Eight years ago, the late K. Subrahmanyam, one of India’s leading strategic thinkers, began one of his many book chapters with a quote from George W. Bush on the U.S.-India nuclear deal at a press briefing in March 2006. “What this agreement says is things change, times change, that leadership can make a difference,” Bush said at the time.

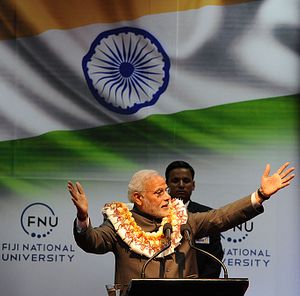

Even if most of us accept Bush’s general premise, few – perhaps even Subrahmanyam himself – could have foreseen the burst of activity and pace of change in Indian foreign policy that Prime Minister Narendra Modi has ushered since his election last year.

Modi has now visited over 20 countries in an official capacity, unprecedented for any Indian prime minister in so short a time. Apart from the miles he has clocked, the inroads he has made thus far have also been impressive – from revitalizing India’s ties with smaller states in its immediate neighborhood to engaging the world’s major powers (See: “What’s Next for US-India Defense Ties with Obama’s Trip?”). A land boundary agreement with Bangladesh, an energized U.S.-India relationship, and rescue and post-disaster operations in Yemen and Nepal respectively are just some of the initiatives that have that we have seen thus far.

Yet even as these developments have been afoot, experts have been debating exactly how much continuity and change there is in Modi’s foreign policy relative to his predecessors. The topic recently took center stage at the launch of a new book by C Raja Mohan – one of India’s most internationally recognized strategic thinkers – at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi.

During the event, Indian Foreign Secretary S. Jaishankar, Subrahmanyam’s son and a close friend of Raja Mohan, made arguably the clearest and most concise case that the Modi government was pursuing a new ‘proactive’ foreign policy (See: “India Needs a More Ambitious Foreign Policy, Says Country’s Top Diplomat“). In terms of content, Jaishankar noted that, among other things, a reasonable but at times firm neighborhood first policy, the forward momentum on the nuclear deal with the United States, and a coherent Indian Ocean strategy now in the works were all examples of changes from the previous government led by Manmohan Singh.

“So let me ask you: does this look like diplomacy as usual?” Jaishankar said.

To some, Indian foreign policy under Modi does indeed look a little more familiar than the picture Jaishankar painted. Indeed, before Jaishankar spoke, Shashi Tharoor, currently chairman of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on External Affairs and a member of parliament with the opposing Congress Party, noted that several of the initiatives under the Modi government were ones that Congress had earlier pushed when it had power but the BJP had thwarted. These included the land boundary agreement and the nuclear deal.

Of course, this dynamic is an all-too-familiar one hardly limited to just Indian politics. And indeed, Jaishankar himself, to his credit, conceded that while some of these were new developments, others were “decisive conclusions to an otherwise unfinished national agenda.”

But beyond the content of Indian foreign policy, Jaishankar seemed to suggest that the bigger shifts were in how India was conducting itself on the world stage and the tools of statecraft it was using in this process. In terms of conduct, Jaishankar seemed to suggest that India’s added confidence and larger footprint was indicative of a new proactive foreign policy in the works focused on actively shaping and driving events as opposed to just reacting to them; on being active and nimble rather than neutral and risk-averse.

What exactly is this proactive foreign policy? Though he did not explicitly define it, he said it was based on a clear sense of its priorities, an integrated view of regions, and a more vigorous effort directed at confidently pursuing multiple relationships simultaneously and making a global impact. This was in contrast to a more reactive approach which sought a lower profile and adopted a more siloed approach, often associated with the country’s tradition of non-alignment.

Jaishankar then went on to a more detailed list of five “innovations” in the way India was using the tools of statecraft to further this proactive foreign policy – narratives; lexicon and imagery; soft power; the Indian diaspora; and the link between foreign policy and national development. First, the Modi government was developing a narrative as part of a transition to making India a leading power. For instance, Jaishankar said, attention to India’s sacrifices in WWI, or its record in peacekeeping operations, strengthens its position for a permanent seat in the UN Security Council.

Second, the creation of a new lexicon and imagery – whether it is from a “Look East” to “Act East” policy or the image of a “first responder” in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief – has been critical in signaling and driving foreign policy change (See: “Modi Unveils India’s Act East Policy to ASEAN in Myanmar”). Third, the Modi government has emphasized the use of soft power in Indian foreign policy, as evidenced by the International Day of Yoga and its links with the country’s culture and heritage.

The fourth “innovation” is related to the Indian diaspora. While their achievements have long been broadly appreciated, the Modi government has been more direct thus far in engaging with overseas Indians, as evidenced by the turnout at Madison Square Garden during his visit to the United States earlier this year. Fifth and finally, there has also been a more explicit link made between diplomacy and national development efforts, with India working hard to leverage its international relationships to bring resources, technology and best practices to further its own development such as through the Make in India initiative.

Here too, one can quibble with how innovative each of these individual points is. For instance, Modi is far from the first Indian premier to speak about the link between foreign policy and economic development. But taken together and seen as part of Modi’s overall foreign policy approach, once can indeed see the outlines of something quite new as Jaishankar suggested.

Of course, this is not to suggest that Indian foreign policy under Modi has not encountered its fair share of challenges thus far in Modi’s first year. On some fronts, New Delhi has been a little too ‘proactive,’ as with its unilateral incursion into Myanmar in a cross-border raid (See: “The Truth About India’s Militant Strike in Myanmar”). India’s Pakistan policy has also at times seemed more rudderless than resolute. Though the Modi government is hardly the only one to struggle with India-Pakistan relations, that also dents the case for change and the advent of a reasonable but firm neighborhood first policy.

Challenges could also lie ahead, especially since this is just Modi’s second year in office. Shyam Saran, India’s respected former foreign secretary, said that while he saw promise in Modi’s active foreign policy, he was also worried about the capacity of the Indian government to implement the many commitments it had made. “We need to really put the accent now on the nuts and bolts of how to get foreign policy actually implemented,” he said.