1960s, India has steadily built political ties with Vietnam, regarding the country as India’s “most trusted friend and ally.” Notwithstanding the close engagement, though, the partnership remained largely at the political and diplomatic level, with little progress on the economic and security front. With Prime Minister Narendra Modi injecting new vigor into India’s Act East policy, Vietnam has became central to India’s strategic calculus as one of the anchor countries of India’s policy in the region.

For India, the foundations for more robust strategic and security ties were laid during former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s visit to Vietnam in 2010. Further progress was made in September 2014, with the visit by President Pranab Mukherjee. Broadening the scope of the India-Vietnam partnership, during October 2014, Vietnam’s Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung paid a state visit to India and signed a joint statement affirming Vietnam as an important pillar of India’s foreign policy, while also concluding multiple memorandums. This evolving relationship is receiving a further boost from American policies towards Vietnam.

Laying the Groundwork

At a joint news conference, Carter and his Vietnamese counterpart General Phung Quang Thanh affirmed that both the countries are committed to deepening the defense relationship and laying the groundwork for the next 20 years of partnership. Both countries signed a Joint Vision Statement in which the United States pledged its support for Vietnamese peacekeeping training and operations as well as cooperation in search-and-rescue and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. The breakthrough opens the door to greater cooperation in the future.

The Joint Vision Statement follows Washington’s announcement last year that it would lift its ban on sales of weaponry to Vietnam. While the announcement did limit arms sales to equipment that will help Vietnam improve its maritime security, the move highlights America’s realist policies of bolstering the capabilities of countries in the region. Amid heightened tensions over China’s expanding land reclamation and militarization, senior Republican Senator John McCain has argued that America needs to provide Vietnam with more defensive weapons. These statements and overtures reflect a marked change from America’s traditional policies toward Vietnam, thereby underlining the geopolitical shifts of the 21st century.

These shifts in America’s East Asia policy serve India’s Act East policy well. Revamped U.S. ties with Vietnam provide impetus to India’s own strategic partnership with Vietnam. On the other hand, Indo-U.S. cooperation in East Asia lends stimulus to the concept of the Indo-Pacific as a seamless strategic construct. Vietnam could possibly become the focal country in Indo-U.S. cooperation, as both New Delhi and Washington can benefit strategically. Meanwhile, the India-U.S. Defense Framework agreement should serve as a bedrock that coalesces India’s future engagements in the region.

Quadrilateral Challenges

In contrast to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – which saw only a very modest commitment from Australia and Japan – Indo-U.S. co-operation in the region is a realistic proposition with a clear alignment of foreign and defense policies. The U.S. is strategically and commercially invested in the modernization of India’s defense industry, bolstering India’s preparedness. On the other hand, even though India’s trade relationship with Japan is strong, and ties with Australia are growing, little headway has been made in the area of defense co-operation with either country. Instead, New Delhi’s relations with these two important Asia-Pacific countries has remained mostly political and diplomatic.

Japan’s offer to sell the amphibious sea planes in the form of the ShinMaywa US-2 reflects its reluctance to share critical technologies. India’s interest in the Japanese built Soryu-class submarines has been one-sided and has received little reciprocation so far. For defense co-operation to progress on the envisaged lines of militarily balancing China, this co-operation will need to progress beyond sporadic bilateral military exercises to the point where Japan is ready to share defense technology with its allies. Military and political posturing without deeper cooperation in the field of defense is of little benefit to India. Australia, on the other hand, has little to offer materially and is also constrained by the limited size of its military. However, Australia’s experience in operating with other militaries in the region is something India can benefit from. Given that bilateral defense cooperation in the region has yet to gain momentum, Indo-U.S. defense co-operation will be important in creating extended links to balance China’s growing military might.

Synchronizing Cooperation

India needs to extend more credit to Vietnam: $100 million is modest given the role it expects Vietnam to play within the Asia-Pacific context. Although it is encouraging that India is proactively reaching out to build ties with Vietnam, the scale and speed of engagement is disappointing. The supply of four off-shore patrol vessels is the highlight of the defense co-operation kick initiated last year. Yet Vietnam’s acquisition of Russian Kilo-class submarines and Sukhoi aircraft presents opportunities for India to provide training on platforms it has been using for years. The sale of the Indo-Russian supersonic Brahmos missile is another avenue that can be explored to bolster Vietnamese defense capabilities in the South China Sea.

It is also important for the United States to strengthen existing bilateral security frameworks to bolster the capabilities of regional powers. American endorsement of security cooperation between Japan and the Philippines in conjunction with a defense framework agreement and efforts to bolster Vietnam’s maritime capabilities are steps that will help institutionalize an architecture that can maintain balance in disputed areas. The India-U.S. Joint Vision and the mention of the South China Sea is India’s strategic response to the growing Chinese naval profile in the Indian Ocean Region. In this context, America’s outreach to Vietnam and India’s Act East policy are symbolic of India-U.S. cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.

Sylvia Mishra and Pushan Das are researchers at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.